1906

COVID-19 olfactory rehabilitation assessment through fMRI and VBM1GE Healthcare, Madrid, Spain, 2University Rey Juan Carlos, Móstoles, Spain, 3Hospital Quironsalud Madrid, Pozuelo de Alarcón, Spain, 4Hospital Universitario Fundación Alcorcón, Alcorcón, Spain

Synopsis

Keywords: Infectious disease, COVID-19, Anosmia

Olfactory fMRI has provided an objective assessment of olfactory function in normal brain and pathological subjects. Optimizing the fMRI acquisition is of paramount importance when studying olfactory areas due to high B0 inhomogeneities and thin cortical areas involved. Fully synchronizing the acquisition to the odorants delivery with patient respiration increases the effectiveness of the experiment. Using this technique in COVID-19 patients with anosmia could determine the correct rehabilitation therapy for these subjects and new treatment pathways.

Introduction

Review studies1 have shown that at least 50% of COVID-19 patients are showing sudden olfactory loss, also known as anosmia. In comparison with other respiratory infectious diseases it is estimated that 20% of COVID-19 patients show olfactory alterations as a sequel.It is still unclear the underlaying mechanisms that trigger anosmia in patients suffering from COVID-19 but several hypothesis suggest olfactory cleft syndrome, local inflammation in the nasal epithelium, early apoptosis of olfactory cells, changes in olfactory cilia and odor transmission, damage to microglial cells, effect on olfactory bulbs, epithelial olfactory injury, and impairment of olfactory neurons and stem cells.

The ongoing prevalence of COVID-19 justifies the need for exploring the most effective treatment and rehabilitation care pathways. In this sense, the cognitive process in olfactory rehabilitation targets the creation of new olfactory cerebral pathways thanks to the brain neuroplasticity, therefore focusing on working on the cognitive, physiological and emotional features of the olfactory process.

Usually the olfactory is assesed by the Connecticut Chemosensorial Clinical Research Centre test2. This test present to the patient several dilutions which need to be scored subjectively accordingly to threshold activation and odorant identification.

In this sense, we explore in this work the use of fully synchronized olfactory functional MRI3,4 to objectively assess the physiological activation of the olfactory system and related areas after a rehabilitation therapy, which could determine the treatment effetiveness and drug development.

Methods

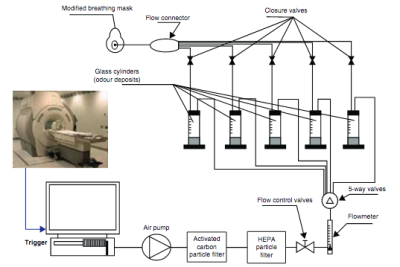

As part of an IRB approved study, MRI data of 4 female patients ranged 45-54y, who presented persistent olfactory loss after COVID-19 infection, underwent a targeted olfactory rehabilitation therapy of 10 sessions during 2.5 months.Patients were scanned prior to the start of the therapy and after the end of the therapy. Images were acquired on a 3T Signa Premier (GE Healthcare, Waukesha, United States) at Hospital Quirónsalud (Madrid, Spain) after obtaining written informed consent. The MRI protocol used a dedicated 48-channel AIRTM head coil and comprised conventional 3D-T1-MPRAGE (1mm iso-voxel), CUBE T2-FLAIR and DTI sequences. In addition, a 10 minute fMRI study fully synchronized with the scanner trigger and respiratory belt delivered two different odors (mint and vanilla) randomized in an event-related fashion within the duration of the study (Fig.1). fMRI acquisition parameters were TR=1s, TE=20.6ms, FOV=22cm, Acquisiton matrix=96x96, flip angle=62, HyperBand factor=3, ASSET factor=2, voxel size 2.3mm iso, pixel bandwidth=3906Hz.

SPM12 was used to segment the structural MPRAGE T1 images and to realign, coregister and run a first and second analysis (paired t-test) on the fMRI images.

Results

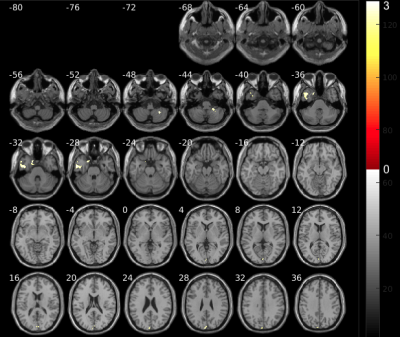

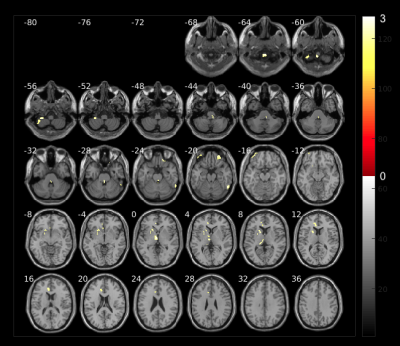

Fig. 2 shows increased volumes at the beginning of the therapy which belong to the first weeks after COVID-19 infection. The areas with higher volumes compared to 2.5 months later are: cerebellum, temporal lobe, parahippocampal region and cuneus. We hypothesize that these changes may be related to inflamatory processess due to virus infection as reported in other5,6.Volume changes in brain areas involved in the targeted olfactory rehabilitation are shown in Fig. 3, such as the fusiform gyrus, caudate and orbital gyrus7.

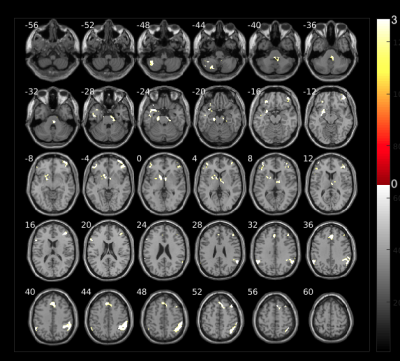

The olfactory rehabilitation therapy shows impact in the activation of several brain areas after odorant delivery (Fig. 4). The parahippocampal gyrus, frontal gyrus, amygdala, caudate, putamen and insula, show certain degree of improved activation and are regions involved in olfactory function which are mediated by parellel and hierarchical processing8.

Discussion

The small sample size for this study provides limited relevant results but points to an effective way of rehabilitation therapy in anosmic patients after COVID-19 infection and consistent results in subject-based olfactory fMRI experiments.Changes seen in volumetry could be caused by inflammatory processes that decline during the time of the rehabilitation with the counterpart of increased volumes in the areas targeted in the olfactory rehabilitation.

Functional changes are correlated with patient qualitative scores on rough odor discrimination and threshold activation, although more clinical cases would be desirable to be enrolled.

Conclusion

Bringing the olfactometer into fMRI provides robust synchronization and means of objective assessment of brain areas involved in olfaction such as the caudate nucleus, fusiform gyrus, parahippocampal gyrus, orbitofrontal gyrus and amygdala.The optimization of the fMRI acquisition in consonance with the olfactometer device opens a new clinical pathway to neurorehabilitation in anosmic patients and new fields in neuropsychology.

Acknowledgements

No acknowledgement found.References

[1] Najafloo R, Majidi J, Asghari A, et al. Mechanism of Anosmia Caused by Symptoms of COVID-19 and Emerging Treatments. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2021;12(20):3795-3805. doi:10.1021/acschemneuro.1c00477

[2] Cain, W. S., Goodspeed, R. B., Gent, J. F., & Leonard, G. (1988). Evaluation of olfactory dysfunction in the Connecticut chemosensory clinical research center. The Laryngoscope, 98(1), 83-88.

[3] Borromeo, S., Hernandez-Tamames, J. A., Luna, G., Machado, F., Malpica, N., & Toledano, A. (2010). Objective assessment of olfactory function using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI). IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement, 59(10), 2602-2608.

[4] Toledano, A., Borromeo, S., Luna, G., Molina, E., Solana, A. B., García-Polo, P., ... & Álvarez-linera, J. (2012). Estudio objetivo del olfato mediante resonancia magnética funcional. Acta Otorrinolaringológica Española, 63(4), 280-285.

[5] de Melo, G. D., Lazarini, F., Levallois, S., Hautefort, C., Michel, V., Larrous, F., ... & Lledo, P. M. (2021). COVID-19–related anosmia is associated with viral persistence and inflammation in human olfactory epithelium and brain infection in hamsters. Science translational medicine, 13(596), eabf8396.

[6] Benedetti, F., Palladini, M., Paolini, M., Melloni, E., Vai, B., De Lorenzo, R., ... & Mazza, M. G. (2021). Brain correlates of depression, post-traumatic distress, and inflammatory biomarkers in COVID-19 survivors: A multimodal magnetic resonance imaging study. Brain, behavior, & immunity-health, 18, 100387.

[7] De Araujo, I. E., Rolls, E. T., Velazco, M. I., Margot, C., & Cayeux, I. (2005). Cognitive modulation of olfactory processing. Neuron, 46(4), 671-679.

[8] Savic, I., Gulyas, B., Larsson, M., & Roland, P. (2000). Olfactory functions are mediated by parallel and hierarchical processing. Neuron, 26(3), 735-745.

Figures

Fig.1 MRI compatible olfactometer device. The system is fully synchronized with the fMRI acquisition and the olfactometer triggers up to 8 electro valves that deliver the selected odorants. Finally the air flow with the mixed odorants is delivered to the patient through an oxygen mask.