1905

Blood-brain barrier breakdown in COVID-19 ICU survivors: a preliminary study1Department of Biomedical Engineering, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, United States, 2Department of Radiology, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, United States, 3Department of Surgery, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, United States, 4Department of Medicine, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, United States, 5Department of Neurology, Neurosurgery, Surgery, Anesthesiology, and Critical Care Medicine, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Infectious disease, COVID-19

COVID-19 affects multiple organ systems in the acute phase, however, limited knowledge is known about the long-term impact on the brain following COVID-19 pneumonia, especially for those severe COVID-19 ICU survivors. Here, we used a water-extraction-with-phase-contrast-arterial-spin-tagging (WEPCAST) MRI which can non-invasively measure BBB permeability to water. The results showed significantly higher permeability-surface-area product (PS) in COVID-19 ICU survivors, which provided preliminary evidence that there was a BBB breakdown in COVID-19 ICU survivors at 4 months after initial infection.Introduction

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) induced by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) has caused an unprecedented health crisis and increased morbidity and mortality1. Despite the extensive characterization of COVID-19 in the acute phase, the long-term impact of COVID-19 pneumonia on the brain is poorly understood2, especially for those who survived the intensive care unit (ICU) hospitalization. Prior studies reported that severe COVID-19 infection resulted in long-term neurocognitive deficits3,4, including brain fog5, cognitive decline6, and other psychiatric disorders7,8, suggesting damage to the brain. Particularly, neuroinflammation is thought to be a major contributor to brain abnormalities in long-COVID, yet blood-based biomarkers are likely contaminated by systemic inflammations from COVID-19 pneumonia and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), and thus, lack specificity. Blood-brain barrier (BBB) breakdown, however, is a known hallmark of neuroinflammation and may represent a more favorable alternative. Recently, a novel technique, referred to as water-extraction-with-phase-contrast-arterial-spin-tagging (WEPCAST) MRI, was developed to non-invasively measure BBB permeability to water, without requiring exogenous (gadolinium) contrast agents9,10. Herein, we used WEPCAST MRI to assess BBB integrity in COVID-19 ICU survivors at approximately 4 months after their initial infection. Correlations between neurophysiological measures were also evaluated.Methods

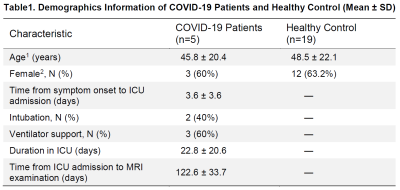

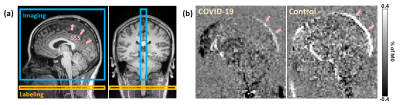

Participants: 5 COVID-19 ICU survivors (45.8±20.4 yrs, 2M/3F, duration of ICU stay= 22.8±20.6 days) and 19 age- and sex-matched healthy controls (48.5±22.1 yrs, 7M/12F) were recruited under IRB approval. The COVID-19 survivors were scanned at approximately 4 months after their initial COVID-19 infection. Detailed demographic information of the participants is summarized in Table 1.Experiment: All MRI scans were conducted on a Siemens 3T Prisma scanner (Siemens Healthineers, Erlangen, Germany) using a 32-channel head coil. The WEPCAST technique probes BBB permeability to water by labeling the water molecules in the incoming arteries and, by determining the fraction of the water that remained in the vessel versus those exchanged into the brain tissue at the capillary-tissue interface, one can obtain an estimation of the water extraction fraction (E). The measurement is typically performed in the major draining vein of the brain, e.g., superior sagittal sinus (SSS), yielding a whole-brain measure of $$$E$$$. Representative imaging and labeling positions are shown in Figure 1a. Additionally, global cerebral blood flow (CBF), $$$f$$$, is obtained by phase contrast (PC) velocity MRI and normalized by whole-brain volume as measured on T1-MPRAGE11. Finally, the BBB permeability index, referred to as permeability-surface-area product (PS), can be calculated from $$$E$$$ and $$$f$$$ according to the Renkin-Crone Model: $$$PS=-ln(1-E)\cdot f$$$

Imaging parameters: WEPCAST MRI9,10 was performed with the following parameters: TR/TE=9200/9.5ms, FOV=200×200mm2, voxel size=3.1×3.1×10mm3, labeling duration=4000ms, post-labeling delay=3000ms, VENC=20cm/s, GRAPPA=3. PC velocity MRI was performed with the following parameters: TR/TE=25/8ms, FOV=200×200mm2, voxel size=0.5×0.5×5mm3, VENC=60cm/s.

Statistical analysis: CBF, E and PS values between the COVID-19 ICU survivors and healthy controls were compared using linear regression in which the group assignment was the independent variable, and age and sex were covariates. The association between CBF and E was also evaluated by linear regression.

Results

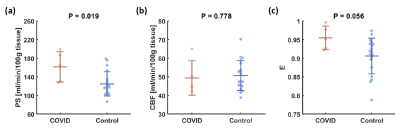

Figure 1b shows representative WEPCAST images in a COVID-19 ICU survivor (72 yrs, M) and healthy control (75 yrs, M). It can be observed that the WEPCAST signal in the COVID-19 ICU survivor (arrows) is lower than that of the control.Quantitative comparison of BBB permeability is shown in Figure 2a. PS is significantly higher in COVID-19 ICU survivors when compared to healthy controls (p = 0.019). In contrast, there was no significant difference in CBF between the groups (p = 0.778, Figure 2b). Since PS was calculated from CBF and E, when CBF has no group difference, it is expected that E would show a difference. Indeed, we found that COVID-19 ICU survivors had a larger E (p = 0.056, Figure 2c) when compared to the control group.

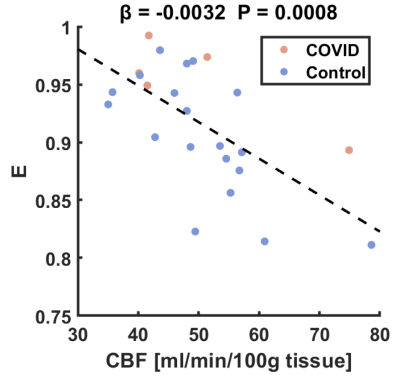

To further elucidate the reason that PS had a greater sensitivity than E in detecting the group differences, we studied the relationship between CBF and E. Figure 3 displays the scatter plot between CBF and E in which a significant inverse relationship was observed ($$$β$$$ = -0.0032, p = 0.0008). Therefore, it appears that CBF and E both contained physiological noises (normal variation) that are correlated with each other, and when computing PS. These noises/variations were reduced/canceled out and resulted in high sensitivity in detecting subtle BBB breakdown using PS.

Discussion and conclusion

The present study used a noninvasive WEPCAST MRI technique to measure whole-brain BBB permeability to water in COVID-19 ICU survivors. A higher PS value was observed, suggesting a BBB breakdown in severe COVID-19 ARDS patients. These findings are consistent with the notion of neuroinflammation secondary to SARS-CoV-2 infection4,12.Since CBF was not different between COVID-19 patients and healthy controls, measurement of E should be sufficient to prove BBB disruption in COVID-19 patients. However, based on the observation in Figure 3, we speculate that the additional measure of CBF could allow higher sensitivity in detecting abnormal BBB permeability.

In summary, this study provided preliminary evidence that there was a BBB breakdown in COVID-19 ICU survivors at 4 months after initial infection, suggesting a long-term adverse effect of COVID-19 on the brain.

Acknowledgements

No acknowledgement found.References

1. Dong E, Du H, Gardner L. An interactive web-based dashboard to track COVID-19 in real time. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2020;20(5):533–534.

2. Nalbandian A, Sehgal K, Gupta A, et al. Post-acute COVID-19 syndrome. Nat. Med. 2021;27(4):601–615.

3. Helms J, Kremer S, Merdji H, et al. Neurologic features in severe SARS-CoV-2 infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382(23):2268–2270.

4. Romero-Sánchez CM, Díaz-Maroto I, Fernández-Díaz E, et al. Neurologic manifestations in hospitalized patients with COVID-19: The ALBACOVID registry. Neurology 2020;95(8):E1060–E1070.

5. Hugon J, Msika E-F, Queneau M, Farid K, Paquet C. Long COVID: cognitive complaints (brain fog) and dysfunction of the cingulate cortex. J. Neurol. 2022;269(1):44–46.

6. Douaud G, Lee S, Alfaro-Almagro F, et al. SARS-CoV-2 is associated with changes in brain structure in UK Biobank. Nature 2022;604(7907):697–707.

7. Huang L, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Gu X. 6-month consequences of COVID-19 in patients discharged from hospital: a cohort study. Lancet 2021;397(10270):220–232.

8. Premraj L, Kannapadi N V, Briggs J, et al. Mid and long-term neurological and neuropsychiatric manifestations of post-COVID-19 syndrome: A meta-analysis. J. Neurol. Sci. 2022;434:120162.

9. Lin Z, Li Y, Su P, et al. Non-contrast MR imaging of blood-brain barrier permeability to water. Magn. Reson. Med. 2018;80(4):1507–1520.

10. Lin Z, Jiang D, Liu D, et al. Noncontrast assessment of blood–brain barrier permeability to water: Shorter acquisition, test–retest reproducibility, and comparison with contrast-based method. Magn. Reson. Med. 2021;86(1):143–156.

11. Aslan S, Xu F, Wang PL, et al. Estimation of labeling efficiency in pseudocontinuous arterial spin labeling. Magn. Reson. Med. 2010;63(3):765–771.

12. Alexopoulos H, Magira E, Bitzogli K, et al. Anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in the CSF, blood-brain barrier dysfunction, and neurological outcome: Studies in 8 stuporous and comatose patients. Neurol. Neuroimmunol. neuroinflammation 2020;7(6):4–8.

Figures