1890

Unsupervised Domain Adaptation for Automated Knee Osteoarthritis Phenotype Classification1CU Lab for AI in Radiology (CLAIR), Department of Imaging and Interventional Radiology, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Sha Tin, NT, Hong Kong, 2Department of Imaging and Interventional Radiology, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Sha Tin, NT, Hong Kong, 3Department of Radiology, Shanghai Sixth People's Hospital Affiliated to Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine, Shanghai, China, 4Centre for Clinical Research and Biostatistics, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Sha Tin, NT, Hong Kong, 5Department of Orthopaedics & Traumatology, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Sha Tin, NT, Hong Kong

Synopsis

Keywords: Osteoarthritis, Osteoarthritis

We propose a knee osteoarthritis phenotype classification system using unsupervised domain adaptation (UDA). A convolutional neural network was initially trained on a large source dataset (Osteoarthritis Initiative, n=3116), then adapted to a small target dataset (n=50). We observed a significant performance improvement compared to the classifiers trained solely on the target dataset. We demonstrated the feasibility of applying UDA for medical image analysis in a small label-free dataset.

Introduction

Knee osteoarthritis (OA) is one of the most prevalent degenerative diseases. The ageing population brings an increasing need for knee OA diagnostics and treatment1. Assessment of knee OA based on manual grading of MRI outcomes is labor-intensive. Deep learning methods have been developed to automate the grading of knee injuries, including knee OA2–4. Those works require large datasets with high-quality labels, which is often difficult to obtain. To address this challenge, in this work, we explored the application of unsupervised domain adaptation (UDA) in knee OA phenotype classification, which adapted the model trained on a large dataset to a small label-free dataset. Our experiments show the proposed application achieved a satisfactory classification performance.Data

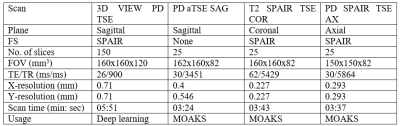

Two datasets are involved in this retrospective study. The source dataset (n=3,116) was collected from the Osteoarthritis Initiative (OAI) dataset. Each source sample contains a 3D double echo steady state (DESS) MRI5 and a set of MRI osteoarthritis knee scores (MOAKS)6. The target dataset (n=50) was collected at the Prince of Wales Hospital (Sha Tin, New Territories, HKSAR) in 2020-2021. Our institutional review board approved the study. Each target sample contains a 3D turbo/fast spin echo (TSE/FSE) MRI and a set of MOAKS scores prepared by two experienced radiologists (D.G.C. and F.X, Intraclass Correlation Coefficient=0.999, p<0.01). The detailed demographic for both datasets and the MRI acquisition protocol for the target dataset are available in Figures 1 and 2.We further converted the MOAKS scores to binary knee OA phenotype defined in Roemer et al.7. The cartilage/meniscus phenotype is characterised by damages in meniscus, medial and lateral cartilage. The subchondral bone phenotype is characterised by bone marrow lesions. We randomly sampled the source dataset to address the severe class imbalance, keeping one-third of the samples positive. The balanced source dataset (Figure 1) was used for source encoder training.

Methods

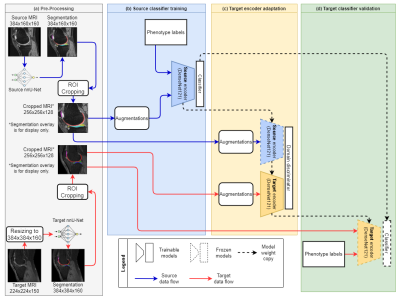

We adopted the adversarial discriminative domain adaptation (ADDA)8 framework in this study. Figure 3 gives an overview of our four-step UDA pipeline. We first performed pre-processing for the source and target datasets. Specifically, we aligned the input image sizes of both datasets, then segmented the knee cartilages and meniscus using nnU-Net9. The auto-segmentation masks guide the region of interest (ROI) cropping. The ROI covered the tibiofemoral joint (TFJ) and patellofemoral joint (PFJ) of each sample. Then, we pre-trained the feature encoder. A 3D DenseNet 12110 source encoder with an attached classification head was trained on the balanced source dataset. This source classifier was optimised by focal loss11 (gamma=1) and Adam12 optimiser (learning rate=10-6, weight decay=10-3) with a batch size of 2.Further, the pre-trained source encoder was copied to initialise the target encoder and ready to be adapted to the target dataset. The adaptation involves a fixed-parameter source encoder, a domain discriminator, and a trainable target encoder. This adversarial adaptation is optimised by domain adversarial loss13 and stochastic gradient descent (SGD)14 optimiser (learning rate=0.001, momentum=0.9, weight decay=10-3) with a batch size of 2. We decay the learning rate by the below formula,

$$\alpha_{n+1} = \alpha_n \times (1 + \gamma \times n)^{-\lambda}$$

where $$$\alpha_{n+1}$$$ and $$$\alpha_n$$$ are the learning rates at the next and the current epoch, $$$n$$$ is the current epoch count, and $$$\gamma$$$ and $$$\lambda$$$ are hyperparameters set at 0.0003 and 0.75, respectively.

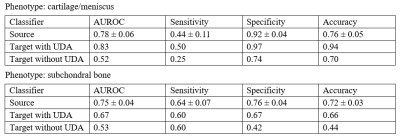

We evaluated the source classifier on a 20% hold-out test set with a 100-time bootstrapping. As for the target classifiers, we leveraged a leave-one-out strategy. During target encoder adaptation, we continuously fed source samples while looping the target samples. We evaluate the models by metrics including area under receiver operating characteristic curve, sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy. For comparison, we trained a non-UDA classifier on the target dataset via supervised learning. A McNemar test was used to compare the performance of classifiers on the target dataset. We consider a statistical significance when p < 0.05.

Results

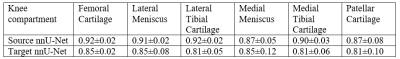

In pre-processing, we trained two nnU-Net segmentation models by the official implementation with the default settings for the source and target datasets. Two nnU-Nets gave the dice similarity coefficients (DSC) ranging from 0.81 to 0.92 among source and target datasets on six knee compartments. A table with full DSC results is shown in Figure 4. The classification performance of the source classifiers, target classifiers and the non-UDA classifiers is available in Figure 5. The McNemar test between target classifiers trained with or without UDA has a p-value of 0.013 and 0.027 for the cartilage/meniscus and subchondral bone phenotypes. Both outcomes were significant, showing that UDA improved the knee OA phenotype classification performance on the small target dataset.Conclusion

In conclusion, we proposed a novel application of UDA for transferring knowledge of knee OA phenotype classification obtained from a large source dataset to a small label-free target dataset. We demonstrated the proposed work using the large OAI dataset (n=3,116) as the source dataset and our local dataset (n=50) as the target dataset. This approach may provide a useful tool for AI-based knee OA assessment when high quality training data is unavailable.Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge Ben Chi Yin Choi and Cherry Cheuk Nam Cheng for assistance in patient recruitment and MRI exams. This study was supported by a grant from the Innovation and Technology Commission of the Hong Kong SAR (Project MRP/001/18X), and a grant from the Faculty Innovation Award, The Chinese University of Hong Kong.

References

1.James SL, Abate D, Abate KH, et al. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. The Lancet. 2018;392(10159):1789-1858. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32279-7Figures