1882

Semi-Supervised Learning with Spatial Pseudo Labeling for Peritumoral Infiltration Prediction in Glioblastoma using MR Fingerprinting1Department of Biomedical Engineering, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, OH, United States, 2Department of Quantitative Health Sciences, Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, OH, United States, 3Department of Radiology, Case Western Reserve University and University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center, Cleveland, OH, United States, 4Center for Biomedical Image Computing and Analytics, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, United States, 5Department of Radiology, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, United States, 6Department of Pathology, Case Western Reserve University and University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center, Cleveland, OH, United States, 7Department of Neurosurgery, Case Western Reserve University and University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center, Cleveland, OH, United States, 8Seidman Cancer Center and Case Comprehensive Cancer Center, Cleveland, OH, United States, 9Piedmont Health, Atlanta, GA, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Machine Learning/Artificial Intelligence, Cancer

Existing glioblastoma (GB) infiltration models are often limited by lack of true infiltration labels and employ the assumption that edema closer to tumor has higher infiltrative potential relative to distant edema. Here, we propose a semi-supervised learning scheme that incorporates pretraining on the near-far heuristic and spatial pseudo labeling using true infiltration labels for voxel-wise tumor infiltration prediction. Our results show improved classification performance following finetuning on labeled infiltration data compared to training on the near-far heuristic alone and indicate the potential in employing MR fingerprinting-based models to guide GB diagnosis and treatment.Introduction

Glioblastoma (GB) recurrence is inevitable, due in part to failure of standard magnetic resonance (MR) imaging to definitively identify infiltration into the peritumoral non-enhancing region which thus remains unresectable1. Unfortunately, existing GB infiltration prediction models are often limited by lack of true infiltration labels2,3 and instead utilize the heuristic that edema closer to the tumor has higher infiltrative potential compared to distant edema. This is largely due to the challenges of acquiring pathologically confirmed image references. Here, we hypothesize that integrating the near-far heuristic model with true infiltration labeled data will fully utilize available imaging data to ultimately improve prediction performance. By leveraging data from a cohort of patients with pathologically confirmed sites of peritumoral infiltration, we integrate pretraining based on the near-far heuristic and spatial pseudo labeling4 to develop a semi-supervised MR fingerprinting (MRF)-based model for voxel-wise tumor infiltration prediction.Methods

Study DesignPre-operative MRF (M0, T1 and T2) and multiparametric MRI (mpMRI; T1w, T2w, T1w-Gd, FLAIR, and ADC) from GB patients (n = 25) were analyzed. A select number (n = 10) of subjects had pathologically confirmed sites of non-enhancing peritumoral infiltration identified by either targeted biopsy or intra-operative 5-ALA fluorescence-guided resection5. Subject data was obtained from an institutional review board (IRB) approved study.

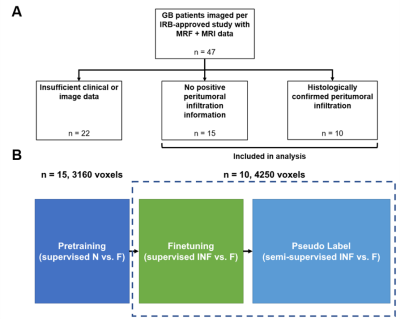

To utilize our dataset (Figure 1A) of subjects without positive infiltration data (unlabeled) and infiltration exemplars (labeled), a two-stage study design was adopted (Figure 1B) where the near-heuristic was used for initial supervised learning and infiltration data was incorporated for semi-supervised model finetuning.

In the absence of infiltration ground truth, prior studies2,3 used the fact that edema closer to the tumor (NEAR) has higher infiltration compared to distant edema (FAR). We adapted this heuristic to pretrain a feedforward network to classify NEAR and FAR voxels using data from unlabeled subjects (n = 15). The model was then finetuned to distinguish between true infiltration (INF) and FAR voxels using data from infiltration subjects (n = 10). Finally, we pseudo labeled in a spatial manner by iteratively incorporating edema voxels adjacent to confirmed INF voxels.

Image Preprocessing and Tumor Segmentation

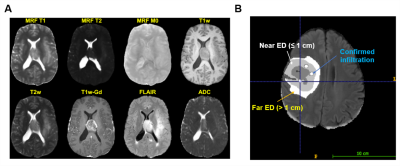

Multiparametric MRI were registered to the SRI24 atlas, skull stripped, bias corrected6, and z-score normalized (Figure 2A). ADC and MRF maps were skull stripped and registered to the SRI24 atlas; ADC was also bias corrected.

Tumors were segmented using DeepMedic7 into necrotic, enhancing tumor, and edema ROIs prior to manual annotation (Figure 2B).

For all subjects (n = 25), two edema ROIs were defined on pre-operative FLAIR by a radiology resident (CT) and reviewed by a board-certified, fellowship-trained neuroradiologist (CB): a “near” ROI (NEAR) adjacent to the enhancing tumor margin, and a “far” ROI (FAR) located further than 3 cm from the enhancing tumor margin2. For subjects with pathologically confirmed infiltration (n = 10), infiltration ROIs (n = 40) identified by targeted biopsy or intra-operative 5-ALA fluorescence-guided resection were annotated by a board-certified, fellowship-trained neuroradiologist (CB), reviewed in collaboration with the operating neurosurgeon (AES), and labeled as “infiltration” (INF).

Model Development

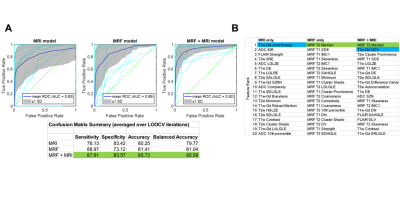

During pretraining (Figure 3A), voxel-based features (99 per image) were extracted from each image’s NEAR and FAR voxels (1549 near voxels, 1611 far) using a 3D 5x5x5 voxel sliding kernel. Following feature selection using minimum redundancy maximum relevance (MRMR)8, three models were developed: 1) MRF; 2) mpMRI; and 3) combined.

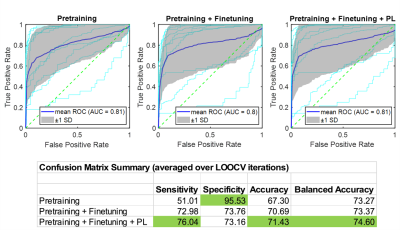

Finetuning was performed by training the model on INF and FAR voxel features from infiltration data (40 ROIs, 2593 voxels). Surface network layers were retained from pretraining with weights frozen, while deep layers were retrained on the INF-FAR problem (Figure 3B). Three iterations of spatial pseudo labeling were performed to incorporate unlabeled edema voxels (25787 total) adjacent to infiltration and far ROIs (Figure 3C).

Results

Pretraining with the Near-Far HeuristicPretraining performance was evaluated using leave-one-out-cross-validation (LOOCV), with the combined model achieving the best classification performance (Figure 4A; AUC = 0.92, bACC = 86.6%). MRMR feature selection identified MRF T2 features as having greatest significance in NEAR-FAR classification, followed by T1w-Gd features (Figure 4B). Specifically, MRF T2 intensity (median) was the most discriminating feature, an observation that was not repeated for T2w intensity in either mpMRI or combined models, indicating greater sensitivity of MRF relaxometry values.

Finetuning and Pseudo Labeling Using Infiltration Data

The combined pretrained model was finetuned (Figure 5) on infiltration data , resulting in LOOCV improvements to sensitivity (51% to 73%) and accuracy (67% to 70%). Following three iterations of spatial pseudo labeling, sensitivity (73% to 76%) and bACC (73% to 74%) were further improved.

We show pretraining using the near-far heuristic generates a model that is highly specific in distinguishing between regions of high and low infiltration potential but has reduced classification accuracy when applied to true infiltration prediction. By finetuning the model on subject exemplars with ground truth infiltration data and incorporating unlabeled edema through spatial pseudo labeling, our model achieves an appreciable increase in sensitivity and overall accuracy.

Conclusion

We introduce a semi-supervised learning scheme to improve GB infiltration prediction using infiltration MRF data and report improved classification following model finetuning and spatial pseudo labeling. These findings indicate the potential in employing MRF-based models to guide GB diagnosis and treatment.Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Siemens Healthineers, NIH grants R01 NS109439, T32 EB007509, T32 GM007250, and TL1 TR000441, the Clinical and Translational Science Collaborative (CTSC) of Cleveland, the Clinical and Translational Science Award (CTSA) grant UL1TR002548, and the Peter D. Cristal Chair of Neurosurgical Oncology (AES).References

1. Pekmezci M, Morshed RA, Chunduru P, et al. Detection of glioma infiltration at the tumor margin using quantitative stimulated Raman scattering histology. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):12162. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-91648-8

2. Rathore S, Akbari H, Doshi J, et al. Radiomic signature of infiltration in peritumoral edema predicts subsequent recurrence in glioblastoma: implications for personalized radiotherapy planning. J Med Imaging Bellingham Wash. 2018;5(2):021219. doi:10.1117/1.JMI.5.2.021219

3. Akbari H, Macyszyn L, Da X, et al. Imaging Surrogates of Infiltration Obtained Via Multiparametric Imaging Pattern Analysis Predict Subsequent Location of Recurrence of Glioblastoma. Neurosurgery. 2016;78(4):572-580. doi:10.1227/NEU.0000000000001202

4. Lee DH. Pseudo-Label : The Simple and Efficient Semi-Supervised Learning Method for Deep Neural Networks. ICML 2013 Workshop Chall Represent Learn WREPL. Published online July 10, 2013.

5. Chohan MO, Berger MS. 5-Aminolevulinic acid fluorescence guided surgery for recurrent high-grade gliomas. J Neurooncol. 2019;141(3):517-522. doi:10.1007/s11060-018-2956-8

6. Tustison NJ, Avants BB, Cook PA, et al. N4ITK: Improved N3 Bias Correction. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2010;29(6):1310-1320. doi:10.1109/TMI.2010.2046908

7. Kamnitsas K, Ledig C, Newcombe VFJ, et al. Efficient multi-scale 3D CNN with fully connected CRF for accurate brain lesion segmentation. Med Image Anal. 2017;36:61-78. doi:10.1016/j.media.2016.10.004

8. Peng H, Long F, Ding C. Feature selection based on mutual information criteria of max-dependency, max-relevance, and min-redundancy. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2005;27(8):1226-1238. doi:10.1109/TPAMI.2005.159

Figures