1880

Deep learning-based prognostic model using non-enhanced cardiac cine MRI in patients with heart failure.1Department of Radiology, Beijing Anzhen Hospital, Beijing, China, 2School of Biomedical Engineering, Sun Yat-Sen University, Guangzhou, China, 3National Heart and Lung Institute, Imperial College London, London, United Kingdom, 4Department of Cardiology, Beijing Anzhen Hospital, Beijing, China, 5Philips Healthcare, Beijing, China

Synopsis

Keywords: Machine Learning/Artificial Intelligence, Heart, Deep Learning; Heart Failure

We proposed a multi-source deep-learning model including traditional functional parameters and myocardial strain derived from cardiovascular magnetic resonance, as well as clinical features such as laboratory tests, electrocardiograms, and echocardiography. Meanwhile, we innovatively integrated cardiac motion characteristics through deep learning algorithms and fast neural convolution networks to construct deep learning heart failure prediction model. The results showed that compared with the traditional cox model, the deep learning model had higher efficacy for prognosis evaluation in patients with heart failure and could provide risk stratification in patients with heart failure, which may further guide clinical decision-making.Introduction

Heart failure (HF) is a global pandemic in healthcare, affecting more than 64 million people worldwide1,2,3. The prognosis prediction and risk stratification of HF can identify patients with a high risk and facilitate the application of robust clinical treatment strategies4. Conventional risk prediction models including clinical biomarkers and classical cardiac function parameters using cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) have been widely reviewed4,5,6. Artificial intelligence (AI) is being increasingly applied in various aspects of cardiovascular imaging7. However, current deep learning (DL) prediction models based on cardiovascular imaging modalities are limited to single-dimension parameters. To fully exploit the predictive potential of CMR in HF, the objective of this study is to build a new multi-source survival prediction model combined with a DL method and investigate the feasibility and accuracy of HF prediction for the performance of this model.Methods

503 patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF, in which LVEF is ≤40%) who underwent cardiac magnetic resonance between January 2015 and April 2020, were retrospectively included in this study. Patients with congenital heart diseases, infiltration myocardiopathy (e.g., amyloidosis and sarcoidosis), atrial fibrillation, acute myocardial infarction within 1 month were excluded.Baseline electronic health record data, including clinical demographic information, laboratory data, and electrocardiographic information were collected. The CMR study was performed using two different 3T magnetic resonance imaging systems (Ingenia CX; Philips Healthcare, Best, the Netherlands; or MR750w, General Electric Healthcare, Waukesha, Wisconsin, USA) with retrospective ECG and respiratory gate. Short axis non-contrast cine images of the whole heart were acquired to estimate the cardiac function parameters and the motion features of the left ventricle. Both cine images derived from two different MRI systems were based on a balanced steady-state free protocol covering bi-ventricle in short- and long-axes from the base to the apex.

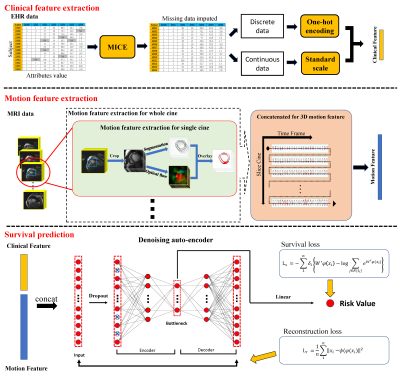

DL model used multi-source data, including heart motion information and clinical information and mapped them to the same dimensional space by feature extraction methods. Based on the joint representation feature, a neural network was applied for survival prediction. In the training datasets, methods based on DL framework were applied for denoising autoencoder (DAE) survival prediction. A few popular survival methods based on EHR data were simultaneously built, and the predictive efficiency of DL methods and traditional models was compared. For model performance and internal validation, the Harrell’s concordance index (C-index) was used to calculate the predictive accuracy based on the bootstrap technique. To compare the different models, patients with HF were stratified into low-risk and high-risk groups according to the median risk predicted with each method, and survival prediction was assessed using Kaplan–Meier curves. A log-rank test was performed to discern whether these subgroups exhibited significantly different survival outcomes. Procedures of model construction are shown in Figure 1.

Results

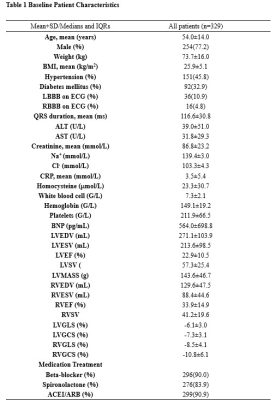

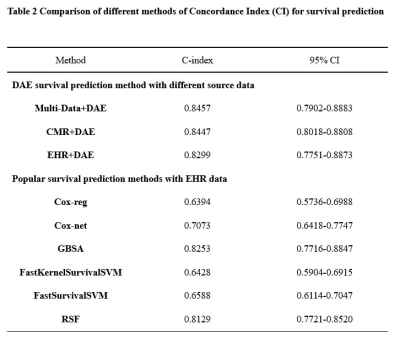

A total of 329 patients were finally evaluated (age 54 ± 14 years; men, 254) in this study in Table 1. During a median follow-up period of 1041 days, 62 patients experienced MACEs and their median survival time was 495 days. Among these patients, 51 died because of cardiovascular diseases, 8 were re-hospitalized because of the aggravation of the HF symptoms and 3 underwent cardiac transplantation.Bootstrap-based internal validation was used to verify the accuracy and consistency of the prediction model according to the guidelines recommended for TRIPOD8.When compared with conventional Cox hazard prediction models, deep learning models showed better survival prediction performance. Multi-data denoising autoencoder (DAE) model reached the the best optimism-corrected concordance index of 0.8546 (95% CI: 0.7902–0.8883).

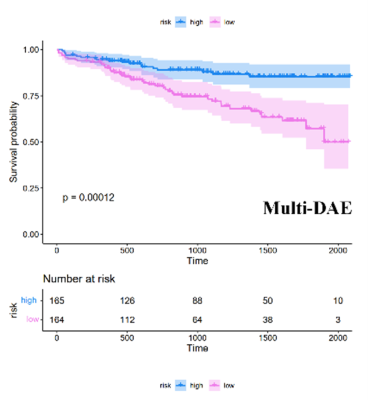

Furthermore, when divided into phenogroups, the multi-data DAE model could significantly discriminate between the survival outcomes of the high-risk and low-risk groups (P < 0.001) in Figure 2.

Discussion

In this study, a DL survival model based on cardiac non-contrast cine images was developed and validated. The major finding of the study was that the DL-based multi-DAE model exhibited better prognostic value when compared with conventional prediction models, which could be helpful in the risk stratification of patients with HF.Given its noninvasive characteristics and high accuracy, CMR has become the modality of choice for the assessment of in-vivo cardiac status. For patients with HF, CMR can provide function and volume indices and have been conventionally used to reflect motion conditions for risk stratification9. However, during advanced-phase study, we found that most patients were in stage C or D with severely impaired function in the study cohort, which may limit the prediction value of CMR.

AI is the current trend in analysis of cardiovascular imaging modalities in evaluating certain cardiovascular disease against the general background of the popularity of big data7,10. The use of AI has a far-reaching impact on all aspects of CMR. Our DL model proposed a new algorithm creatively combined the motion and clinical feature together to make assessment of prognosis in patients with HF. The application of the model can provide a more convenient and accurate prognostic prediction method for patients with HFrEF and expand the territory of AI in the field of HF prognosis.

Conclusion

The proposed deep learning model based on non-contrast cardiac cine magnetic resonance imaging could independently predict the outcome of patients with HFrEF and showed better prediction efficiency than conventional methods.Acknowledgements

No acknowledgement found.References

1. Savarese G, Becher PM, Lund LH, Seferovic P, Rosano GMC, Coats A. Global burden of heart failure: A comprehensive and updated review of epidemiology [published online ahead of print, 2022 Feb 12]. Cardiovasc Res. 2022;cvac013.

2. McDonagh TA, Metra M, Adamo M, Gardner RS, Baumbach A, Böhm M, Burri H, Butler J, Čelutkienė J, Chioncel O, Cleland JGF, Coats AJS, Crespo-Leiro MG, Farmakis D, Gilard M, Heymans S, Hoes AW, Jaarsma T, Jankowska EA, Lainscak M, Lam CSP, Lyon AR, McMurray JJV, Mebazaa A, Mindham R, Muneretto C, Francesco Piepoli M, Price S, Rosano GMC, Ruschitzka F, Kathrine Skibelund A; ESC Scientific Document Group. 2021 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Eur Heart J. 2021 Sep 21;42(36):3599-3726.

3. Ambrosy AP, Fonarow GC, Butler J, et al. The global health and economic burden of hospitalizations for heart failure: lessons learned from hospitalized heart failure registries. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63(12):1123-1133.

4. Heidenreich PA, Bozkurt B, Aguilar D, Allen LA, Byun JJ, Colvin MM, Deswal A, Drazner MH, Dunlay SM, Evers LR, Fang JC, Fedson SE, Fonarow GC, Hayek SS, Hernandez AF, Khazanie P, Kittleson MM, Lee CS, Link MS, Milano CA, Nnacheta LC, Sandhu AT, Stevenson LW, Vardeny O, Vest AR, Yancy CW. 2022 AHA/ACC/HFSA Guideline for the Management of Heart Failure: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2022 May 3;145(18):e895-e1032.

5. Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/HFSA Focused Update of the 2013 ACCF/AHA Guideline for the Management of Heart Failure: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Failure Society of America. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70(6):776-803.

6. Ponikowski P, Voors AA, Anker SD, et al. 2016 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: The Task Force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Developed with the special contribution of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur J Heart Fail. 2016;18(8):891-975.

7. Haq IU, Haq I, Xu B. Artificial intelligence in personalized cardiovascular medicine and cardiovascular imaging. Cardiovasc Diagn Ther. 2021 Jun;11(3):911-923.

8. Moons K, et al. Transparent reporting of a multivariable prediction model for Individual Prognosis Or Diagnosis (TRIPOD): Explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med. 2015; 162:W1–W73.

9. Rao RA, Jawaid O, Janish C, Raman SV. When to Use Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance in Patients with Heart Failure. Heart Fail Clin. 2021;17(1):1-8.

10. Litjens G, Ciompi F, Wolterink JM, et al. State-of-the-Art Deep Learning in Cardiovascular Image Analysis. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2019;12(8 Pt 1):1549-1565.

Figures