1879

Age and gender prediction from minimally processed 3D structural brain MRI through multi-task contrastive learning1Laboratory of Biomedical Imaging and Signal Processing, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China, 2Department of Electrical and Electronic Engineering, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

Synopsis

Keywords: Machine Learning/Artificial Intelligence, Machine Learning/Artificial Intelligence

Predicting brain age from structural MRI (sMRI) is potentially valuable as the deviation of predicted age from chronological age can be a biomarker for characterising brain health conditions. Currently, extensive pre-processing of sMRI data is required for most deep learning methods. This study presents a multi-task contrastive learning framework for simultaneous brain age prediction and gender classification from minimally processed, noisy 3D T1-weighted images. By including gender classification task and supervised contrastive learning, we demonstrate that leveraging gender information in training and better representation learning can boost age prediction accuracy for both in-domain and out-of-domain datasets.Introduction

Predicting brain age from structural MRI (sMRI) is potentially valuable because the deviation of predicted age from chronological age (i.e., predicted age difference/PAD) can be a biomarker for characterising brain health conditions including neurodegenerative diseases and mental illnesses.1-6 As brain morphology changes with ageing, unlike hand-engineering, deep learning (DL) method can learn to extract specialised features from sMRI, enabling reliable and accurate age prediction for acquiring PAD.Previous DL approaches3,7-11 rely on some if not extensive pre-processing of imaging data to homogenise brain volumes and extract structural features. Such time-consuming pre-processing might fail for rapidly-acquired images with low SNR. Meanwhile, most studies do not utilise gender label to support learning of age prediction. Models solely based on sMRI may misinterpret gender differences as ageing because there are small gender-related morphological differences.12,13

Recently, supervised contrastive learning (SupCon)14 has been proposed for improving downstream image classification task by learning to better cluster samples with the same label in the feature space. The extension of SupCon to regression problem by AdaCon15 shines a possibility of allowing better representation learning of sMRI for brain age prediction, potentially reducing the requirement of pre-processing to achieve better performance.

This study explores the feasibility of performing age and gender prediction utilising minimally processed, noisy images. We also investigate the effectiveness of representation learning and leveraging gender labels on improving brain age prediction via a multi-task framework which incorporates SupCon and gender classification.

Methods

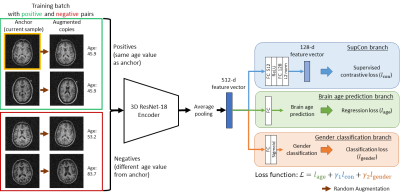

The proposed framework is illustrated in Figure 1. 3D ResNet-18 was adopted as the encoder. We followed the AdaCon15 implementation for contrastive learning with adaptive-margin supervised contrastive loss ($$$l_{con}$$$). The age prediction and gender classification branch were supervised by L1 loss ($$$l_{age}$$$) and binary cross-entropy loss ($$$l_{gender}$$$) respectively. The multi-task loss function $$$\mathcal{L}$$$: $$\mathcal{L} = l_{age} + \gamma_1l_{con} + \gamma_2l_{gender}$$Where $$${\gamma_1=0.1, \gamma_2=1}$$$

Data and Pre-processing

Raw structural T1-weighted data were obtained from cognitively unimpaired subjects from OASIS16,17 and IXI18 datasets. The combined dataset was randomly partitioned into training/validation/testing sets (n=2255/486/483). An additional ADNI1/GO dataset19 consisting of 1145 unprocessed T1-weighted scans was acquired for assessing generalisation performance. The dataset statistics are listed in Table 1. Data were resampled to 2x2x2mm3 resolution with dimensions 128x128x128 and zero-mean normalised. We added 40% Rician noise to simulate low SNR scenarios.

Training and Testing

Three networks were considered:

- Baseline (only brain age prediction)

- Brain age prediction with SupCon (Age+SupCon)

- Proposed network with SupCon and gender classification (Age+SupCon+Gender)

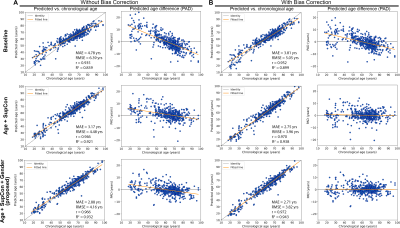

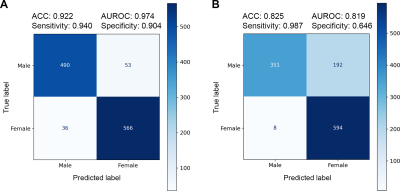

The age prediction accuracy was evaluated on both hold-out and out-of-domain ADNI testing sets by metrics: mean absolute error (MAE), root-mean-squared error (RMSE), Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r) and R2 score. Bias of predicted brain age was statistically corrected via linear modelling of PAD using the validation data20-22. The gender classification performance was also tested on both testing sets.

Results

Figure 2 presents plots of predicted brain age and PAD vs. chronological age for the hold-out testing set. The proposed Age+SupCon+Gender network clearly outperformed both baseline and Age+SupCon network in all quantitative metrics. The baseline network was overfitted to older brains, hence producing significantly higher MAE for younger brains. Bias correction helped to reduce dependence of PAD on chronological age, except for baseline. Figure 3 shows the age prediction performance of networks on external ADNI dataset. The performance improvement due to SupCon and auxiliary gender classification task of proposed network was not limited to in-domain testing set, but also applicable to external dataset. Figure 4A shows that the proposed network was capable to achieved high gender classification accuracy in the hold-out testing set. For out-of-domain ADNI testing set (Fig.4B), however, the classifier did suffer from some accuracy degradation (92% to 83%) due to domain shift. It tended to misclassify males as females (low specificity). This may be related to gender class imbalance issue (Table 1).Discussion and Conclusions

Using minimally processed and noisy sMRI data, the baseline (typical brain age prediction network) gave sub-optimal age prediction performance. However, by including SupCon under the multi-task learning framework, the prediction accuracy was significantly improved. This indicates that supervised learning with only regression loss may not guide the network to extract effective features. Furthermore, the boost in prediction accuracy via addition of gender classification branch on top of SupCon signifies the efficacy of introducing gender information with multi-task learning. Although the proposed framework achieved better testing performance on external dataset than baseline, high MAE and low R2 score suggest the need of transfer learning. Further investigation into advancing feature representation learning is important for enhancing performance and robustness of sMRI-based brain age prediction network without excessive pre-processing.More robust validation of age prediction performance is warranted such as performing reproducibility test to quantify network’s prediction variability on augmented samples of the same age. Since brain age (and therefore PAD) varies among subjects of the same chronological age due to other confounding factors like different lifestyles, genetics, pure use of MAE as metric might be misleading.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by Hong Kong Research Grant Council (R7003-19F, HKU17112120, HKU17127121 and HKU17127022 to E.X.W., and HKU17103819, HKU17104020 and HKU17127021 to A.T.L.L.), Lam Woo Foundation, and Guangdong Key Technologies for AD Diagnostic and Treatment of Brain (2018B030336001) to E.X.W.References

1. Cole JH. Multimodality neuroimaging brain-age in UK biobank: relationship to biomedical, lifestyle, and cognitive factors. Neurobiol Aging 2020;92:34-42.

2. Cole JH, Franke K. Predicting Age Using Neuroimaging: Innovative Brain Ageing Biomarkers. Trends Neurosci 2017;40(12):681-690.

3. Cole JH, Poudel RPK, Tsagkrasoulis D, Caan MWA, Steves C, Spector TD et al. Predicting brain age with deep learning from raw imaging data results in a reliable and heritable biomarker. Neuroimage 2017;163:115-124.

4. Franke K, Gaser C. Longitudinal changes in individual BrainAGE in healthy aging, mild cognitive impairment, and Alzheimer’s disease. GeroPsych: The Journal of Gerontopsychology and Geriatric Psychiatry 2012;25:235-245.

5. Koutsouleris N, Davatzikos C, Borgwardt S, Gaser C, Bottlender R, Frodl T et al. Accelerated brain aging in schizophrenia and beyond: a neuroanatomical marker of psychiatric disorders. Schizophr Bull 2014;40(5):1140-1153.

6. Schnack HG, Van Haren NE, Nieuwenhuis M, Hulshoff Pol HE, Cahn W, Kahn RS. Accelerated brain aging in schizophrenia: a longitudinal pattern recognition study. American Journal of Psychiatry 2016;173(6):607-616.

7. Bellantuono L, Marzano L, La Rocca M, Duncan D, Lombardi A, Maggipinto T et al. Predicting brain age with complex networks: From adolescence to adulthood. NeuroImage 2021;225:117458.

8. Jiang H, Lu N, Chen K, Yao L, Li K, Zhang J et al. Predicting Brain Age of Healthy Adults Based on Structural MRI Parcellation Using Convolutional Neural Networks. Front Neurol 2019;10:1346.

9. Peng H, Gong W, Beckmann CF, Vedaldi A, Smith SM. Accurate brain age prediction with lightweight deep neural networks. Medical Image Analysis 2021;68:101871.

10. Cheng J, Liu Z, Guan H, Wu Z, Zhu H, Jiang J et al. Brain age estimation from MRI using cascade networks with ranking loss. IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging 2021;40(12):3400-3412.

11. Jonsson BA, Bjornsdottir G, Thorgeirsson TE, Ellingsen LM, Walters GB, Gudbjartsson DF et al. Brain age prediction using deep learning uncovers associated sequence variants. Nature Communications 2019;10(1):5409.

12. Lotze M, Domin M, Gerlach FH, Gaser C, Lueders E, Schmidt CO et al. Novel findings from 2,838 Adult Brains on Sex Differences in Gray Matter Brain Volume. Scientific Reports 2019;9(1):1671.

13. Ritchie SJ, Cox SR, Shen X, Lombardo MV, Reus LM, Alloza C et al. Sex Differences in the Adult Human Brain: Evidence from 5216 UK Biobank Participants. Cerebral Cortex 2018;28(8):2959-2975.

14. Khosla P, Teterwak P, Wang C, Sarna A, Tian Y, Isola P et al. Supervised contrastive learning. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2020;33:18661-18673.

15. Dai W, Li X, Chiu WHK, Kuo MD, Cheng K-T. Adaptive Contrast for Image Regression in Computer-Aided Disease Assessment. IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging 2021;41(5):1255-1268.

16. Marcus DS, Wang TH, Parker J, Csernansky JG, Morris JC, Buckner RL. Open Access Series of Imaging Studies (OASIS): Cross-sectional MRI Data in Young, Middle Aged, Nondemented, and Demented Older Adults. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience 2007;19(9):1498-1507.

17. LaMontagne PJ, Benzinger TL, Morris JC, Keefe S, Hornbeck R, Xiong C et al. OASIS-3: Longitudinal Neuroimaging, Clinical, and Cognitive Dataset for Normal Aging and Alzheimer Disease. medRxiv 2019:2019.2012.2013.19014902.

18. Information eXtraction from Images (IXI) Dataset. brain-development.org.

19. Petersen RC, Aisen PS, Beckett LA, Donohue MC, Gamst AC, Harvey DJ et al. Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI): clinical characterization. Neurology 2010;74(3):201-209.

20. Beheshti I, Nugent S, Potvin O, Duchesne S. Bias-adjustment in neuroimaging-based brain age frameworks: A robust scheme. NeuroImage: Clinical 2019;24:102063.

21. de Lange A-MG, Kaufmann T, van der Meer D, Maglanoc LA, Alnæs D, Moberget T et al. Population-based neuroimaging reveals traces of childbirth in the maternal brain. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2019;116(44):22341-22346.

22. Liang H, Zhang F, Niu X. Investigating systematic bias in brain age estimation with application to post-traumatic stress disorders. Hum Brain Mapp 2019;40(11):3143-3152.

Figures

Fig. 1. Illustration of the proposed multi-task contrastive learning framework. During training, random augmentations are applied to samples in the batch to generate additional views of samples. This increases number of possible positive and negative pairs for supervised contrastive learning (SupCon). Hence, for batch size=N, there are 2N sample/age label pairs. During testing, no augmentation of samples is needed, and the SupCon branch can be discarded so the network only produces brain age prediction and gender classification as outputs.