1865

Positive Predictive Value of Multiparametric MRI in Detection of Prostate cancer: A Tertiary Center Retrospective Study

Zachary Franks1, Jarrett Rosenberg1, Richard E. Fan1, Geoffrey Sonn1, and Pejman Ghanouni1

1Stanford Health Care, Stanford, CA, United States

1Stanford Health Care, Stanford, CA, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Prostate, Cancer

Prostate Imaging Reporting and Data System (PIRADS) guidelines are used as a standard to help radiologists diminish variation in the acquisition, interpretation, and reporting of multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging (mpMRI) for prostate cancer diagnosis. However, the performance of mpMRI has been shown to vary across radiologists. A retrospective study was performed at a tertiary care center to assess the range of positive predictive values (PPV) across individual radiologists interpreting mpMRI in detecting any prostate cancer compared to targeted MR-US guided fusion biopsy pathology results.Introduction

Multi-parametric magnetic resonance imaging (mpMRI) of the prostate in addition to MRI-targeted biopsy aid in detection of more clinically significant prostate cancers and fewer clinically insignificant prostate cancers compared with standard systematic biopsy alone.1 High variability of positive predictive value (PPV) on detection of clinically significant prostate cancer has been shown across multiple centers utilizing the Prostate Imaging and Reporting Data System (PIRADS) version 2 and mpMRI; PPV has been shown to range from 35% for PIRADS scores of 3-5 and 49% for PIRADS 4-5.2,5 While some studies have shown that experience and number of prostate MR exams interpreted by the individual radiologist contributes to improving PPV, others have shown no improvement in performance with increasing case number.3,4Our objective was to evaluate our individual radiologists PPV for detection of prostate cancer, in addition to exploring factors that may contribute to variability of prostate MR interpretation such as PSA density, prostate zonal location and prostate volume.

Methods

A cohort of 1544 prostate lesions described on mpMRI based on PIRADS score ≥ 3 from 1,028 patients who underwent MRI ultrasound fusion targeted biopsy from 2017 to 2022 were retrospectively analyzed. Consent was obtained for the retrospective data collection under a protocol approved by the institutional review board. We included subjects undergoing either initial or repeat biopsy with MRI interpretation performed by our institutional attending radiologists.Multi-parametric MRI was performed utilizing a GE 3 Tesla scanner and an external 32-channel body array coil in prostate mode (peripheral channels not used). The imaging protocol was within the ACR PIRADS guidelines. MRI scans were interpreted using PIRADS version 2 by a Body fellowship-trained attending radiologist as part of routine clinical care and were not re-read prior to analysis. Clinical information was made available to radiologists at the time of interpretation. A total of 14 radiologists varied in years of prostate MRI experience.

Two urologists performed MRI-US fusion targeted and systematic prostate biopsies according to standard protocol. Tissue cores were sent for histopathologic evaluation defining prostate cancer as at least Gleason 3+3 (Gleason Grade Group 1).

The goal was to determine the positive predictive value (PPV) of the individual radiologist comparing the PIRADS 2 lesion score and the histopathologic results of MRI-US fusion biopsy. Individual effect of prostate volume, PSA, PSA density, transitional vs peripheral zone lesion location, base vs mid-gland vs apical lesion location, and PIRADS score on PPV were assessed by univariable logistic regression adjusted for clustering within patients. A multivariable logistic regression using just the significant

univariable factors as well as radiologist was also fitted. The omnibus test of radiologist effect was used to assess heterogeneity among radiologists. Heterogeneity among radiologists in PPV was also assessed by a meta-analysis type random-effects model using a logit transformation and inverse-variance weighting. A model stratified on prostate volume was also fitted to adjust for the latter's influence. The I^2 measure (percentage of total variability due to heterogeneity) was used to assess heterogeneity. All statistical analyses were done use Stata 16.1 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX) and R version 4.1.3 (r-project.org) and version 4.11-0 of package "meta".

Results

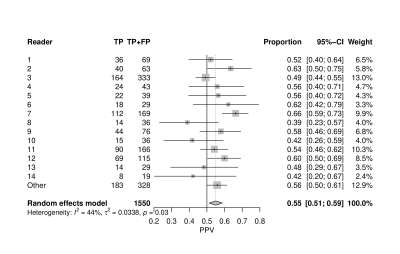

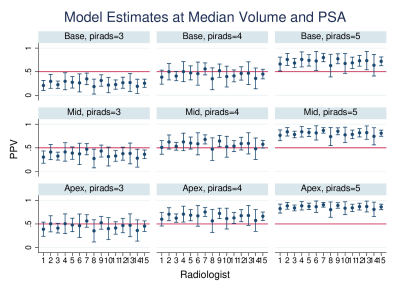

There were up to 6 lesions per patient, although 67% of patients only had 1. Factors that varied among radiologists included PSA density, zonal location and prostate volume (Table 1). PPV among radiologists for prostate lesion detection ranged from 39% to 66% with an average of 55% (Fig. 1). Multivariable analysis revealed prostate gland volume, PSA, PIRADS category and apex location were all significant predictors of PPV (p < 0.005), with volume negatively associated with PPV.Table 2 highlights the individual PIRADS categories PPV (P<0.001). When adjusting for gland volume (median 46 cc), the variability of PPV decreased (Fig. 2) and PPV overall increased (PPV 70% versus 41%). There was variability of PPV based on lesion location within the prostate gland and PIRADS category with the median prostate volume and PSA values held constant (PSA median 7.1) (Fig. 3). The omnibus test of radiologist was not significant (p=0.497), suggesting relative homogeneity among them in PPV once other factors were accounted for.

Discussion

Although a wide range of variability exists among our radiologists PPV in detection of prostate cancer (Gleason 3+3 or higher), the average of 55% is higher than prior multi-institutional averages of 35% for all PIRADS 3-5 lesions.5 PPV improved and heterogeneity in PPV was reduced with a smaller gland volume, likely due to the increased number of transitional zone lesions called in larger glands. Improvement in PPV with lesions described in the apex of the gland may be secondary to increased rectal gas artifact at the base of the gland on DWI sequences.Conclusion

While the positive predictive value of radiologists for detection of prostate cancer is higher than outside reports, this analysis suggests caution when reviewing mpMRI of larger prostates, especially in assessing the transition zone.Acknowledgements

Stanford Medicine - Department of Radiology, Body MRIReferences

- Kasivisvanathan V, et al. MRI-Targeted or Standard Biopsy for Prostate-Cancer Diagnosis. N Engl J Med. 2018 May 10;378(19):1767-1777. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1801993. Epub 2018 Mar 18. PMID: 29552975; PMCID: PMC9084630.

- Purysko AS, et al. PI-RADS Version 2.1: A Critical Review, From the AJR Special Series on Radiology Reporting and Data Systems. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2021 Jan;216(1):20-32. doi: 10.2214/AJR.20.24495. Epub 2020 Nov 19. PMID: 32997518.

- Salka BR, et al. Effect of Prostate MRI Interpretation Experience on PPV Using PI-RADS Version 2: A 6-Year Assessment Among Eight Fellowship-Trained Radiologists. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2022 Sep;219(3):453-460. doi: 10.2214/AJR.22.27421. Epub 2022 Mar 23. PMID: 35319914.

- Sonn GA, Fan RE, Ghanouni P, Wang NN, Brooks JD, Loening AM, Daniel BL, To'o KJ, Thong AE, Leppert JT. Prostate Magnetic Resonance Imaging Interpretation Varies Substantially Across Radiologists. Eur Urol Focus. 2019 Jul;5(4):592-599. doi: 10.1016/j.euf.2017.11.010. Epub 2017 Dec 7. PMID: 29226826.

- Westphalen AC, et al. Variability of the Positive Predictive Value of PI-RADS for Prostate MRI across 26 Centers: Experience of the Society of Abdominal Radiology Prostate Cancer Disease-focused Panel. Radiology. 2020 Jul;296(1):76-84. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020190646. Epub 2020 Apr 21. PMID: 32315265; PMCID: PMC7373346.

Figures

Table 1: Variation factors among radiologists.

Table 2: Overall Positive Predictive Value of radiologist MR interpretation based on PIRADS category.

Figure 1: Positive Predictive Value of MR in detection of clinically significant prostate cancer.

Figure 2: Positive Predictive Value in Reference to Gland Volume for detection of clinically significant prostate cancer.

Figure 3: Positive predictive value based on location and PIRADS score in the prostate gland in detection of clinically significant prostate cancer at Median volume of 46 cc and Median PSA.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.58530/2023/1865