1838

HP 13C pyruvate MRS reveals that ATP Citrate Lyase regulates alanine aminotransferase activity in the db/db liver.1Department of Radiology and Research Institute of Radiological Science, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea, Republic of, 2Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea, Republic of

Synopsis

Keywords: Liver, Hyperpolarized MR (Non-Gas)

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and diabetes are known to be closely related, but the mechanism has not been defined yet. The metabolic feature of the diabetic liver is that gluconeogenesis and fatty acid synthesis increase simultaneously. In this study, we hypothesized that ATP citrate lyase (ACLY) would play an essential role in inducing metabolic contradiction in the diabetic liver and investigate ACLY’s role on carbohydrate metabolism using hyperpolarized (HP) 13C pyruvate magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) and primary mouse hepatocytes.Introduction

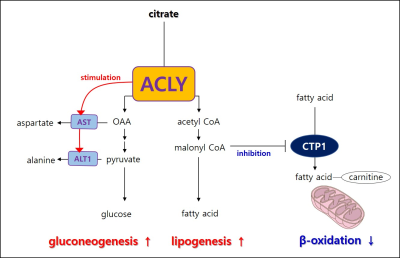

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) ranges from simple steatosis to nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) and is an emerging global health problem with nearly 25% of the world's population. In that 37% of type 2 diabetes mellitus patients developed NASH, it is essential to understand the relationship between diabetes and NAFLD1, 2. A characteristic of hepatic metabolism in diabetes is that both endogenous glucose production and fatty accumulation increase. However, metabolically these two features contradict each other. Gluconeogenesis is the metabolic process that supports glucose when energy is insufficient, whereas fatty acid synthesis stores excess energy. Citrate is involved in glucose and fatty acid metabolism, and ATP citrate lyase (ACLY) cleaves citrate to oxaloacetate (OAA) and acetyl CoA in the cytoplasm. In that OAA takes part in gluconeogenesis and acetyl CoA in fatty acid synthesis, we hypothesize that ACLY activation leads to hyperglycemia and fatty liver in diabetes. Since ACLY role in fatty acid synthesis is being primarily studied, we investigate ACLY's role in carbohydrate metabolism. In this study, we performed HP[1-13C]pyruvate MRS in the diabetic liver using db/db mouse and investigated the ACLY role of glucose production in primary hepatocytes.Methods.

All animal procedures were approved by the International Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of the Yonsei University Animal Research Center (YLARC; permission no. 2019-0219) following the National Institutes of Health guidelines. Diabetic mice C57BLKS/J-db/db were used, and C57BLKS/J-m/m mice were used as control mice. The first HP[1-13C]pyruvate MRS was performed in the liver after fasting for 20 hours at 14 -16weeks. The second was performed 2-4hours after oral administration of 2.5mg/kg of BMS 303141 at 20-22weeks. All MRI experiments were performed on a 9.4T animal MRI scanner using a 1H-13C dual-tuned mouse body transmit/receive coil (Bruker BioSpin MRI, Ettlingen, Germany). Effects on serum glucose level of BMS-303141, ACLY inhibitor, was measured for 200~300min after in db/db mice or 60% high fat diet fed for 6 months mice. Primary hepatocyte was isolated in the ICR mice. After harvesting the primary hepatocyte, the empty or ACLY expression plasmid was transfected using NEPA 21 Eletroporator. After overnight adherence, a glucose production assay was performed in the media when cells were exposed 3 hours to glucose-free DMEM with 20mM sodium lactate, 2mM sodium pyruvate, 2mM L-glutamine, 2mM alanine, and 15mM HEPES with 100ng/ml of glucagon.Results and discussion.

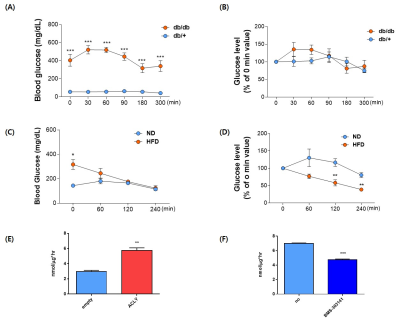

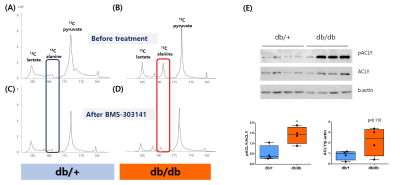

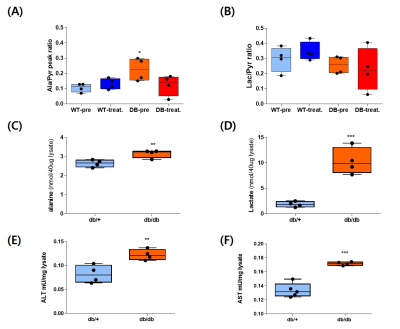

A single administration of BMS-303141 did not change blood glucose levels in control mice. On the other hand, the blood glucose level slightly increased within 60min and slightly decreased at 180min in db/db mice (Fig. 1A-B). The glucose-lowering effect was seen in mice fed a 60% high-fat diet, not in a standard diet (Fig. 1C-D). Endogenous glucose production increased in the ACLY over-expression cells (Fig 1E) and decreased by ACLY inhibitors (Fig. 1F) in the primary hepatocyte. These suggest ACLY regulates gluconeogenesis. When we performed HP[1-13C]pyruvate MRS, a prominent [1-13C]alanine peak was detected in the liver of db/db mice (Fig.2B), and it was decreased by the BMS-303141 administration (Fig.2D), but there was no difference in the control mice (Fig. 2A, C). HP[1-13C]alanie/pyruvate ratio was increased in db/db mice, and it was decreased after administration of ACLY inhibitor (Fig 3A). However HP [1-13C]lactate/pyruvate ratio was not different (Fig 2B). Since the signal intensity of HP MR reflects the amount of the pool size3, we measured the levels of alanine and lactate in the liver. Alanine level was increased in the db/db mice(Fig 3C). Interestingly lactate level was also increased in the db/db mice (Fig 3D). These results indicate that the pool size is not the only factor for the intensity of HP13C MRS. When we measured the ACLY protein levels in the liver, phosphorylated ACLY on Ser 455, the active form, increased (data not shown). These results indicate that ACLY is activated in db/db mice to increase HP[1-13C]alanine production, which may explain why the effect of BMS-303141 was only seen in db/db mice. With the consistency of HP alanine/pyruvate ratio, ALT activity increased (Fig 3.E) in db/db. Also, aspartate aminotransferase (AST) increased (Fig 3.F). From our results, we propose the ACLY is activated in the diabetic liver, which is a crucial player in increasing both glucose production and fatty acid synthesis in the diabetic liver. ACLY-mediated OAA activates ALT and AST activity and gluconeogenesis. At the same time, ACLY-mediated acetyl-CoA can provide a building block for fatty acid synthesis (Fig 4).Conclusion

This study suggests that activation of ACLY is a major cause of the simultaneous increase of gluconeogenesis and fatty acid synthesis in diabetic liver and that ACLY plays a vital role in regulating liver ALT activity. With the recent reports of the importance of ALT in gluconeogenesis from amino acid4, 5, our results support the clinical applicability of the ACLY target drugs and show the possibility of HP 13C pyruvate MRS in the early diagnosis of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis.Acknowledgements

This research was supported by Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea(NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education (2020R1I1A1A01065063)References

1. Vieira Barbosa, J. and M. Lai, Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease Screening in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Patients in the Primary Care Setting. Hepatol Commun, 2021. 5(2): p. 158-167.

2. Younossi, Z.M., et al., Global epidemiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease-Meta-analytic assessment of prevalence, incidence, and outcomes. Hepatology, 2016. 64(1): p. 73-84.

3. Day, S.E., et al., Detecting tumor response to treatment using hyperpolarized 13C magnetic resonance imaging and spectroscopy. Nat Med, 2007. 13(11): p. 1382-7.

4. Martino, M.R., et al., Silencing alanine transaminase 2 in diabetic liver attenuates hyperglycemia by reducing gluconeogenesis from amino acids. Cell Rep, 2022. 39(4): p. 110733.

5. Okun, J.G., et al., Liver alanine catabolism promotes skeletal muscle atrophy and hyperglycaemia in type 2 diabetes. Nat Metab, 2021. 3(3): p. 394-409.

Figures