1837

Evaluation of body motion at various patient position in a 0.5 T Upright scanner1SPMIC, University of Nottingham, Nottingham, United Kingdom

Synopsis

Keywords: Motion Correction, Motion Correction, Marker based tracking

Body motion at nine typical upright MRI poses (standing, seated, supine), have been characterised for several body positions (head, shoulder, sternum, hip) for 20 subjects over 30 s (free breathing); and 20 s (breath hold) and for 9 subjects over 10 minutes. Free-standing caused most motion; lying supine caused least. The use of a body support and breath-holding reduced motion. Net motion was similar over 50-1000 ms sampling periods. Respiratory-related motion could be removed from tracking data. The degree of motion identified in this work will inform future respiratory triggering and motion correction work.Introduction

Open MRI1 allows imaging of participants in various physiologically relevant positions, and with increased comfort particularly for scanning claustrophobic subjects and children. However, in the open configuration, the participant’s body motion2 is less constrained and cannot easily be limited by standard motion prevention approaches e.g. padding. In this study, the level of body motion (head, hips, torso) in different positions and over different time scales has been evaluated, to inform the development of motion correction methods for different sequences for whole body upright or open MRI.Methods

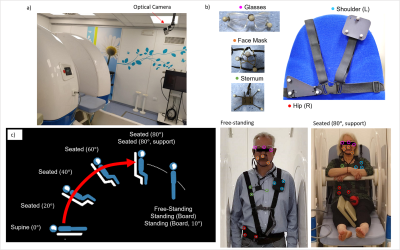

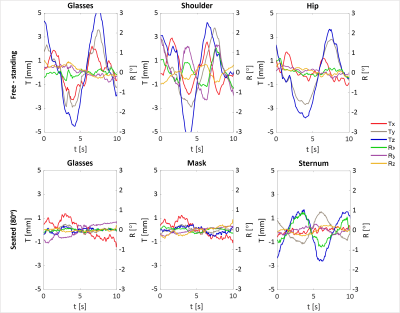

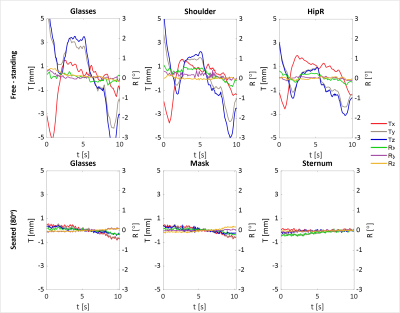

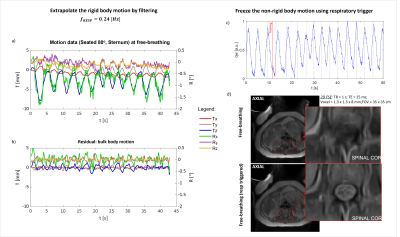

Fig.1 shows the experimental set-up. A dual optical camera for motion monitoring (https://optitrack.com/cameras/v120-duo/) was fixed 2m from (above and in front of) the magnet isocentre. Sets of three or more refractive markers were coupled together to form rigid bodies to be tracked by the camera. Marker supports (e.g. small board of ~8cm diameter, glasses or face mask) were then coupled to the body using belts or elastic bands. Head motion was tracked using two marker supports (face frame, glasses) and body motion using three (left shoulder, sternum, right hip) at a wide range of patient positions: seated at different bed angulations (80°,60°,40°,20°,0°), seated at 80° with arms supported in front of them, supine, free-standing, or standing leaning against supports (board) (Fig.1) to estimate the motion expected during an MRI scan. Measurements were conducted both during free-breathing (30 seconds, Fig.2) and breath-hold (20 seconds, Fig.3), with and without supports to limit movement. Measurements were performed on 20 healthy participants. Ten minutes of measurements in Free-standing and Seated 80° positions were also acquired for 9 volunteers. Data were used to evaluate changing in position over various intervals from 50ms to 1 minute, as relevant to motion in TE or TR MRI pulse sequences. Bulk body motion could be separated from respiration in free-breathing data using a band-stop filter. Marker-based respiratory triggering was implemented3, by detecting a respiration-like signal from the qw quaternion motion parameter of the rigid body coupled to the left shoulder. This was integrated in Matlab to trigger the MRI acquisition using a NI-DAQ card. Anatomical images were acquired using 2D FSE (TR=1s, TE=25ms, 1.3x1.3x8mm3 voxel size) at free-breathing without and with respiratory triggering for comparison.Results

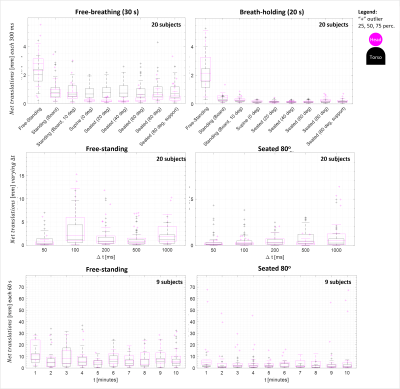

The rigid bodies were well detected by the camera, although small adjustments were required to guarantee their detection whilst maintaining the rigid coupling with the patient. The face-mask marker support was sensitive to jaw movements, producing similar results to the glasses support when instructing volunteers to tighten their jaw.Fig.2 shows an example of data acquired for all rigid bodies at 2 poses for one volunteer during free-breathing. The range of motion was reduced for the seated position and a respiration-like signal (~0.3Hz) and cardiac signals (~1.2Hz) were observed for some locations and conditions. Fig.4 shows the equivalent for the breath-hold condition. Fig.3a shows the box plots of the median of the net displacement in 300ms averaged over 20 subjects in different poses, for free-breathing and breath-hold conditions, (averaged over multiple 300ms blocks within the total acquisition time of 30s and 20s respectively). Net motion generally increased from supine to free-standing position. Fig.3b shows the net motion in different sampling intervals (measured within 1s). The data in Fig.3c, acquired after the experiment, shows how net motion across 1 minute remains fairly constant over 10 minutes (typical short scanning session). Fig.5a shows a body motion trace demonstrating considerable respiratory effects, Fig.5b shows the same trace with respiratory effects filtered out to reveal bulk motion. Fig.5c reports the respiratory component in qw used to trigger MRI acquisition to produce Fig.5d.Discussion

We have evaluated head and torso motion in various body poses over the duration of a typical MRI scan using optical markers in an MRI scanner. As expected, motion increases as the subject becomes more upright and less restricted in their freedom to move (e.g. by back board or arm rest). Head motion shows the random component observed in previous work3. Human movement approximately follows a random walk over the time period of an MRI scan and here we found that net movement did not depend particularly on sampling period (although 50ms was the minimum sampling time possible for this number of rigid bodies). This is significant, as the period over which net movement is relevant for motion correction will depend on the pulse sequence being used. In this work, we assessed the torso motion at three points (shoulder, sternum, hip) to enable evaluation of non-rigid body motion4,5,6. Almost all rigid bodies showed a respiration-like signal and sternum and shoulder markers produced signals usable for respiration triggering, although the strength of the respiratory signal varied with varying rigid body/camera relative orientation. In future work, motion of children and patient groups will be assessed, and data will be acquired over longer tracking sessions where people may get more uncomfortable. We will use the data from the different markers to identify the extent where the torso can be treated as a rigid body for motion correction in MRI.Conclusion

This characterization of motion represents an important step in controlling and correcting motion, including respiration in Open MRI geometry.Acknowledgements

I’d like to thank my research group for the amazing team working done to achieve these results.References

1. Marques J P, Simonis F F, Webb A G. Low-field MRI: An MR physics perspective. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2019;49:1528-1542. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmri.26637

2. Zaitsev M, Maclaren J, Herbst M. Motion artifacts in MRI: A complex problem with many partial solutions. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2015;42(4):887-901. (https://doi.org/10.1002/jmri.24850 )

3. Bortolotti L, Clennell I, Mougin O, Glower P, Bowtell R, Gowland P, “Using Body Motion Tracking Data at Various Patient Position to Implement Respiration Gating in a 0.5 T Paramed ASG Upright Scanner” MoCo workshop Proffered Papers - Poster 4 at "ISMRM Workshop on Motion Detection & Correction"

4. Hess A T, Alfaro-Almagro F, Andersson J L R, Smith S M. Head movement in UK Biobank, analysis of 42,874 fMRI motion logs. ISMRM Workshop on Motion Detection & Correction, Oxford 2022

5. Balakrishnan G, Durand F, Guttag J. Detecting Pulse from Head Motions in Video. Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR). 2013;3430-3437

6. Safavi S, Arthofer C, Cooper A, Harkin J, Prayle A, Sovani M, Bolton C, Gowland P, Hall I. Using an upright MRI system to assess the impact of posture on diaphragm morphology. European Respiratory Journal. 2019;54(63):PA3165, DOI: 10.1183/13993003.congress-2019.PA3165

7. Boulby P, Gowland P, Adams V, Spiller R C. Use of echo planar imaging to demonstrate the effect of posture on the intragastric distribution and emptying of an oil/water meal. Neurogastroenterology & Motility. 1997;9:41-47. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2982.1997.d01-6.x

8. Cao J J, Wang Y, Schapiro W, McLaughlin J, Cheng J, Passick M, Ngai N, Marcus P, Reichek N. Effects of respiratory cycle and body position on quantitative pulmonary perfusion by MRI. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2011;34:225-230. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmri.22527

Figures