1834

Combining FID navigators with field probe monitoring for improved head motion tracking and prospective correction at 7T1German Center for Neurodegenerative Diseases (DZNE), Bonn, Germany, 2Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of Bonn, Bonn, Germany

Synopsis

Keywords: Motion Correction, Motion Correction

FID navigators and field probes can measure local motion-induced magnetic field changes at different positions. Both methods are suited for marker-less prospective motion correction but with limited accuracy. A small 7T study with five subjects was performed to compare their performance for small involuntary and large voluntary motion. It is demonstrated that errors of regression models, calibrated between magnetic field measurements and motion parameters, are consistently reduced by combining both techniques. Furthermore, a proof-of-concept prospective motion correction experiment based on FID navigators is presented, which will be extended to include field probe measurements in the near future.Introduction

Prospective head motion correction (PMC) requires a tracking method which offers high accuracy and high temporal resolution. Free induction decay (FID) navigators (FIDnavs1) can be acquired rapidly and integration into an MR sequence is straight-forward. However, the intracranial FID signal is also modulated by other sources of B0 perturbations (e.g. gradient heating, chest motion), limiting its capability as a motion predictor. Magnetic field probes2 can be used to keep track of extracranial magnetic field changes, providing additional information about head motion. Until now, FIDnavs and field probes were only tested individually for motion tracking3,4. In this work, we demonstrate an improvement of FIDnav-based motion tracking at 7T by including external field measurements as additional predictors. In a first step, we implemented a FIDnav-based PMC workflow and demonstrated its potential in a proof-of-concept human MR experiment.Methods

Five healthy subjects were scanned at a MAGNETOM 7T Plus scanner (Siemens, Healthineers) equipped with a 32 channel Rx (1Tx) head coil. They were instructed to keep their head still for 3 minutes (involuntary motion), and then follow guided head motions for 3 minutes (shaking, nodding, horizontal and vertical figures of eight). A rapid 3D-EPI time series5 (TR = 290ms, whole-head, 3mm isotropic, 620 volumes) was acquired throughout each 3 minutes period to obtain "ground truth" motion parameters with MCFLIRT6. Before each 3D-EPI volume, a FID navigator (3° non-selective excitation, 2.5ms readout7) was acquired. Furthermore, 16 19F field probes were attached externally to the head coil8 in order to measure field probe signals simultaneously with the FIDnavs (2.5ms, "snapshot monitoring"). The 32 complex FIDnav signals and the 16 field measurements of the camera were tested separately and together as a predictor for motion using a simple linear regression model. The first half of each time series (1.5min) was used for subject-specific calibration and the second for testing. The analysis was repeated with switched calibration/test sets. For real-time PMC9, a single-subject scan (3D-EPI: TR=400ms, 310 volumes) with involuntary and voluntary motion was performed. For model calibration and PMC, the same motion paradigm (head shaking and nodding) was tested. During prospective correction, FIDnavs were received in real-time and corresponding field-of-view (FOV) updates were sent back to the scanner and applied during the next EPI volume acquisition. Residual motion is estimated with MCFLIRT. In order to evaluate the PMC performance, the actual ground truth motion is estimated from the difference between residual motion and applied FOV updates.Results

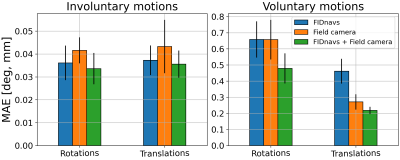

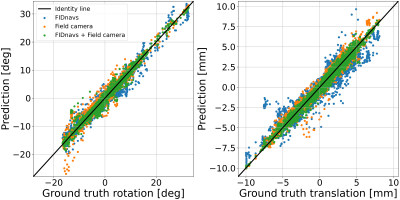

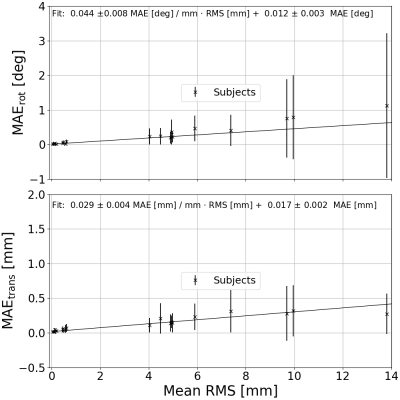

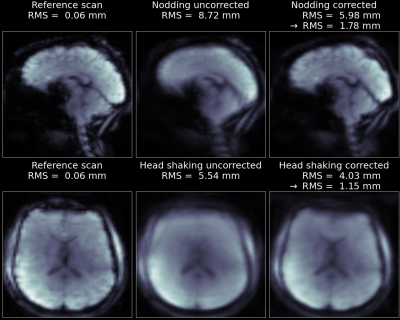

Fig. 1 shows the group mean absolute error (MAE) for different motion types and inputs. Field camera measurements yield smaller errors than FIDnavs for voluntary motion but show increased errors for involuntary motion. However, combining both signals as predictors leads to smallest overall error with a significant reduction of extreme outliers (visible for separate FIDnavs and field camera predictions in Fig. 2). Different scales of the MAEs as a function of the motion type (Fig. 1) indicate an amplitude-dependent error. This is also shown in Fig. 3, that puts the MAEs of the combined inputs in relation to the mean RMS deviation10 for each time series, revealing a proportionality. Averaged EPI images without and with PMC are shown in Fig. 4. Using the FIDnav-based prediction for PMC, less blurring and more visible structural details indicate a reduced amount of residual motion with PMC. A clear reduction of the mean RMS from the actual ground truth motion to residual motion is observed.Discussion

Minimized errors of the combined inputs compared to separate inputs indicate that both FIDnavs and externally mounted field probe measurements contain valuable, and potentially complementary information for predicting motion parameters. While FIDnavs demonstrate smaller errors in case of small motion, the field camera measurements offer higher accuracy for large motion. FIDnavs are more sensitive towards the intracranial field and could thus potentially measure small magnetic field changes by head motion more accurately. Although the field camera seems to be superior for large motion predictions, extreme outliers occur and can be reduced by combining both signals (Fig. 2). The proportionality between tracking errors and ground truth RMS is helpful to judge the average model performance for different motion amplitudes. Assuming that the mean RMS hardly exceeds 1.5mm (95 percentile of 1000 resting-state-fMRI scans (10min) from the Rhineland-Study11) in practice, MAEs of less than 0.08(1)° and 0.060(4)mm can be expected. The prospectively corrected images demonstrate a reduction in blurring artifacts which is also underlined by the reduced mean RMS compared to the ground truth mean RMS. However, the remaining motion is still visible and could be further reduced by a faster FOV update (and higher sampling rate of FIDnavs) and by improving the prediction accuracy (e.g. by including additional field camera measurements).Conclusion

FID-navigated motion tracking at 7T can be significantly improved by including field probe monitoring data. Even alone, statically mounted field probes are well-suited for simple regression-based motion tracking. The prospectively corrected images show a reduction in artifacts and future work will be focused on improving the PMC and including field probe measurements in the workflow. The initial results suggest that combined FIDnavs and field probe monitoring are promising for future reliable, highly accurate and marker-less head motion tracking and correction.Acknowledgements

This work received financial support from the European Union Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation program under grant agreement 885876 (AROMA).References

[1] Kober, T. et al. Head Motion Detection Using FID Navigators. MRM. 2011;66:135–143.

[2] Barmet, C. et al. Spatiotemporal magnetic field monitoring for MR. MRM. 2008;60(1):187-197.

[3] Babayeva, M. et al. Accuracy and Precision of Head Motion Information in Multi-Channel Free Induction Decay Navigators for Magnetic Resonance Imaging. IEEE. 2015;34(9):1879-1889.

[4] Bortolotti, L. et al. Measurement of head motion using a field camera in a 7T scanner. ISMRM 2020 abstract 0464

[5] Stirnberg, R. et al. Rapid whole-brain resting-state fMRI at 3T: Efficiency-optimized 3D-EPI vs. repetition time-matched simultaneous-multi-slice EPI. NeuroImage. 2017;163:81–92

[6] Jenkinson, M. et al.. Improved Optimisation for the Robust and Accurate Linear Registration and Motion Correction of Brain Images. NeuroImage. 2002;17(2):825-841.

[7] Stirnberg, R. et al. Rapid Fat Suppression for Three-Dimensional Echo Planar Imaging with Minimized Specific Absorption Rate. MRM. 2016;76(5):1517–23.

[8] Brunheim, S. et al. Replaceable field probe holder for the Nova coil on a 7 Tesla Siemens scanner. ISMRM 2020 abstract 3389

[9] Herbst, M. et al. Prospective motion correction with continuous gradient updates in diffusion weighted imaging. MRM. 2012;67(2):326-338.

[10] Jenkinson, M. Measuring Transformation Error by RMS Deviation. FMRIB Technical Report TR99MJ1

[11] Breteler, M. et al. Mri in the Rhineland Study: A Novel Protocol for Population Neuroimaging. Alzheimer’s & Dementia. 2014;10(4): P92–P92.

Figures