1833

Patient-specific respiratory liver motion analysis for individual motion-resolved reconstruction1Helmholtz Center Munich, Munich, Germany, 2School of Computation, Information and Technology, Technical University of Munich, Munich, Germany, 3Department of Diagnostic and Interventional Radiology, Technical University of Munich, Munich, Germany, 4Philips GmbH Market DACH, Hamburg, Germany, 5School of Biomedical Imaging and Imaging Sciences, King's College, London, United Kingdom

Synopsis

Keywords: Motion Correction, Liver

Respiratory motion is a major source of artefacts in abdominal MRI and varies considerably across subjects. Motion-resolved strategies utilize the periodic nature of respiratory motion, but do not always consider absolute patient-specific motion information. The purpose of the present work is to develop a framework incorporating the patient-specific absolute body motion into a motion-resolved reconstruction (XD-GRASP), while adapting different motion binning strategies. To explore the potential of respiratory motion knowledge for MR reconstruction, individual absolute body motion, i.e. of the liver, is identified.Introduction

Respiration causes local deformation of abdominal organs and induces motion artefacts in MR imaging. To utilize the periodic nature of respiratory motion, motion-resolved reconstruction methods such as eXtra-Dimensional Golden-angle RAdial Sparse Parallel eXtra-Dimensional (XD-GRASP) (1) have been proposed. XD-GRASP uses the radial stack-of-star self-navigation characteristic to retrospectively bin k-space data intomultiple motion states (MS), whereas the number of$$$\,$$$MS ($$$n_{MS}$$$) compromises between motion blurring (MS↓) and undersampling (MS↑). However, the extracted self-navigator only provides a relative motion curve and lacks absolute displacement values. The present work develops a framework to investigate individual organ motion and quantify subject-specific respiratory liver motion, and relates motion-resolved reconstructions to adapted binning strategies.Methods

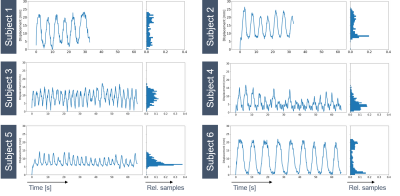

Motion EstimationPatient-specific liver motion was investigated on a free-breathing 2D real-time scan. Deformation vector fields $$$φ_t$$$ were derived by registering each image slice $$$\{m_{t}\}_{t=0}^{T-1}$$$ to one pre-selected end-exhale dynamic $$$f=m_T$$$ (Fig.1). Pairwise registration was performed with SimpleITK (2) using a three-layer multi-resolution strategy with dense deformation fields. Mean-squared-error was used as an image distance metric and iterative Gaussian smoothing enforced displacement regularity after each update step. Pre-processing included intensity clipping (0.5-99.5%) and rescaling (0-1) for the 2D+t volume. Motion field quality was evaluated by computing the Jacobian Determinant and normalized cross correlation (NCC) and structural similarity index (SSIM) between the target $$$f$$$ and warped source $$$m_t \circ \phi_t$$$. While the dense deformation fields provide information for the entire field of view, specific organ motion, i.e. the liver, is of interest. Therefore, a liver mask of$$$\,$$$the pre-selected end-exhale state is applied to each $$$\phi_{t}^{-1}$$$. 1D top liver displacement curves were generated by extracting and averaging the foot-head (FH) components of the upper 20%, assuming that the respiratory liver motion is dominated by motion in the FH direction.

Reconstruction

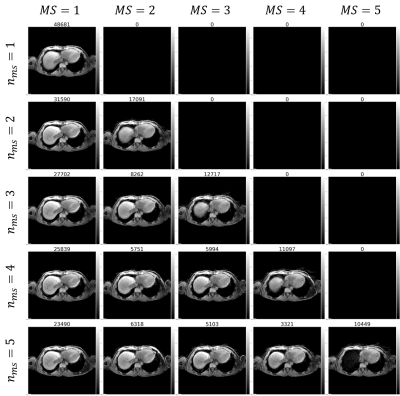

The$$$\,$$$motion-resolved reconstruction was evaluated on a free-breathing high-resolution 3D radial stack-of-stars (SoS) scan. The breathing curve was extracted from the IFFT of the k-space center along the partition direction using PCA (1). MS were extracted in two ways: (a) distributing the amount of spokes equally over all MS (1) and (b) sorting spokes into MS based on their relative displacement. Multiple $$$n_{MS}$$$ were defined for both cases. The motion-resolved reconstruction was performed in Julia (3), solving the inverse problem iteratively and slice-wise:

$$x = argmin_{x'} || FSx'-y|| + \alpha_1 ||D_t x'||_1 + \alpha_2 ||W_r x'||_1 $$

With x complex reconstructed images, y multi-coil k-space, F nonuniform fast Fourier transform, S the ESPIRiT coil sensitivity maps (4), $$$||D_t x'||_1$$$ a total variation regularization in the motion state dimension (1), $$$||W_r x'||_1$$$ a L1-Wavelet regularization in the spatial dimension (5), $$$\alpha1$$$=0.1 and $$$\alpha2$$$=0.005. To account for partial Fourier sampling in the partition encoding direction, first the image phase was reconstructed with low-resolution, followed by a full-resolution reconstruction of the magnitude images using a Homodyne-filtered k-space. The two echo images of each MS were further processed to decompose water and fat signals based on a dual echo adapted multi-resolution graph-cut algorithm (6, 7). Water images were used for qualitative evaluation of the reconstruction.

Data Acquisition

Measurements were performed at 3T (Ingenia Elition X, Philips Healthcare) on six volunteers with a 2D Gradient echo sequence (FOV=300x550mm2, TE/TR=2.1/0.95ms, spatial resolution=1.23x1.23mm2, dynamic scan time=110ms, 300/600 temporal slices, C-SENSE reduction=3.2) and a 3D scan (FOV=450x450x252mm³, voxelsize=1x1x1.5mm³, TR/TE1/TE2=4.9/1.4/2.7ms, 600 radial spokes per partition, flip angle=10°, partial Fourier factor in partition direction=3/4, $$$T_{shot}$$$=395ms).

Results

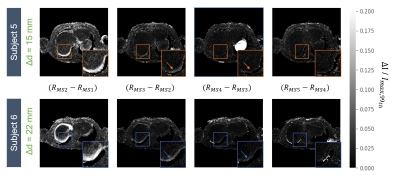

Motion field analysis revealed smooth deformation fields with %(detJφ< 0)<0.01%, NCC=0.71±0.03 and SSIM=0.82±0.03 over all subjects. 1D top liver displacement curves are seen in Fig.2, where inter-subject variability is observable regarding absolute displacement (14.3-26.4mm) and breathing frequency (0.12-0.38Hz). Motion-resolved reconstructions using the two binning methods are compared in Fig.3 for the recommended $$$n_{MS}$$$=4 (1). Although relative displacement motion binning (b) leads to varying amounts of sampling points per MS, no increase of undersampling artefacts is observable. However, for end-exhale less streaking is visible in (b). Fig.4 shows all dynamics for $$$n_{MS}$$$=1-5 for an exemplary subject using the proposed binning method. The subject-specific effect of increasing $$$n_{MS}$$$ is visible as difference between reconstructions ($$$Recon_{(n+1)MS} - Recon_{(n)MS}$$$) in Fig.5 for two subjects. While for subject 6 with larger liver displacement (∆d= 22mm), the recommended $$$n_{MS}$$$=4 shows improved motion deblurring compared to $$$n_{MS}$$$=3, it is less prominent for subject 5 with smaller liver displacement (∆d= 15mm).Discussion

Motion estimation results indicate strong inter-subject breathing pattern variability, which influences motion-resolved reconstructions, such as the effect of different $$$n_{MS}$$$. Motion binning based on relative displacement indicates the potential of increased sampling for the end-exhale MS (Fig.4). Still, the total variation constraint allows to benefit from the remaining MS, although they are less densely sampled. Patient-specific motion state adaptation may aid in reducing required data or correcting individual motion, but requires further investigation. Prior knowledge of the subjects motion pattern could be introduced into the reconstruction process, e.g. as quality metric (8), and aid in correction of typically discarded data.Conclusion

Extracting patient-specific absolute respiratory motion metrics can provide valuable information for motion-resolved reconstruction, especially in the case of periodic motion. The approach can easily be transferred to further organs. With analysis of an increased sample size, recommendations for defining SNR- and time-efficient patient-specific imaging protocols could be derived.Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge research support from Philips Healthcare. V.J.S. is supported by the Helmholtz Association under the joint research school "Munich School for Data Science - MUDS".

References

[1] Feng L, Axel L, Chandarana H, Block KT, Sodickson DK, Otazo R. XD-GRASP: Golden-angle radial MRI with reconstruction of extra motion-state dimensions using compressed sensing. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine 2016; 75:775–788. 10.1002/mrm.25665

[2] Yaniv Z, Lowekamp BC, Johnson HJ, Beare R. SimpleITK Image-Analysis Notebooks: a Collaborative Environment for Education and Reproducible Research. Journal of Digital Imaging 2018; 31:290–303.10.1007/s10278-017-0037-8

[3] Knopp T, Grosser M. MRIReco.jl: An MRI reconstruction framework written in Julia. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine 2021; 86:1633–1646. 10.1002/mrm.28792

[4] Uecker M, Lai P, Murphy MJ, Virtue P, Elad M, Pauly JM, Vasanawala SS, Lustig M. ESPIRiT-an eigenvalue approach to autocalibrating parallel MRI: Where SENSE meets GRAPPA. Magnetic Resonancein Medicine 2013; 71:990–1001. 10.1002/mrm.24751

[5] Lustig M, Donoho D, Pauly JM. Sparse MRI: The application of compressed sensing for rapid MR imaging. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine 2007; 58:1182–1195. 10.1002/mrm.21391

[6] Eggers H, Brendel B, Duijndam A, Herigault G. Dual-echo Dixon imaging with flexible choice of echo times. Magn Reson Med 2010; 65:96–107. 10.1002/mrm.22578

[7] Stelter JK, Boehm C, Ruschke S, Weiss K, Diefenbach MN, Wu M, Borde T, Schmidt GP, Makowski MR, Fallenberg EM, Karampinos DC. Hierarchical Multi-Resolution Graph-Cuts for Water-Fat-Silicone Separa-tion in Breast MRI. IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging 2022; 41:3253–3265. 10.1109/tmi.2022.3180302

[8] Machado IP, PuyolAntón E, Hammernik K, Cruz G, Ugurlu D, Olakorede I, Oksuz I, Ruijsink B, Castelo-Branco M, Young AA, Prieto C, Schnabel JA, King AP. A Deep Learning-based Integrated Framework for Quality-aware Undersampled Cine Cardiac MRI Reconstruction and Analysis.

Figures