1832

A Dynamic 2D TSE Acquisition Strategy for Robust SAMER Motion Mitigation1Siemens Healthcare GmbH, Erlangen, Germany, 2Siemens Medical Solutions, Boston, MA, United States, 3Shenzhen Magnetic Resonance, Shenzhen, China, 4Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, United States, 5A. A. Martinos Center for Biomedical Imaging, Charlestown, MA, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Motion Correction, Brain, Value, Clinical Application

Retrospective motion correction for 2D TSE/FSE is challenging due to interpolation through slices with gaps, interleaved slice orderings, and spin history effects. Optimized Cartesian sampling trajectories provide decreased motion sensitivity in specific situations but can also exacerbate motion sensitivity under typical patient motion. In this work, we introduce a dynamic acquisition strategy that determines the k-space lines acquired in the next shot based on the prior patient motion. Specifically, each TR dynamically encodes available lines which minimize motion variance. We show that this dynamic acquisition strategy results in improved reconstruction robustness under typical clinical motion scenarios.Background

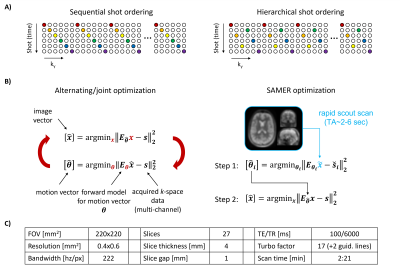

Although retrospective motion estimation in both 2D and 3D sequences has been demonstrated1-6, the correction of motion artifacts in 2D TSE/FSE is challenging due to gaps in k-space, thick slice interpolation, slice gaps, and spin history effects. A direct relationship between motion sensitivity, the robustness of retrospective correction, and the temporal acquisition of k-space has been established6. In 2D TSE sequences it is critical that the number and spacing of k-space lines in a shot remains fixed to preserve contrast, but there is temporal flexibility for the order in which k-space is filled (see the sequential or hierarchical orders shown in Fig. 1A). In specific situations, the hierarchical ordering provides decreased motion sensitivity compared to sequential, but a single fixed shot schedule has not been shown to generalize across all typical patient motions.Navigator-free retrospective motion correction1-4 often employs alternating/joint optimization, which is computationally demanding and can only be initiated upon completion of the acquisition (Fig. 1B). The recently proposed SAMER technique5,6 leverages an ultra-fast, low-resolution scout and repeated acquisition of a small number of motion guidance lines6 to decouple motion estimation from image reconstruction. This allows for very rapid and fully separable estimation of motion parameters shot-by-shot (TMotEst~1 sec / shot)6. We exploit this to allow for “on-the-fly” analysis of the image’s expected motion corruption and dynamically choose the next shot’s k-space lines to minimize motion sensitivity.

Methods

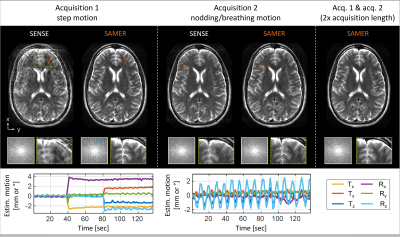

The SAMER framework with motion guidance lines was implemented into a 2D TSE sequence (Fig. 1C). On a healthy volunteer in vivo motion experiments were conducted at 3T (MAGNETOM Vida, Siemens Healthcare, Erlangen, Germany) with a 20-channel head coil.We first analyzed residual artifacts in 2D TSE SAMER reconstructions during instructed step and nodding/breathing motion experiments and show that the effects from k-space gaps and thick-slice interpolation can be largely overcome if the acquisition length is doubled4.

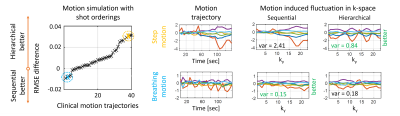

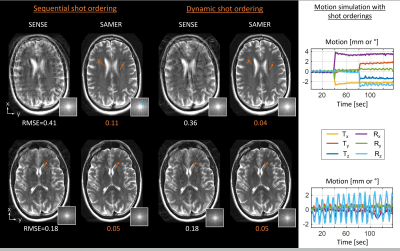

Next, we characterize the relationship between motion sensitivity, the robustness of retrospective correction, and the temporal acquisition of k-space. In simulation, 2D thick-slice TSE k-space data were produced utilizing 41 motion trajectories obtained from clinical scans7, and SAMER motion correction was performed using the ground truth motion parameters. The reconstruction performance using sequential and hierarchical orderings (Fig. 1A) was measured by RMSE with respect to the ground truth image.

Moreover, we propose an easy-to-compute motion variance metric that serves as a proxy for motion sensitivity and relies only on motion trajectory information. The motion variance metric is obtained by first low-pass filtering (LP) the motion curve $$$\theta$$$ as a function of the phase encoding direction $$$k_y$$$ and then computing the sum of variances.

$$MotionVariance=∑_{i=1}^6 Var(LP(\theta_i (k_y )))$$

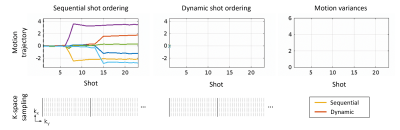

Using a running update of this metric from the SAMER on-the-fly motion estimates, we developed a dynamic algorithm for scheduling TSE shots. The most recent head-position estimate is used to determine which remaining shot position is most likely to reduce the temporal motion variance. We evaluated this dynamic acquisition strategy in motion simulation with step and nodding/breathing motion and compared the image quality and RMSE against standard sequential ordering. It is important to note that our dynamic strategy does not alter the number and spacing of k-space lines in a shot but creates a patient/exam specific permutation to the shot order that minimizes motion sensitivity.

Results

SAMER significantly reduced motion artifacts for in vivo acquisitions with instructed step and nodding/breathing motion (Fig. 2). However, some ringing/blurring artifacts are still visible due to gaps in k-space and thick-slice interpolation errors. These issues are resolved when data from two acquisitions (2× scan time) was used in the SAMER reconstruction.On average, the hierarchical ordering led to improved motion correction for many, but not all trajectories (Fig. 3). Also, Fig. 3 suggests that the hierarchical ordering is better for step motion (yellow), while the sequential ordering is superior for nodding/breathing motion (blue). This trend is also supported by the proposed motion variance metric which shows a ~3x reduction for hierarchical ordering in case of step motion.

Figure 4 shows the dynamic scheduling of TSE shots for a step motion experiment. As time progresses, the motion variance increases steeply for sequential ordering. Alternatively, the most recent SAMER motion estimate can be used to dynamically redistribute the shot order and maintain a low level of variation along the encoding direction.

In simulated motion data with sequential ordering, SAMER shows good reconstruction performance for breathing motion, but artifacts remain for step motion (Fig. 5). The proposed dynamic ordering adapts well to each motion scenario providing good image quality for both experiments and ~3x lower RMSE for the step motion case.

Conclusions

Optimized Cartesian sampling trajectories based on permutations of the TSE shot ordering can improve retrospective motion correction. However, a single shot schedule is unlikely to generalize across all typical patient motion. We introduced a dynamic acquisition strategy for 2D TSE which determines the next shot position based upon “on-the-fly” motion estimates provided by SAMER and a novel motion variance metric. The dynamic acquisition strategy was evaluated in simulation and resulted in improved reconstruction robustness. Future work is needed to confirm the performance of the dynamic algorithm in patients.Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by NIH research grants: 1P41EB030006-01, 5U01EB025121-03, and through research support provided by Siemens Medical Inc.References

[1] M. W. Haskell, S. F. Cauley, and L. L. Wald, “TArgeted Motion Estimation and Reduction (TAMER): Data consistency based motion mitigation for mri using a reduced model joint optimization,” IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging, vol. 37, no. 5, pp. 1253–1265, 2018.

[2] A. Loktyushin, H. Nickisch, R. Pohmann, and B. Schölkopf, “Blind multirigid retrospective motion correction of MR images,” Magn. Reson. Med., vol. 73, no. 4, pp. 1457–1468, 2015.

[3] J. Cordero-Grande, L., Teixeira, R., Hughes, E., Hutter, J., Price, A., & Hajnal, L. Cordero-Grande, R. P. A. G. Teixeira, E. J. Hughes, J. Hutter, A. N. Price, and J. V. Hajnal, “Sensitivity Encoding for Aligned Multishot Magnetic Resonance Reconstruction,” IEEE Trans. Comput. Imaging, vol. 2, no. 3, pp. 266–280, 2016.

[4] L. Cordero-Grande, E. J. Hughes, J. Hutter, A. N. Price, and J. V. Hajnal, “Three-dimensional motion corrected sensitivity encoding reconstruction for multi-shot multi-slice MRI: Application to neonatal brain imaging,” Magnetic Resonance in Medicine, vol. 79, no. 3, pp. 1365–1376, 2018.

[5] D. Polak, D. N. Splitthoff, B. Clifford, W. C. Lo, S. Y. Huang, J. Conklin, L. L. Wald, K. Setsompop, and S. Cauley, “Scout accelerated motion estimation and reduction (SAMER),” Magn. Reson. Med., vol. 87, no. 1, pp. 163–178, 2022.

[6] D. Polak, J. Hossbach, D. N. Splitthoff, B. Clifford, W.-C. Lo, A. Tabari, M. Lang, S. Y. Huang, J. Conklin, L. L. Wald, and S. F. Cauley, “Motion guidance lines for robust data-consistency based retrospective motion correction in 2D and 3D MRI,” Magn. Reson. Med., 2023.

[7] A. Tabari, M. Lang, D. Polak, D. N. Splitthoff, B. Clifford, W.-C. Lo, L. L. Wald, S. F. Cauley, O. Rapalino, P. Schaefer, J. Conklin, and S. Y. Huang, “Clinical evaluation of scout accelerated motion estimation and reduction (SAMER),” AJNR, 2022.

Figures