1830

Multislice-to-volume Prospective Motion Correction for Functional MRI Protocols at 7T1Imaging Centre of Excellence, University of Glasgow, Glasgow, Scotland, 2Fraunhofer Institute for Digital Medicine MEVIS, Bremen, Germany

Synopsis

Keywords: Motion Correction, fMRI, Prospective motion correction; Markerless; Real-time

7 Tesla MRI provides higher signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) and spatial resolution, but is also more sensitive to motion-induced artefacts. The restricted environment within 7T scanners make non-hardware options for motion correction attractive. In this abstract, we investigate the use of the markerless, image-based, real-time Multislice Prospective Acquisition Correction (MS-PACE) technique for functional MRI protocols at 7T. This multislice scheme allows for a sub-TR motion detection and correction. It is demonstrated that the technique is able to correct longer-term motion components occurring during the acquisition.Introduction

Ultra-high field MRI, such as 7 Tesla, has higher inherent signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) than standard clinical field strengths. However, this potential for higher resolution makes it more sensitive to motion-induced ghosting and blurring artefacts even to very small movements. This is especially pronounced in longer acquisitions, where the effects of involuntary motion are more visible [1]. Functional MRI (fMRI) protocols typically feature long acquisitions and high resolutions, and thus are prone to motion artefacts , which are typically corrected with retrospective motion correction [2]. Prospective motion correction can be performed to reduce these effects further [3]. The restricted environment in 7T scanners (i.e. narrower bores, tighter head coils) makes markerless, non-hardware techniques an attractive choice. In this abstract, we propose an implementation of the markerless, image-based, real-time Multislice Prospective Acquisition Correction (MS-PACE) technique for 7T functional MRI (fMRI). This method has previously been implemented for fMRI at 3T [4]. The 7T implementation also includes the use of the parallel imaging technique, in-plane generalised autocalibrating partially parallel acquisitions (GRAPPA) [5]. This technique helps to reduce spatial distortion effects in EPI that are more pronounced in 7T [6]. MS-PACE [7] is a prospective motion correction technique adapted from Prospective Acquisition CorrEction (PACE). In-plane and through-plane motion are estimated by registering a small number of equidistant 2D-echo-planar imaging slices (EPI multislice subset) to a reference volume, differing from PACE which uses whole volumes [8]. By using multislice-to-volume registration, sub-TR motion detection and thus a faster rate of update of the system can be performed.Methods

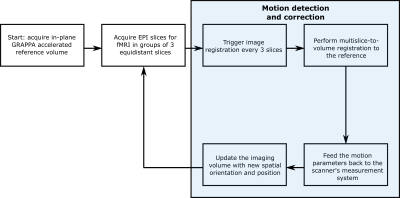

The validation study was performed in a MAGNETOM Terra 7T scanner (Siemens Healthineers, Erlangen, Germany) with a single-transmit, 32-channel receive head coil (Nova Medical, Wilmington, MA, USA) using an in-house-developed EPI sequence on a 23-year-old healthy volunteer. The scan protocol consisted of two acquisitions, without and with MS-PACE motion correction. The subject was blinded to the acquisition order. Each multislice subset used for registration had 3 slices. Beside the motion correction, the scan parameters for both scans were identical: voxel size 2×2×2mm3, resolution 96×96, GRAPPA factor 3, 60 slices, 100 volumes, echo spacing 580ms, TR 7s, TE 18ms and total acquisition time 12m1s. Figure 1 shows how the motion detection and correction pipeline operates. Calculated motion parameters are then fed back to the scanner system and the imaging gradients are subsequently updated to account for the preceding movements. Rigid body motion parameters (translation and rotation in x, y and z axes) were also retrospectively calculated using the multislice-to-volume method. Online and offline processing was done within the Image Calculation Environment (Siemens Healthineers, Erlangen, Germany) using InsightToolkit (ITK) open-source image registration libraries.Results and discussion

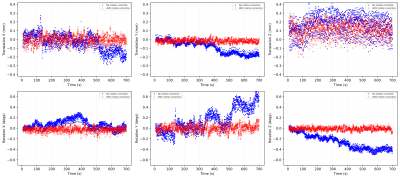

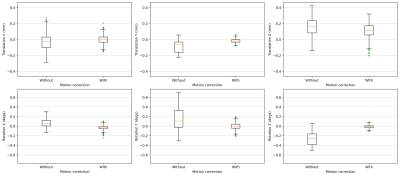

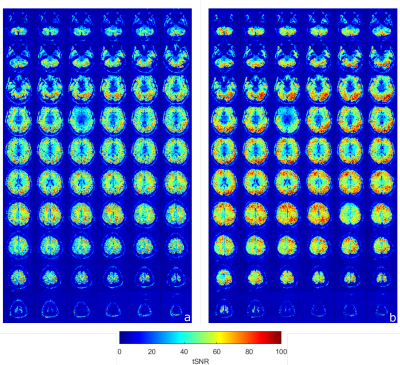

Figure 2 shows the comparisons of the retrospectively-calculated rigid-body motion parameters from both acquisitions. As seen in the motion parameter estimates for the acquisition without motion correction, the volunteer was subject to longer-term motion, which increased as the scan progressed. Figure 2 also shows how the motion parameters after prospective motion correction are closer to zero, indicating successful motion detection and real-time adjustment of the imaging volume. It is also observed in Figure 2 and 3 that there’s a higher variance in the through-plane motion parameters (translation Z, rotation X and Y) compared to the in-plane ones (translation X and Y, rotation Z). Figure 3, a box plot comparison of the motion parameters, also demonstrates this effect. This is due to the through-plane resolution’s dependence on the number of slices [9]. Figure 4 shows voxelwise temporal SNR (tSNR) maps for each slice, with and without motion correction. These maps illustrate the temporal variance in noise and were calculated by comparing the mean signal of each voxel to its standard deviation over the time series. The maps demonstrate an improvement in voxelwise tSNR in the acquisition with motion correction, noting that no retrospective motion correction was applied to either dataset.The 7T implementation has the limitation of a feedback lag of 350-700ms, relatively long compared to the previous implementation at 3T. In a future implementation, simultaneous multislice (SMS) imaging [4][10] will be implemented in the sequence to enable faster acquisition of the multislice navigators and thus a higher temporal resolution of motion correction. Another potential area of improvement is the image registration pipeline, including parallelisation of the ITK modules used for image registration [4]. Despite this, it has been possible to demonstrate that the technique can correct for longer-term motion components with EPI at 7T by incorporating in-plane GRAPPA to minimise spatial distortion. A sub-TR (up to 5% of TR) correction rate was achieved.

Conclusion

This study has evaluated an implementation of multislice-to-volume prospective motion correction for fMRI protocols at 7T and shown that the technique can detect and reduce the effects of longer-term incidental motion during a long fMRI acquisition.Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful for the support of Matthias Günther from Fraunhofer Institute for Digital Medicine MEVIS.References

[1] Herbst M et al. Reproduction of motion artifacts for performance analysis of prospective motion correction in MRI. Magn Reson Med. 2014;71:182-90.

[2] Maknojia S et al. Resting state fMRI: Going through the motions. Front Neurosci. 2019;13:1-13.

[3] Zaitsev M et al. Prospective motion correction in functional MRI. Neuroimage. 2017;154.

[4] Hoinkiss DC et al. Prospective motion correction in functional MRI using simultaneous multislice imaging and multislice-to-volume image registration. Neuroimage. 2019;200:159-73.

[5] Griswold MA et al. Generalized autocalibrating partially parallel acquisitions (GRAPPA). Magn Reson Med. 2002;47:1202-10.

[6] Speck O et al. High resolution single-shot EPI at 7T. Magn Reson Mater Phys. 2008;21:73-86

[7] Hoinkiss DC, Porter DA. Prospective motion correction in 2D multishot MRI using EPI navigators and multislice-to-volume image registration. Magn Reson Med. 2017;78:2127-35.

[8] Thesen S et al. Prospective Acquisition Correction for head motion with image-based tracking for real-time fMRI. Magn Reson Med. 2000;44:457-65.

[9] Winata S et al. Navigator Parameter Optimisation for MS-PACE Prospective Motion Correction. British & Irish Chapter of ISMRM Annual Meeting, 13-17 September 2021.

[10] Barth M et al. Simultaneous multislice (SMS) imaging techniques. Magn Reson Med. 2016;75:63-81.

Figures