1826

Severe MR Motion Artefact Correction with 2 step Deep Learning-based guidance1Pattern Recognition Lab, Friedrich-Alexander-University Erlangen-Nuremberg, Erlangen, Germany, 2Siemens Healthcare GmbH, Erlangen, Germany, 3Siemens Medical Solutions, Boston, MA, United States, 4Siemens Healthcare Gmbh, Erlangen, Germany, 5Department of Radiology, Athinoula A. Martinos Center for Biomedical Imaging, Boston, MA, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Machine Learning/Artificial Intelligence, Motion Correction

Motion artifacts can pose a difficult challenge in the clinical workflow. For addressing this issue, we here investigate the performance of two Deep Learning based motion mitigation strategies, MoPED and NAMER, and demonstrate that both approaches can readily be combined. This allows for the correction of severely corrupted images.Introduction

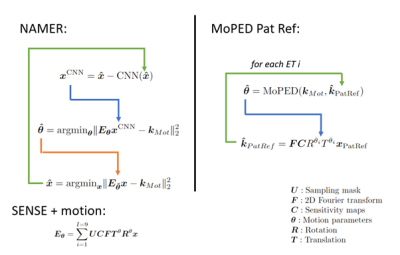

Motion artifacts in MRI are a inevitable problem which can cost up to 300,000$ per scanner and year1. Especially severe motion cases, unusable for diagnosis, which affect up to 19.8% of all neuroimaging scans2, are difficult to correct retrospectively. In this work we investigate how two competitive Deep Learning (DL)-based methods can be linked together to improve severe motion cases: NAMER3 and MoPED4 .Both methods avoid image alternations like hallucination (often observed in pure image-to-image networks5) by incorporating their Neural Network (NN) in a motion model-based optimization to preserve data consistency. NAMER incorporates a Neural Network (NN)-based motion-free image estimate in the optimization. On the other hand, MoPED estimates the motion parameters to a given reference in the k-space domain. As proposed at ISMRM 20226 the reference here is the Pat Ref scan, normally used to calculate the coil sensitivity map. Both motion correction algorithms are presented in Fig. 1. In this abstract, we compare NAMER and MoPED for multiple in-vivo cases with motion ranging from medium to severe. Furthermore, we demonstrate the benefits of combining both methods.

Methods

We used the data of6, which consists of 42 motion-free measurements of heads and phantoms in axial, sagittal and coronal orientation. The data was acquired with a T2-weighted Cartesian TSE with external Pat Ref scan (size 38 lines, 64 read-out values) using various Siemens MAGNETOM scanners (Siemens Healthcare, Erlangen, Germany) at 3 T. The Cartesian TSE samples 9 equidistant echo trains (ET) per slice with a turbo factor of 20 and an R=2 undersampling for a volume of 28 slices. For a supervised training of MoPED and NAMER the data was corrupted by simulating 2D motion.MoPED receives the corrupted k-space center crop with removed undersampling of 64x64 samples and the Pat Ref scan of a given slice. During training, the L2 loss between the simulated motion and the network output was minimized using ADAM. The architecture of MoPED is built from 4 DenseBlocks, compressing the input into a feature vector. This vector is mapped in a multi-task learning setting, i.e., one task per ET, into the motion parameters.

The NAMER network consists of 27 convolutional layer (CNN) and was trained to minimize the L2 loss between the motion-free images and the network output.

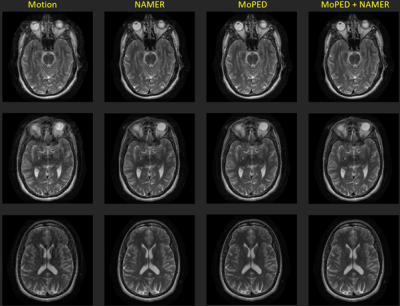

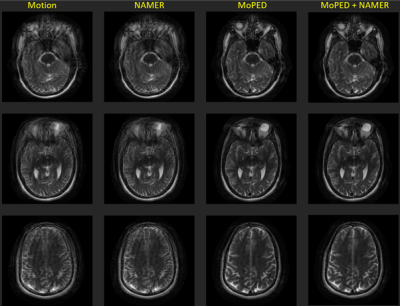

Three axial in-vivo volumes were acquired with deliberate head motion during the measurement. The instructions for the 3 scans were , 1) single head shake (rotation to one side for around 10 seconds) 2) a single rotation to one side after the half of the scan and 3) a free in-plane motion.

To correct these volumes, MoPED was iterated 5 times and NAMER 10 times. In the combined setting, NAMER was initialized by the image reconstruction and motion estimate of MoPED and ran for only 2 iterations.

Results

Fig. 2-4 show the results of the different reconstructions for the described motion patterns. The first column shows the motion images, the second column the NAMER result after 10 iterations, followed by the MoPED reconstruction with the iterative adaption of the Pat Ref scan. The last column depicts the results when NAMER is initialized with the MoPED results. The three rows show three different slice positions.Discussion and Conclusion

The results show that NAMER performs slightly better for medium motion cases, whereas MoPED can improve severely corrupted images. NAMER requires a good estimate of the uncorrupted image by the Neural Network as a starting point, which is not always possible for severe motion cases and thus results in a reduced performance. Medium motion cases can be restored using MoPED but might be limited by the motion estimate accuracy.Initializing NAMER with the MoPED results for a limited number of iterations refines the motion estimation. In case of severe motion this can even help NAMER’s CNN to predict an accurate motion-free image and thus overcome the convergence issues. The final image has a better image quality than using either method alone.

MoPED not only helps NAMER to converge, it also has the potential of greatly reducing NAMER's computation time. As MoPED uses the Pat Ref scan as motion-free reference, no optimizations are required throughout the MoPED algorithm and thus only relies on the fast motion estimate by MoPED.

Acknowledgements

No acknowledgement found.References

1 Slipsager JM, Glimberg SL, Søgaard J, et al. Quantifying the financial savings of motion correction in brain MRI: A model-based estimate of the costs arising from patient head motion and potential savings from implementation of motion correction. JMRI. 2020;52(3):731-738.

2 Andre JB, Bresnahan BW, Mossa-Basha M, et al. Toward quantifying the prevalence, severity, and cost associated with patient motion during clinical MR examinations. J Am Coll Radiol. 2015;12(7):689-695.

3Haskell MW, Cauley SF, Bilgic B, et al. Network Accelerated Motion Estimation and Reduction (NAMER): Convolutional neural network guided retrospective motion correction using a separable motion model. Magn Reson Med. 2019;82(4):1452-1461.

4 Hossbach J, Splitthoff D, Cauley S, et al. Deep Learning-Based Motion Quantification from k-space for Fast Model-Based MRI Motion Correction. Med Phy In print

5 Armanious K, Jiang C, Fischer M, et al. Medgan: Medical image translation using GANs. Magn Reson Med. 2020;79.

6 Hossbach J, Splitthoff D, Clifford B, et al. Think outside the box: Exploiting the imaging work ow for Deep Learning based motion estimation and correction. ISMRM 2022 #1952

Figures