1821

Effective removal of the residual head motion artifact after motion correction in fMRI data.1Radiology, Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, OH, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Motion Correction, Brain, Head motion, fMRI

We investigate the source of residual motion artifact after volumetric motion correction using a custom MR sequence acquisition with prospectively injected motion (SIMPACE). We injected various patterns of motion during scanning ex-vivo brain phantoms at 3T to synthesize head motion in an fMRI dataset. We propose voxelwise retrospective motion regressors in addition to 6 rigid body motion parameters, then compare it with the “standard” 6 motion parameters and their derivatives regressor models. The proposed model improves tSNR by 40% and 11% in linear drift of motion and the realistic motion case, respectively, compared to 6 motion parameter model.

Introduction

Head motion is largely considered to be the most dominant non-neuronal source, present in human fMRI data 1, 2. Since the residual motion artifact remains even after perfect volume motion 3, various methods have been proposed to utilize “retrospective motion regressors” which are regressed out after motion correction to attempt to ameliorate these residual effects of head motion 4-7. In this study, we investigate the source of the residual motion artifact using data from a custom MRI acquisition with prospectively injected motion and propose voxelwise motion regressor in addition to 6 rigid body motion parameters.Methods

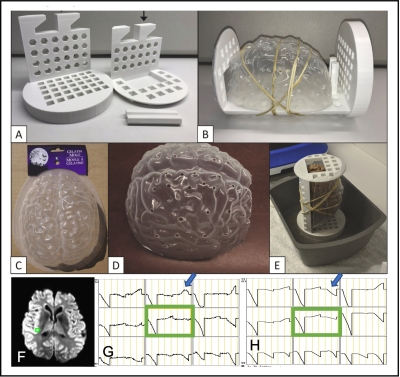

Ex-vivo brainWe built ex-vivo whole brain phantom 8, and scanned at 3T (see Fig1A-F).

MR acquisition

We modified Prospective Acquisition CorrEcted (PACE) EPI sequence 9 to inject the motion, referred as Simulated PACE (SIMPACE) sequence 5. Note that SIMPACE sequence alters the direction and amplitude of the gradient axes during the scanning, synthesizing inter-/intra-volume motion effect on the collected images. In this study, we only test inter-volume motion.

Using SIMPACE sequence (voxel size=2x2x4mm3, TR/TE=2s/28ms, 21 slices), we synthesized 3 different head motion patterns; A) impulse shift (4mm) in z-direction and rotation (4°) motion along x-/y-axes during 2s. B) linearly increasing shift and rotation (up to 4 mm/°) in x-/y-/z-direction during 60s. C) 10 realistic head motion cases, measured from 10 rs-fMRI HCP YA data using 3dvolreg, AFNI 10. Six rigid body motion parameters with 1/0.8s of sampling rate is interpolated to 2s of TR in SIMPACE.

Partial volume (PV) regressor

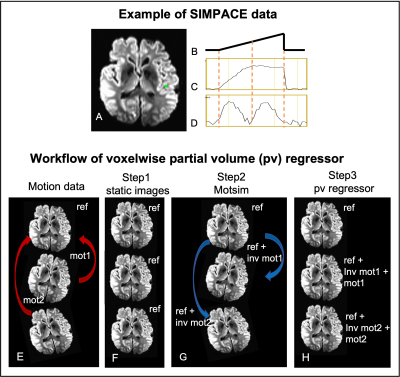

Fig2.A-D shows the example of SIMPACE B dataset. Y-directional drift of shift motion is injected up to 4mm, corresponding to 2 voxel shift, shown in Fig2.B. The time-series at a green voxel is plotted before (Fig2.C) and after (Fig2.D) motion correction. Note that the residual signal (Fig2.D) is bounded two times to 2mm of voxel dimension, which does not agree with the previous findings 3-7.

Volume motion is injected negatively on each static image to simulate the motion corrupted data, presented by Wilke 11. This simulated motion data is identical to “MotSim” in the previous work 12. Motsim is volume motion corrected to the reference, synthesizing the residual artifact. We use this output as voxelwise PV regressor. The workflow is displayed in Fig2.E-H.

Data analysis

All motion corrected SIMPACE data in this study is generated with known injected motion.

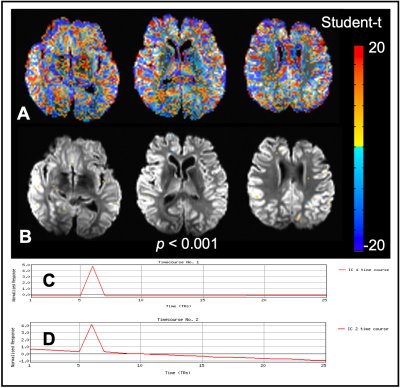

Dataset A: Student t-score maps are calculated on volume motion corrected SIMPACE data to the motion parameter (MoPa) and their derivative (Deriv). In addition, temporal ICA analysis is conducted 13.

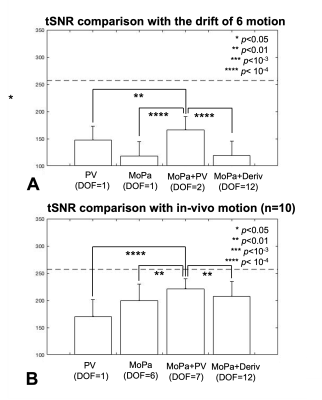

Datasets B and C: Temporal signal-to-noise ratio (tSNR) is calculated after volume motion correction and regress-out of 1) PV, 2) MoPa, 3) MoPa+PV and 4) MoPa+Deriv. Note that degree-of-freedom (DOF) of MoPa is 1 and 6 in B) and C) datasets, respectively. Averaged tSNR is reported in grey matter mask.

Results

Figure1.G shows the example of SIMPACE data with drift of z-axis rotational motion. Fig1.H plots the signal at the same voxel but generated by image post-processing. SIMPACE data is different with simply re-sampled data, as shown in blue arrows.The spin history effect is minimal with SIMPACE data of TR=2s. Impulse z-directional voxel shift alters the time interval of each slice acquisition with ± half of TR at 6th and 7th volumes, shown Fig3.B. ICA analysis does not detect the spin history effects either, as shown in Fig3.C and D.

The proposed PV regressor predicts the residual motion better than MoPa, resulting in tSNR with PV (147±26) and with MoPa (118±27) in the case of 6 linear drift motion cases, as shown in Fig4.A. The maximum tSNR is observed with 166±25 when MoPa+PV model is used. MoPa regressor model outperforms PV regressor in the case of realistic motion, resulting in 199±30 (MoPa) and 170±31 (PV) of tSNR. The maximum tSNR (222±18) is observed when MoPa+PV model is employed.

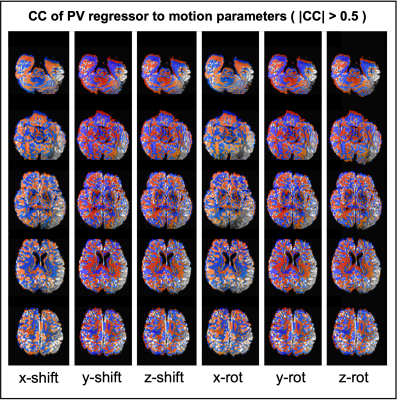

Figure 5 shows where PV regressor is highly correlated to rigid volume motion in the realistic motion case.

Discussion

While 6 rigid motion parameters have been used as effective motion regressor in fMRI analysis3 6, additional voxelwise displacement or its derivatives were proposed to remove the residual motion artifact 4, 5. Bullmore’s regressor model has 24 regressors and Beall’s model has 14. This study proposes single voxelwise regressor in addition to 6 rigid motion parameters. With the loss of single DOF, the proposed MoPa+PV model improves tSNR on average by 40% in the case of linear drift motion and 11% in the more realistic head motion cases.While PV regressor predicts the residual artifact after linear drift motion correction better than MoPa, MoPa regressors outperforms PV in realistic head motion SIMPACE data. It could be explained that the realistic head motion is continuous and random 7 and 6 DOF rigid motion parameter model more effectively removes the large variances than the single PV.

It should be noted that the standard deviation of tSNR with Mopa+PV model across 10 subjects is the smallest of 18, compared to other models (31, 30 and 30 in PV, MoPa and MoPa+deriv models), indicating that MoPa+PV model suppress the individual variation of residual motion even after the different pattern of head motions.

Acknowledgements

Authors acknowledge technical support by Siemens Medical Solutions.References

1. Hajnal JV, Myers R, Oatridge A, et al. Artifacts due to stimulus correlated motion in functional imaging of the brain. Magn Reson Med 1994;31:283-291

2. Hajnal JV, Saeed N, Oatridge A, et al. Detection of subtle brain changes using subvoxel registration and subtraction of serial MR images. J Comput Assist Tomogr 1995;19:677-691

3. Friston KJ, Williams S, Howard R, et al. Movement-related effects in fMRI time-series. Magn Reson Med1996;35:346-355

4. Bullmore ET, Brammer MJ, Rabe-Hesketh S, et al. Methods for diagnosis and treatment of stimulus-correlated motion in generic brain activation studies using fMRI. Hum Brain Mapp 1999;7:38-48

5. Beall EB, Lowe MJ. SimPACE: generating simulated motion corrupted BOLD data with synthetic-navigated acquisition for the development and evaluation of SLOMOCO: a new, highly effective slicewise motion correction. Neuroimage 2014;101:21-34

6. Johnstone T, Ores Walsh KS, Greischar LL, et al. Motion correction and the use of motion covariates in multiple-subject fMRI analysis. Hum Brain Mapp 2006;27:779-788

7. Power JD, Barnes KA, Snyder AZ, et al. Spurious but systematic correlations in functional connectivity MRI networks arise from subject motion. Neuroimage 2012;59:2142-2154

8. Kim S, Sakaie K, Blumcke I, et al. Whole-brain, ultra-high spatial resolution ex vivo MRI with off-the-shelf components. Magn Reson Imaging 2021;76:39-48

9. Thesen S, Heid O, Mueller E, et al. Prospective acquisition correction for head motion with image-based tracking for real-time fMRI. Magn Reson Med 2000;44:457-465

10. Cox RW. AFNI: software for analysis and visualization of functional magnetic resonance neuroimages. Comput Biomed Res 1996;29:162-173

11. Wilke M. An alternative approach towards assessing and accounting for individual motion in fMRI timeseries. Neuroimage 2012;59:2062-2072

12. Patriat R, Reynolds RC, Birn RM. An improved model of motion-related signal changes in fMRI. Neuroimage2017;144:74-82

13. Beckmann CF, DeLuca M, Devlin JT, et al. Investigations into resting-state connectivity using independent component analysis. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 2005;360:1001-1013

Figures

Fig2. The example of SIMPACE data after y-directional drift motion correction. The injected motion is shown in Fig2.B. Time series signals at a green voxel are presented before (C) and after motion correction (D). To synthesize the residual artifact, rigid volume motion is measured at each volume (E). After generating time-series of static images (F), motion is injected on static images to simulate motion data using inverse motion affine transformation matrix (G). Motion simulated data (Motsim) is motion corrected and proposed as voxelwise partial volume regressor (H).