1820

Prospective Motion Correction for 3D-EPI fMRI using Orbital Navigators and Linear Regression1Institute for Biomedical Engineering, ETH Zurich and University of Zurich, Zürich, Switzerland

Synopsis

Keywords: Motion Correction, fMRI (resting state)

We propose to apply a navigator-based prospective motion correction method to 3D-EPI fMRI scans. The method is investigated during in-vivo volunteer experiments with and without intentional motion. Post-processing with SPM12 shows that head motion is largely compensated by the navigator method. We show that the technique is sensitive to breathing motion and cardioballistic motion by comparing to physiological measurements from a breathing belt and pulse oximeter, and we show that it strongly reduces inter-volume displacements.Introduction

Head motion represents a major confounding factor in functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI).1 When analyzing fMRI time series, it is assumed that each voxel contains the same location in the brain over time. Since this assumption is usually violated due to involuntary head movements, image volumes are commonly registered to a reference volume prior to time series analysis. Intra-stack (2D multi-slice) and intra-volume (3D) motion within the volume TR, however, remains uncorrected by volumetric registrations.Prospective motion correction, on the other hand, realigns the scan volume to the moving head of the subject in real-time. It is therefore able to correct for motion on a finer timescale.2 In this work, we propose to apply a navigator-based prospective motion correction method3 to 3D-EPI scans. We investigate this method in in-vivo experiments.

Methods

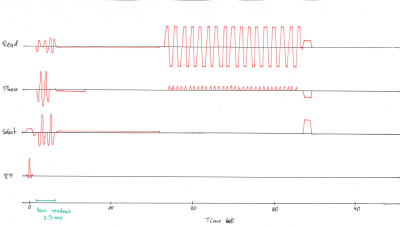

Resting-state functional images of two subjects were acquired using a 3D-EPI sequence (FOV=200x200x120mm, Resolution=2x2x2mm, Flip angle=13.8°, 100 dynamics, 3:37min., TE=25ms, TR=56ms, TRvol=2s, Readout/Phase/Select directions: RL/AP/HF) at a 7T Philips Achieva scanner (Philips Healthcare, Best, Netherlands) using a 32-channel head coil. Informed consent was attained, according to the rules of the institution. An orbital navigator readout was inserted into the sequence after the slab-selective excitation, as depicted in Figure 1. Head motion was estimated every TR=56ms using the algorithm presented in Ref. 3, and the motion estimates were used to realign the scan volume with the subject’s head in real-time.The scan was performed twice, once with and once without prospective motion correction. The volunteer was asked to perform a reproducible head rotation at half the scan duration, i.e., after 50 dynamics. This motion event consisted of rotations and translations in the range of up to 1.5 degrees and 2.5 millimeters and was reproduced similarly in both scans. Images were reconstructed using the vendor-provided image reconstruction.The SPM12 (Statistical Parametric Mapping) toolbox4 was used to calculate realignment parameters of the imaging volumes relative to the first dynamic.

During another scan (which lasted 300 dynamics instead of 100), the volunteer was asked to hold his head still. Physiological data was acquired during the scan using a breathing belt and a pulse oximeter. The head motion estimates from the orbital navigator are compared to the breathing curves and cardiac events hereinbelow.

Results

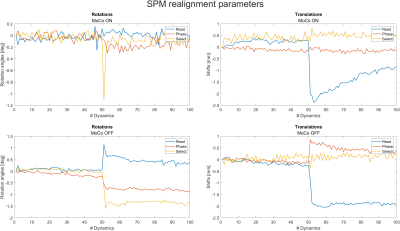

Figure 2 shows the realignment parameters estimated using SPM12. When prospective motion correction was activated, the realignment parameters were significantly smaller than without motion correction. The only exception is the translation in readout direction, where no change is noticeable between scans with and without motion correction.Figure 3 shows the first and last dynamic of the fMRI imaging sequence, as well as the difference image. Clearly, when motion correction is switched on, the difference between the first and last image is smaller, but as expected from the realignment parameters, some residual difference remains.

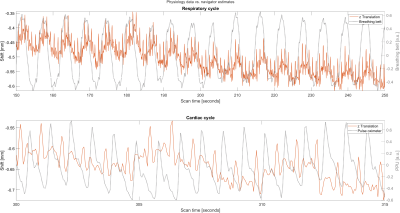

Figure 4 shows a 100-second and a 15-second excerpt from the z translations estimated by the orbital navigator during the scan, where the volunteer tried to hold still. Physiological data generated by the breathing belt and the pulse oximeter is overlayed. The motion curves from the navigator exhibit a slow oscillation, which is in sync with the breathing belt data, as well as sharp peaks at the cardiac frequency.

Discussion

The proposed method was able to correct for most of the volunteer's head motion in real-time by realigning the imaging slab to the volunteer's head. SPM12 only needed to estimate residual displacement, which was not addressed by the motion correction pipeline. Therefore, the realignment parameters were significantly smaller when motion correction was switched on. Translational displacement in readout direction was not reduced by the current implementation of this method. This requires further investigation.Since image realignment methods can only register whole image volumes to each other, their time resolution is effectively limited to the Volume-TR of 2 seconds. In contrast, the proposed motion correction method can also mitigate intra-volume effects, since it is evaluated every TR=56ms. We have shown that the navigator is sensitive to head motion stemming from breathing and heartbeat. With prospective correction, head motion caused by breathing can be compensated, thus reducing an important confounding factor in fMRI signal analysis. For motion which stems from heartbeat, the processing delay of about 200 ms is a limiting factor of the current method.

Conclusion

We have shown that the proposed method is able to prospectively correct for intra-volume and inter-volume head motion. It therefore improves data consistency during an fMRI acquisition by mitigating the confounding effects of bulk head motion as well as head motion due to breathing.Acknowledgements

This work has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under grant agreement No. 885876 (AROMA project).References

- Van Dijk, K. R., Sabuncu, M. R., & Buckner, R. L. (2012). The influence of head motion on intrinsic functional connectivity MRI. Neuroimage, 59(1), 431-438.

- Zaitsev, M., Akin, B., LeVan, P., & Knowles, B. R. (2017). Prospective motion correction in functional MRI. Neuroimage, 154, 33-42.

- Ulrich, T., Riedel, M., & Pruessmann, K. (2022). Prospective head motion correction using orbital k-space navigators and a linear perturbation model. In Proceedings of the 30th annual meeting of ISMRM.

- Penny, W. D., Friston, K. J., Ashburner, J. T., Kiebel, S. J., & Nichols, T. E. (Eds.). (2011). Statistical parametric mapping: the analysis of functional brain images. Elsevier.

Figures

First and last image of the fMRI imaging scan, as well as their difference images.

Upper row: Images from a scan with prospective motion correction.

Bottom row: Images from a scan without prospective motion correction.

The image difference is greatly reduced when motion correction is switched on.

Red: Raw z translation estimated by the orbital navigators. Gray: Physiological data from the breathing belt and pulse oximeter, respectively.

The navigator curves exhibit oscillations which are in sync with the breathing belt data, as well as sharp peaks at the same frequency as the heartbeat measured by the pulse oximeter.

The constant-time shift between the peaks from the pulse oximeter and the peaks from the navigator is probably caused by the cardiovascular timing differences due to the navigator measuring head motion, while the pulse oximeter sticks to the volunteer's finger.