1818

Self-supervised contrastive learning for motion artifact detection in whole-body MRI: Quality assessment across multiple cohorts1Medical Image and Data Analysis (MIDAS.lab), Department of Diagnostic and Interventional Radiology, University Hospital of Tuebingen, Tuebingen, Germany, 2Siemens Healthineers, Erlangen, Germany, 3Department of Diagnostic and Interventional Radiology, University of Freiburg, Freiburg, Germany, 4Max Planck Institute for Intelligent Systems, Tuebingen, Germany

Synopsis

Keywords: Machine Learning/Artificial Intelligence, Motion Correction, Motion Detection, Self-Supervised Learning

Motion is still one of the major extrinsic sources for imaging artifacts in MRI that can strongly deteriorate image quality. Any impairment by motion artifacts can reduce the reliability and precision of the diagnosis and a motion‐free reacquisition can become time‐ and cost‐intensive. Furthermore, in large-scale epidemiological cohorts, manual quality screening becomes impracticable. An automated quality assessment is thus of interest. Reliable motion estimation in varying domains (imaging sequences, multiple scanners, sites) is however challenging. In this work, we propose an attention-based transformer that can detect motion in various MR imaging scenarios.Introduction

MRI offers a broad variety of imaging applications with targeted and flexible sequence and reconstruction parametrizations. Varying acquisition conditions and long examination times make MRI susceptible to imaging artifacts, amongst which motion is one of the major extrinsic factors deteriorating image quality.Images recorded for clinical diagnosis are often inspected by a human specialist to determine the achieved image quality which can be a time-demanding and cost-intensive process. If insufficient quality is determined too late, an additional examination may be even required decreasing patient comfort and throughput. Moreover, in the context of large epidemiological cohort studies such as UK Biobank (UKB)1 or German National Cohort (NAKO)2 the amount and complexity exceed practicability for a manual image quality analysis. Thus, in order to guarantee high data quality, arising artifacts need to be detected as early as possible to seize appropriate countermeasures, as e.g. prospective3,4 or retrospective correction techniques5,6. Retrospective deep-learning correction methods7-14 have also been proposed for motion-affected images. However, these methods are not always available and/or applicable. Instead of a manual screening by experts or a retrospective correction, an automatic processing for an early prospective quality assurance can be a better suited alternative.

Ideally, a database of multiple pairwise motion-free and motion-affected images, or large cohorts with manually annotated datasets for motion artifact presence, would enable the use of supervised training procedures. Creation of these cohorts is very demanding with limited number of labeled samples. Most previous works worked within this context15-20 or simulated motion artifacts21-24.

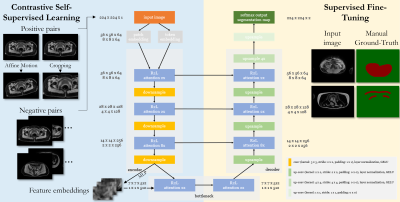

We propose a self-supervised model being capable to detect MR motion artifacts in various imaging domains. The proposed architecture combines a Region Vision Transformer (ViT) and Swin UNet which was trained on unlabeled data in a self-supervised contrastive fashion. The learned feature embedding is then fine-tuned on few labeled cases. The proposed framework is tested on abdominal data from UKB, NAKO, and two whole-body in-house acquired databases.

Methods

The proposed framework is depicted in Fig.1 and detects motion artifacts on a pixel level in various imaging domains (scanners, imaging sites, imaging sequences, contrasts).Data: Data was considered from four databases:

NAKO/UKB: Axial abdominal data was acquired with 3D Dixon in NAKO (3T Siemens Skyra,resolution=1.4x1.4x3mm3, TE/TR=1.23,2.46/4.36ms, α=9°) and UKB (1.5T Siemens Aera,resolution=2.2x2.2x4mm3, TE/TR=2.39,4.77/6.69ms, α=10°). 5000 randomly selected subjects were taken respectively.

MRMotion: Axial T1w and T2w fast-spin-echo data was recorded in head, abdomen and pelvis on 3T PET/MR (Siemens Biograph mMR) in 20 healthy subjects20. Each subject was scanned twice in a motion-free and motion-affected setting (head movement and free-breathing).

BLADE: Axial abdominal and pelvic data was acquired with T2w BLADE (resolution=0.9x0.9x4mm3, TE/TR=104/7560ms, α=130°) on a 1.5T MRI (Siemens Aera) in 420 patients.

Network: The ViT-UNet architecture consists of a Region-ViT25 and Swin UNet26. It takes as input a 2D image slice and encodes the local (patch) and regional (4x4 neighbourhood) tokens via convolution operations. These embeddings are passed through an R2L-attention block consisting of local and regional multi-head self-attention modules followed by a feed-forward network. In the encoder, downsampling is realized by 3x3 convolution with stride 2x2, layer normalization and Gaussian Error Linear Unit (GELU). In the decoder, upsampling consists of 2x2 transposed convolutions (stride 2x2), layer normalization and GELU.

Training: 2D slices were patched to a common size of 224x224 by sliding window (90% overlap) and normalized to unit variance. Random cropping, flipping and affine motion simulation (translation, rotation, shearing) provides the positive and negative pairs for the contrastive learning. The network is trained in a self-supervised manner for 60 epochs with AdamW optimizer (weight decay 1E-4), one-cycle learning rate scheduler (1E-6 to 1E-4), batch size 64, and an L1-similarity loss between input and reconstructed output, and a contrastive loss on the bottleneck features. For SSL training, 4980 subjects (NAKO, UKB respectively), and 415 (BLADE) were taken. Afterwards, the encoder was frozen and the feature embeddings were used for supervised fine-tuning on 15 (NAKO, UKB) and 15 (MRMotion) with manually annotated motion masks and binary cross-entropy loss.

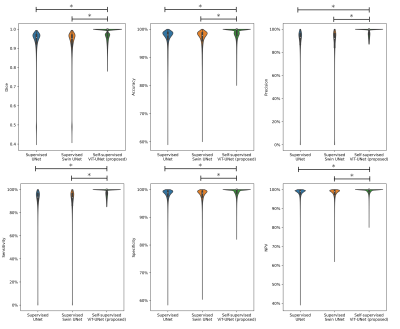

Experiments: Performance is compared to vanilla UNet and Swin UNet trained fully-supervised and self-supervised Swin UNet on 200 annotated cases and tested for 20 subjects (uniform drawn over databases) with manual annotations in terms of accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, precision, negative-predictive-value and Dice.

Results and Discussion

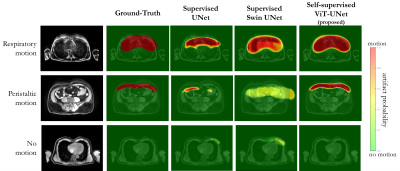

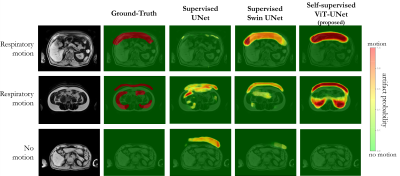

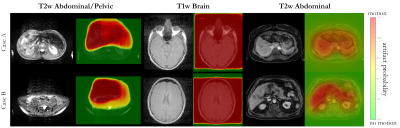

Fig.2 and 3 depict exemplary subject slices from the NAKO and UKB for the different architectures. Fig.4 shows the performance for the proposed architecture over the different databases. The metrics are illustrated in Fig.5. Overall, the proposed approach can reliably detect motion. Self-supervised contrastive learning outperforms supervised training. While, some pixel-wise discrepancies exist between network and manual annotation, they could also be attributed to ambiguities in labelling.We acknowledge several limitations. Databases need to be harmonized with respect to sample size and composition. Further investigations are needed to verify the reliability of the proposed approach in more diverse imaging scenarios. Other means of assessing the model accuracy and measuring the existence of motion are needed.

Conclusion

The proposed framework was self-supervised trained on unlabeled data and fine-tuned on a few labeled cases. It can reliably detect motion artifacts in multiple cohorts without the need for retraining, making it suitable to operate as an automatic quality control.Acknowledgements

This project was conducted with data from the German National Cohort (GNC) (www.nako.de). The GNC is funded by the Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) (project funding reference no. 01ER1301A/ B/C and 01ER1511D), federal states, and the Helmholtz Association, with additional financial support from the participating universities and institutes of the Leibniz Association. We thank all participants who took part in the GNC study and the staff in this research program.

This work was carried out under UK Biobank Application 40040. We thank all participants who took part in the UKBB study and the staff in this research program.

The work was funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation) under Germany’s Excellence Strategy – EXC 2064/1 – Project number 390727645.

References

1. Ollier et al. UK Biobank: from

concept to reality. Pharmacogenomics 2005;6(6):639-646.

2. Bamberg et al. Whole-Body MR Imaging

in the German National Cohort: Rationale, Design, and Technical Background. Radiology

2015;277(1):206-220.

3. Maclaren et al. Prospective motion

correction in brain imaging: a review. Magn Reson Med 2013;69(3):621-636.

4. Zaitsev et al. Motion artifacts in

MRI: A complex problem with many partial solutions. J Magn Reson Imaging 2015;42(4):887-901.

5. Atkinson et al. An autofocus

algorithm for the automatic correction of motion artifacts in MR images. Information Processing in Medical Imaging; 1997;

Berlin, Heidelberg. Springer Berlin Heidelberg. p 341-354. (Information Processing in Medical Imaging).

6. Odille et al. Generalized

reconstruction by inversion of coupled systems (GRICS) applied to

free-breathing MRI. Magn Reson Med 2008;60(1):146-157.

7. Haskell et al. Network Accelerated

Motion Estimation and Reduction (NAMER): Convolutional neural network guided

retrospective motion correction using a separable motion model. Magnetic

Resonance in Medicine 2019:mrm.27771-mrm.27771.

8. Johnson et al. Conditional

generative adversarial network for 3D rigid‐body motion correction in MRI. Magnetic

Resonance in Medicine 2019:mrm.27772-mrm.27772.

9. Küstner et al. Retrospective

correction of motion-affected MR images using deep learning frameworks.

Magnetic Resonance in Medicine 2019;82(4):1527-1540.

10. Lee et al. MC2-Net: motion correction

network for multi-contrast brain MRI. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine

2021;86(2):1077-1092.

11. Levac et al. Accelerated Motion

Correction for MRI using Score-Based Generative Models. arXiv 2022(2211.00199).

12. Sommer et al. Correction of Motion

Artifacts Using a Multiscale Fully Convolutional Neural Network. AJNR American

journal of neuroradiology 2020;41(3):416-423.

13. Usman et al. Motion Corrected

Multishot MRI Reconstruction Using Generative Networks with Sensitivity

Encoding. 2019.

14. Tamada et al. Motion Artifact

Reduction Using a Convolutional Neural Network for Dynamic Contrast Enhanced MR

Imaging of the Liver. Magn Reson Med Sci 2020;19(1):64-76.

15. Fantini et al. Automatic detection of

motion artifacts on MRI using Deep CNN. 2018. p 1-4.

16. Lorch et al. Automated Detection of

Motion Artefacts in MR Imaging Using Decision Forests. Journal of Medical

Engineering 2017;2017:1-9.

17. Romero Castro et al. Detection of MRI

artifacts produced by intrinsic heart motion using a saliency model. In: Brieva

J, García JD, Lepore N, Romero E, editors; 2017 2017/11//. SPIE. p 51-51.

18. Meding et al. Automatic detection of

motion artifacts in MR images using CNNS. 2017 5-9 March 2017. p 811-815.

19. Iglesias et al. Retrospective Head

Motion Estimation in Structural Brain MRI with 3D CNNs. Springer, Cham;

2017. p 314-322.

20. Küstner et al. Automated

reference-free detection of motion artifacts in magnetic resonance images.

Magnetic Resonance Materials in Physics, Biology and Medicine

2018;31(2):243-256.

21. Oksuz et al. Automatic CNN-based

detection of cardiac MR motion artefacts using k-space data augmentation and

curriculum learning. Medical Image Analysis 2019;55:136-147.

22. Jangâ et al. Automated MRI k-space

Motion Artifact Detection in Segmented Multi-Slice Sequences. 2022. p 5015.

23. Haskell et al. TArgeted Motion

Estimation and Reduction (TAMER): Data Consistency Based Motion Mitigation for

MRI Using a Reduced Model Joint Optimization. IEEE Trans Med Imaging

2018;37(5):1253-1265.

24. Oh et al. Unpaired MR Motion Artifact

Deep Learning Using Outlier-Rejecting Bootstrap Aggregation. IEEE Trans Med

Imaging 2021;40(11):3125-3139.

25. Chen et al. Regionvit:

Regional-to-local attention for vision transformers. arXiv preprint

arXiv:210602689 2021.

26. Cao et al. Swin-unet:

Unet-like pure transformer for medical image segmentation. arXiv preprint

arXiv:210505537 2021.

Figures