1809

A fat quantification approach based on longitudinal relaxation time

Yanglei Wu1, Xiaoyue Zhou2, Ke Xu3, and Huayan Xu3

1MR Collaboration, SIEMENS Healthineers Ltd., Beijing, China, 2MR Collaboration, SIEMENS Healthineers Ltd., Shanghai, China, 3Department of radiology, West China Second University Hospital, Chengdu, China

1MR Collaboration, SIEMENS Healthineers Ltd., Beijing, China, 2MR Collaboration, SIEMENS Healthineers Ltd., Shanghai, China, 3Department of radiology, West China Second University Hospital, Chengdu, China

Synopsis

Keywords: Quantitative Imaging, Fat

The quantification of fat in humans is plays an important role in clinical diagnosis and scientific research. Especially in some cardiomyopathy characterized by fat deposition like arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy, and duchenne muscular dystrophy-associated cardiomyopathy. Current magnetic resonance imaging-based fat quantification methods have difficulty to characterizing cardiac etc. fat fractions. But the application of cardiac T1 mapping has been very extensive, and our proposed approach to build a partial volume model to utilize the T1 value of voxel obtained by T1 mapping can complete the measurement of cardiac fat content.Introduction

Adipose tissue is found in various body tissues, such as subcutaneous fat, intermuscular space, and bone marrow. If there are excess fat deposits in the liver, heart, and other organs, their functions will be affected and people's health will be threatened. Fat quantifying can helps us monitor health conditions and diagnose diseases. Biopsy is the gold standard for quantifying fat content, but is limited due to its invasiveness. Nowadays, non-invasive imaging methods such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can provide tissue fat quantification information, which can be used as an alternative. The Multi-echo Dixon approach is often used for fat quantification in statistical organs1,2. However, it occasionally fails to correctly separate the water and fat due to improper parameters settings and/or the patient’s motion during the scan. Besides, it cannot be applied to motion organs, such as the heart. We proposed a fat quantification method utilizing the distinguishable T1 values of fat and water, providing the proton density fat fraction (PDFF) based on any T1 maps derived by MRI.Theory

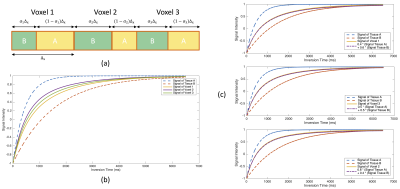

Longitudinal relaxation time (T1) is the experimental ‘spin-lattice relaxation time’. We can simulate the signal intensity of the tissue using the Bloch equation3, extended phase graph4, etc. approach by T1 value. As shown in Figure 1 (b), to reduce the complexity of the model, a simple exponential model proposed by Felix Bloch3 (equation (1)) is used to describe the signal intensity at different inversion times (TI).$$S=M_z=M_0(1-2*e^{-\frac{TI}{T1}}) \tag{1}$$

The partial volume model is shown in Figure 1 (a)5. The signal for voxel ith when point spread effects of the image reconstruction are neglected is the sum of the voxel signal contributions $$$\hat{\rho}_{A,i}$$$ and $$$\hat{\rho}_{B,i}$$$ from tissues A and B, respectively, i.e.,

$$\hat{\rho}_{voxel,i}=\hat{\rho}_{A,i}+\hat{\rho}_{B,i}\tag{2}$$

Now

$$\left\{\begin{matrix} \hat{\rho}_{A,i}=(1-\alpha_{i})*S_{A} \\ \hat{\rho}_{B,i}=\alpha_{i}*S_{B}\end{matrix}\right.\tag{3}$$

$$$S_{A}$$$ and $$$S_{B}$$$ represent the signal for tissues A and B, respectively, $$$\alpha_{i}$$$ is the fraction of voxel ith occupied by tissue B. The signal intensities of tissues A and B versus TI are shown in Figure 1 (b), and hence form equation (2):

$$\hat{\rho}_{voxel,i}=(1-\alpha_{i})*S_{A}+\alpha_{i}*S_{B}\tag{4}$$

Methods

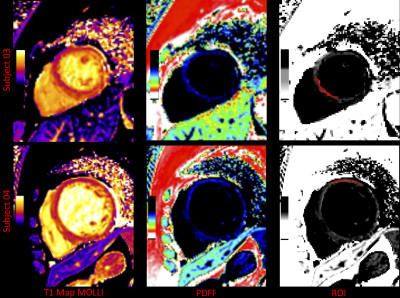

Based on the partial volume model, we modeled a voxel into two components, water (Tissue A) and fat (Tissue B). We set the T1 values of fat and water through empirical or experimental measurements, measured the T1 value of each voxel by T1 mapping, and used these T1 values to simulate the signal intensity curves of water, fat, and voxels (as shown in Figure 1(c)). As equation (4), the fat content ($$$\alpha_{i}$$$) in the voxel is fitted by the approximation algorithm.We recruited a total of four subjects for testing, including two healthy volunteers to test the mid-thigh muscles and two patients with Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy (DMD) with myocardial fat infiltration to test the myocardial fat fraction. We performed mid-thigh scans on a 3T scanner [MAGNETOM Vida, Siemens Healthcare, Erlangen, Gemany] including 6pt-Dixon, VFA T1 Mapping with voxel size 1*1*5 mm3. The cardiac native T1 mapping imaging was performed on a 3T scanner [MAGNETOM Skyra, Siemens Healthcare, Erlangen, Gemany] using a MOdified Look-Locker Inversion recovery (MOLLI) sequence with a 5b(3b)3b (b for heartbeat) scheme with breath-hold and with voxel size 1.6*1.6*6 mm3.

Results

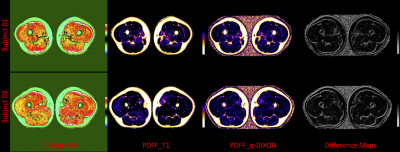

As shown in Figure 2, the PDFF calculated by longitudinal relaxation time and multi-echo Dixon is in good agreement in the mid-thigh muscle group of two healthy volunteers, and the PDFF of the former is slightly higher in the intermuscular space. Figure 3 shows the native T1 maps and PDFF maps of two patients with DMD. A T1 decrease was found in the short-axis view of both cases. The PDFF maps clearly showed diffuse fat decomposition of the myocardium. The PDFF in the septum of subject 03 and the PDFF in the free wall of subject 04 were 7.23% and 9.68%, respectively.Discussion

As shown in Figure 2 “Difference Maps”, the difference between the two methods appears in the position of the fascia. Perhaps the multi-echo Dixon underestimates the fat content of the fascia, or the “water fat shift” causes the approach based on longitudinal relaxation time to overestimate the fascia fat fraction. The proposed method can be used for myocardium fat quantification based on cardiac native T1 maps derived from routine clinical care. Compared to native T1 estimation, PDFF map provided direct fat fraction value which can be used for evaluating the progress of the diseases, such as DMD severity.Conclusion

Our proposed longitudinal relaxation time-based fat quantification approach has the same accuracy as multi-echo Dixon and can be used in areas where conventional MRI methods, such as cardiac tissue, cannot complete fat quantification. Various T1 mapping methods can use this approach to quantify fat, but the accuracy of quantification depends on the accuracy of voxel T1 value measurements. The fraction of fat and water can be obtained, and this method can also be used to solve the problem that water-fat separation cannot achieve under ultra-high fields. Therefore, it has a very high practical value in MRI fat quantification and water-fat separation.Acknowledgements

No acknowledgement found.References

1. Dixon W T. Simple proton spectroscopic imaging[J]. Radiology, 1984, 153(1): 189-194.

2. Hu H H, Börnert P, Hernando D, et al. ISMRM workshop on fat–water separation: insights, applications and progress in MRI[J]. Magnetic resonance in medicine, 2012, 68(2): 378-388.

3. Bloch F. Nuclear induction[J]. Physical review, 1946, 70(7-8): 460.

4. Weigel M. Extended phase graphs: dephasing, RF pulses, and echoes‐pure and simple[J]. Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging, 2015, 41(2): 266-295.

5. Brown R W, Cheng Y C N, Haacke E M, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging: physical principles and sequence design[M]. John Wiley & Sons, 2014.

Figures

Figure 1. (a) Model of a 1D voxel which is occupied by two different tissues with different fractions; (b) Signal intensity curves of Tissue A and B, Voxel 1, 2, 3; (c) Approximation of partial volume effect in voxel 1, 2, and 3 in (b)

Figure 2. Mid-thigh muscle fat quantification, “Difference Maps” is the percentage difference of subjects 01 and 02 between PDFF by longitudinal relaxation time and multi-echo Dixon.

Figure 3. Native T1 maps, PDFF maps, and region of interest (ROI) of two DMD patients. Myocardial PDFF of subjects 03 and 04 within the ROI was 7.23±3.29% and 9.68±2.52% (Mean±SD %), respectively.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.58530/2023/1809