1791

Quantitative analysis of the placental structure and function and fetal growth using intravoxel incoherent motion MRI1Sagol Brain Institute, Tel Aviv Sourasky Medical Center, Tel Aviv, Israel, 2The Department of Biomedical Engineering, Tel Aviv University, Tel Aviv, Israel, 3School of Computer Science and Engineering, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Jerusalem, Israel, 4Sackler Faculty of Medicine, Tel Aviv University, Tel Aviv, Israel, 5Department of Radiology, Tel Aviv Sourasky Medical Center, Israel, Tel Aviv, Israel, 6Division of Pediatric Radiology, Tel Aviv Sourasky Medical Center, Israel, Tel Aviv, Israel, 7Sagol School of Neuroscience, Tel Aviv University, Tel Aviv, Israel, 8Department of Maternal-Fetal Medicine and High Risk Pregnancy Outpatient clinic, Tel Aviv Sourasky Medical Center, Tel Aviv, Israel

Synopsis

Keywords: Quantitative Imaging, Perfusion, Intravoxel incoherent motion, IVIM

Placental structural and functional parameters are important for the assessment of placental insufficiency and fetal growth. Here we assessed quantitative measures of placental structural and functional parameters extracted from Intravoxel-incoherent motion (IVIM) with radiomics analysis, in fetuses with growth restriction (FGR) and appropriate for gestational age (AGA). Placental structure (volume and centricity index (CI, umbilical cord insertion location) were correlated with radiomics features of placental perfusion in AGA, and some were found to be significantly different between FGR and AGA, indicating higher functional heterogeneity in FGR. This multi-parametric quantitative placental assessment may improve identification of FGR fetuses.Introduction

The placenta is an essential organ for normal development of the fetus. Placental dysfunction is a leading cause of perinatal mortality and morbidity, is associated with short- and long-term consequences1 and frequently represented by fetal growth restriction (FGR). Clinical practice for fetal growth and placental assessment is based on ultrasound linear measurements and uterine artery Doppler ultrasound2, which provides only an indirect measurement of placental blood flow and cannot serve as a standalone biomarker for screening FGR fetuses3.Placental structural characteristics such as volume and umbilical cord insertion location were shown to be associated with placental function and fetal growth4–7. Placental functional parameters, assessed using advanced MRI methods including Intravoxel-incoherent motion (IVIM), were shown to be associated with gestational age (GA) in appropriate for gestational age (AGA) fetuses and to be reduced in cases with FGR8-10.

Yet, relations between placental structural and functional parameters, the functional heterogeneity as can be captured by radiomics approach, and their association with fetal growth required further investigation.

The objectives of this study were: (1) to comprehensively characterize placental structure and function using IVIM, with radiomics analysis; (2) to assess the association between placental characteristics and fetal growth in AGA fetuses; and (3) to assess differences in placental parameters between AGA and FGR fetuses.

Our hypothesis is that using a multi-parametric quantitative approach of the placental structure and function, can improve placental insufficiency assessment.

Methods

Subjects: A total of thirty-six women at late GA (30-38 weeks) were included in this study (mean GA=33.59±1.61, IRB approved). Twenty-five cases were considered as AGA (31-36 weeks) and eleven were diagnosed as FGR (30-38 weeks).MRI acquisition: Fetal MRI data were acquired using 3T Prisma (Siemens Healthineers). The scans consisted of: (1) T2-weighted (TRUFI) anatomical sequences, covering the entire placenta and fetus from which placental volume, total fetal volume and umbilical cord insertion location were extracted; (2) T2-weighted (TRUFI) fetal brain scan from which brain volume was extracted; (3) T2-weighted (TRUFI) anatomical sequences of the placenta, to define the volume of interest (VOI) of the placenta and (4) IVIM sequence with the same slice orientation and resolution, acquired with 7 b-values (0, 50, 100, 150, 400, 700, 1000 𝑠/𝑚𝑚2).

Image analysis:

Figure 1 illustrates the image analysis pipeline.

a. Placental structural assessment: placental volume was extracted from sequence (1), using automatic deep learning method11. Umbilical cord insertion location (centricity index (CI)), was manually quantified as the relative distance of the insertion location from the center of the placental disc, given as percentage of the placental radius12.

b. Placental functional assessment: IVIM parameters including perfusion fraction (f), diffusion coefficient (D) and pseudo-diffusion coefficient (D*) were estimated by fitting the IVIM bi-exponential model13. Placental VOI was segmented manually based on sequence (3). Mean values of f,D and D* were calculated for each placental VOI. 120 Radiomics features were extracted from the IVIM parameters maps using Pyradiomics14.

c. Fetal growth: fetal body and brain volumes were extracted from sequences (1) and (2) using automatic deep learning segmentation methods15.

Statistical analysis: Pearson's correlation was used to assess correlations between placental parameters and GA (in AGA fetuses); between placental structural and functional parameters; and between placental parameters and fetal growth.

Results and Discussion

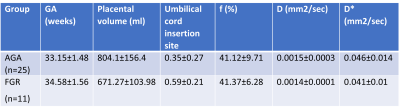

Placental assessment in AGA: No significant correlations were detected between structural (placental volume, CI) and functional (f,D,D*) parameters and GA, that may be explained by the small range of GA. Previous studies showed increased placental volume with GA, however GA range was much larger16. Regarding changes in functional parameters with GA, previous studies reported contradictory results, either increased10,17 or decreased perfusion18. Others showed no change in perfusion with GA19,20, as seen in our findings.Mean values of placental parameters of AGA fetuses are presented in Table 1.

Significant correlations were detected between placental volume and radiomics features derived from perfusion (f) maps and between CI and other radiomics features of f (p<0.05). These results indicate higher heterogeneity as CI is higher (more marginal).

No significant correlations were detected between any placental parameters and fetal growth, including the radiomics features.

Placental assessment in FGR: Mean values of placental parameters of FGR fetuses are presented in Table 1.

Significant correlations were detected between placental volume and perfusion parameter (f) radiomics features and between CI and other radiomics features of the perfusion parameter (p<0.05). Significant correlations were detected between

Differences between AGA and FGR:

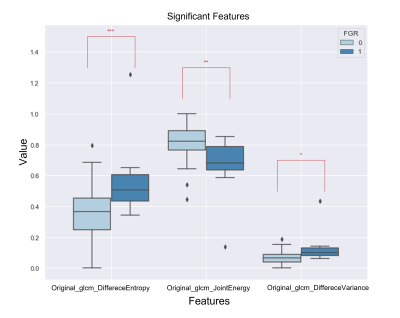

Placental volume was significantly smaller and CI was significantly higher (indicating more marginal cord insertion) in FGR placentas compared with AGA (p<0.05). No significant differences between groups were detected for IVIM parameters. This result is partially in contrast to other studies that found significant reduced f in FGR fetuses, yet no differences between groups for D,D*10. Several radiomics features derived from perfusion parameter were significantly different between groups (p<0.05), related to entropy, energy, and variance, which demonstrate higher heterogeneity in FGR placentas (Fig.2).

Conclusions

This study provides a multi-parametric quantitative functional and structural assessment of the placenta. This comprehensive assessment can improve identification of cases with placental insufficiency and may help to identify fetuses at high risk for FGR.Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Israel Innovation Authority.References

1. Gagnon, R. Placental insufficiency and its consequences. European Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology and Reproductive Biology 110, (2003).

2. Nardozza, L. M. M. et al. Fetal growth restriction: current knowledge. Arch Gynecol Obstet 295, 1061–1077 (2017).

3. Pedroso, M. A., Palmer, K. R., Hodges, R. J., Costa, F. da S. & Rolnik, D. L. Uterine artery Doppler in screening for preeclampsia and fetal growth restriction. Revista brasileira de ginecologia e obstetricia 40, 287–293 (2018).

4. Damodaram, M. S. et al. Foetal volumetry using magnetic resonance imaging in intrauterine growth restriction. Early Hum Dev 88, S35–S40 (2012).

5. O’Quinn, C., Cooper, S., Tang, S. & Wood, S. Antenatal diagnosis of marginal and velamentous placental cord insertion and pregnancy outcomes. Obstetrics & Gynecology 135, 953–959 (2020).

6. Link-Sourani, D. et al. Ex-Vivo MRI of the Normal Human Placenta: Structural-Functional Interplay and the Association With Birth Weight. J Magn Reson Imaging 56, 134–144 (2022).

7. Andescavage, N. et al. In vivo assessment of placental and brain volumes in growth-restricted fetuses with and without fetal Doppler changes using quantitative 3D MRI. J Perinatol 37, 1278–1284 (2017).

8. Capuani, S. et al. Diffusion and perfusion quantified by Magnetic Resonance Imaging are markers of human placenta development in normal pregnancy. Placenta 58, 33–39 (2017).

9. Caroline, H., Marianne, S., Astrid, P. & Anne, S. Placental diffusion-weighted MRI in normal pregnancies and those complicated by placental dysfunction due to vascular malperfusion. Placenta 91, 52–58 (2020).

10. Liu, X.-L., Feng, J., Huang, C.-T., Mei, Y.-J. & Xu, Y.-K. Use of intravoxel incoherent motion MRI to assess placental perfusion in normal and Fetal Growth Restricted pregnancies on their third trimester. Placenta 118, 10–15 (2022).

11. Specktor-Fadida, B. et al. A Bootstrap Self-training Method for Sequence Transfer: State-of-the-Art Placenta Segmentation in fetal MRI. Lecture Notes in Computer Science (including subseries Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence and Lecture Notes in Bioinformatics) 12959 LNCS, 189–199 (2021).

12. Link, D. et al. Placental vascular tree characterization based on ex-vivo MRI with a potential application for placental insufficiency assessment. Placenta 96, 34–43 (2020).

13. le Bihan, D., Breton, E. & Cueron, M. Separation of perfusion and diffusion in intravoxel incoherent motion (IVIM) imaging. in Book of abstracts: Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine (1986).

14. van Griethuysen, J. J. M. et al. Computational radiomics system to decode the radiographic phenotype. Cancer Res 77, e104–e107 (2017).

15. Fadida-Specktor, B. et al. Automatic Segmentation and Normal Dataset of Fetal Body from Magnetic Resonance Imaging. in ISMRM 2021 3887 (2021).

16. Andescavage, N. et al. In vivo assessment of placental and brain volumes in growth-restricted fetuses with and without fetal Doppler changes using quantitative 3D MRI. Nature Publishing Group (2017) doi:10.1038/jp.2017.129.

17. Jakab, A. et al. Microvascular perfusion of the placenta, developing fetal liver, and lungs assessed with intravoxel incoherent motion imaging. Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging 48, 214–225 (2018).

18. Sohlberg, S. et al. Magnetic resonance imaging-estimated placental perfusion in fetal growth assessment. Ultrasound in Obstetrics & Gynecology 46, 700–705 (2015).

19. Moore, R. J. et al. Spiral artery blood volume in normal pregnancies and those compromised by pre‐eclampsia. NMR in Biomedicine: An International Journal Devoted to the Development and Application of Magnetic Resonance In vivo 21, 376–380 (2008).

20. Derwig, I. et al. Association of placental perfusion, as assessed by magnetic resonance imaging and uterine artery Doppler ultrasound, and its relationship to pregnancy outcome. Placenta 34, 885–891 (2013).

Figures

Table 1: Mean values of structural and functional parameters of AGA and FGR fetuses.

Figure 1: Illustration of the image analysis pipeline – a. Placental structural assessment - placental volume and centricity index; b. Placental functional assessment - IVIM parameters and radiomics features; c. Fetal growth assessment. This pipeline is executed for both AGA and FGR groups and correlations in each group is assessed.

Figure 2: An example of 3 significant radiomics features derived from f parameter maps for AGA group (0) and FGR group (1).