1753

Arterial Spin Labeling in Cerebral Gliomas During Breath-Holding1Department of Radiology, Clinica Universidad de Navarra, Pamplona, Spain, 2IdiSNA, Instituto de Investigación Sanitaria de Navarra, Pamplona, Spain, 3Department of Anesthesia, Perioperative Medicine and Critical Care, Clinica Universidad de Navarra, Pamplona, Spain, 4Siemens Healthcare, Madrid, Spain

Synopsis

Keywords: Tumors, Perfusion, Breath Holding

PCASL was used to measure cerebral blood flow (CBF) in eighteen patients with high-grade gliomas (III and IV) during normal breathing followed by a breath-holding task (ten periods of 21s interleaved with periods of normal breathing) to assess baseline CBF and cerebrovascular reactivity (CVR). All patients completed the task successfully and CBF and CVR maps were generated. CBF ratio in contrast-enhanced tumor area was higher in grade IV than grade III gliomas, as expected. CVR in tumor areas was decreased compared to GM CVR values. More studies are needed to assess the CVR heterogeneity in tumoral tissue.Introduction

Elevated CO2 due to hypercapnia induces vasodilation which increases cerebral blood flow (CBF).1 The increase of CBF induce by hypercapnia, known as cerebrovascular reactivity (CVR), is an indicator of cerebrovascular health. Measurements of CVR have been typically assessed with the blood oxygen-level dependent (BOLD) technique2–5, but BOLD does not provide a direct measurement of CBF. Arterial Spin Labeling (ASL) can provide a quantitative measure of CBF and has been previously used to investigate changes in cerebrovascular hemodynamics induced by breath-holding in healthy volunteers.6Diffuse gliomas are believed to disrupt the perivascular organization.7–9 Therefore, the CVR coupling mechanism in cerebral tumors is compromised leading to neurovascular uncoupling10, which refers to the breakdown of the normal neurovascular-coupling cascade.11 The goal of this work was to study eighteen patients with high-grade gliomas while doing breath-holds, which are robust enough to induce CVR due to elevation of CO2.5 We assessed differences in the response to hypercapnia in the normal brain tissue and glioma; in the different areas within the glioma; and between different grades of tumor.Methods

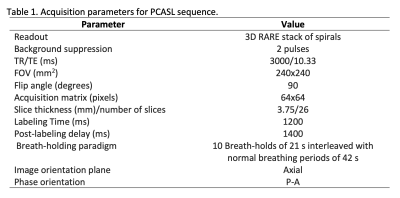

The protocol was approved by the institutional research committee and written informed consent was obtained. A total of eighteen patients (12 male, mean age 54.44, SD=10.73, range 31-81 years-old) with newly diagnosed and untreated brain diffuse glioma (WHO Grade III or IV12, confirmed by histopathological diagnoses) were scanned in a 3T Siemens Skyra MRI scanner, with a 32-channel head coil, using a PCASL sequence. Other anatomical images were acquired, according to clinical protocol. PCASL acquisition parameters are presented in Figure 1. 260 control and label images were acquired while patients were asked to do a 120s period of normal breathing, followed by ten breath-holds of 21s interleaved with normal breathing periods of 42s, following audio cues. ASL images were realigned and coregistered to anatomical T1 and sinc-interpolated to double the time resolution, followed by subtraction of label and control to generate perfusion weighted images13 and then converted to CBF maps using the single-compartment Buxton’s kinetic quantification model.14 The paradigm achievement was monitored by means of respiratory bellows from the MRI. A regressor adapted to breath-hold achievement was obtained and modeled as a ramp.6 Baseline CBF was calculated averaging the first 40 images of normal breathing. The CBF response to BH was delayed with respect to the respiratory trace.1,3,6,7,15–17 Six ramp regressors with delays from 6s to 21s were tested, and the one with the highest correlation with the GM CBF was used to estimate CVR.Mean CBF and CVR values were obtained from five different masks. Segmentation masks of GM and WM were generated from T1 image with manual removal of cerebellum and tumor. WM mask was eroded (disk size 5) to avoid partial volume effects. Three tumor related masks were manually obtained by a neuroradiologist from pre and post-contrast T1-weighted image, and FLAIR T2-weighted image: contrast enhanced tumor (CET), non-contrast-enhanced tumor (NCET) and edema. These masks were eroded (disk size 1) to avoid partial volume effects in tumor tissue quantifications. CBF and CVR values in the tumor masks were normalized by the GM, to compute CBF and CVR ratios. Edema values were normalized to WM, because edema is more related to WM. Differences in CBF and CVR ratios between grade III and IV groups were evaluated using non-parametric Wilcoxon-tests. Difference between GM and WM CVR for the whole group was computed with a paired Wilcoxon-test.Results

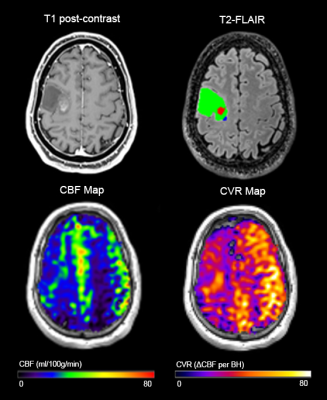

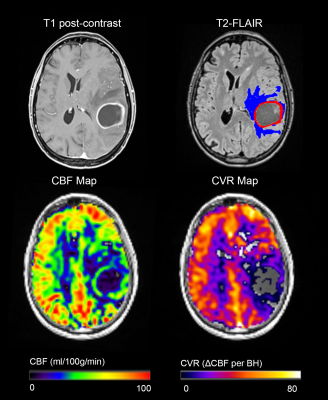

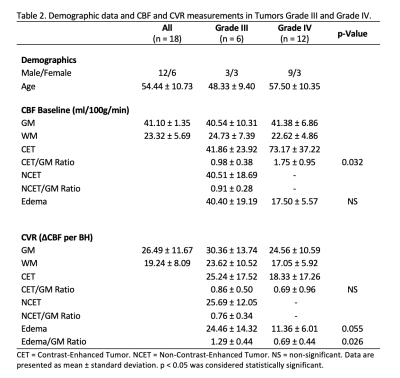

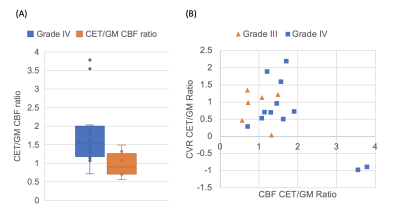

Successful ASL acquisitions were performed in all patients. A mean delay of 4±1 images (12±3s) was found across patients. Images from a representative patient with a grade III glioma are shown in Figure 2, and for grade IV glioma in Figure 3. CBF and CVR measurements are shown in Figure 4. Statistical tests showed significant differences in: CET CBF ratio between grade III and grade IV gliomas (p=0.032; Fig. 5a); CVR between GM and WM in the whole group (p<0.001); and edema CVR ratio between grade III and grade IV gliomas (p=0.026). CVR Edema/WM ratio (p=0.026) was significant. In general, CVR was reduced in gliomas with respect to the GM values. Values were lower in grade IV than grade III tumors, although the difference was not significant.Discussion

CBF ratio was higher in grade IV than grade III gliomas, as expected. CVR in tumor areas was decreased compared to GM CVR values. In contrast-enhanced areas, CVR ratio was lower in grade IV than grade III tumors (difference was not significant). This could indicate that the response to hypercapnia is further reduced in higher grade gliomas. Moreover, the data showed that the two grade IV tumors with the highest CBF had negative CVR (Fig. 5b). It has been reported that hypercapnia could cause a redistribution of blood from tumor regions to other tumor regions and surrounding normal tissue, causing a focal steal phenomenon leading to severely impaired CVR.18 Edema CVR ratio was found lower in grade IV than in grade III gliomas. It is known that diffuse gliomas may impact CVR on a widespread area.9Conclusion

PCASL combined with breath-holding enables measure of CBF and CVR in patients with cerebral tumors. More studies are needed to assess the CVR heterogeneity in tumoral tissue.Acknowledgements

Funding: Sergio M. Solís-Barquero received PhD grant support from Fundación Carolina and Universidad de Costa Rica. Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation (grant: PI18/00084).References

1. Kastrup, A., Krüger, G., Glover, G. H., Neumann-Haefelin, T. & Moseley, M. E. Regional Variability of Cerebral Blood Oxygenation Response to Hypercapnia. Neuroimage 10, 675–681 (1999).

2. Kastrup, A., Krüger, G., Neumann-Haefelin, T. & Moseley, M. E. Assessment of cerebrovascular reactivity with functional magnetic resonance imaging: comparison of CO 2 and breath holding. Magn Reson Imaging 19, 13–20 (2001).

3. Bright, M. G. & Murphy, K. Reliable quantification of BOLD fMRI cerebrovascular reactivity despite poor breath-hold performance. Neuroimage 83, 559–568 (2013).

4. Bright, M. G., Donahue, M. J., Duyn, J. H., Jezzard, P. & Bulte, D. P. The effect of basal vasodilation on hypercapnic and hypocapnic reactivity measured using magnetic resonance imaging. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism 31, 426–438 (2011).

5. Murphy, K., Harris, A. D. & Wise, R. G. Robustly measuring vascular reactivity differences with breath-hold: Normalising stimulus-evoked and resting state BOLD fMRI data. Neuroimage 54, 369–379 (2011).

6. Solis-Barquero, S. M. et al. Breath-Hold Induced Cerebrovascular Reactivity Measurements Using Optimized Pseudocontinuous Arterial Spin Labeling. Front Physiol 12, 1–11 (2021).

7. Pillai, J. J. & Mikulis, D. J. Cerebrovascular Reactivity Mapping: An Evolving Standard for Clinical Functional Imaging. American journal of neuroradiology 36, 7–13 (2015).

8. Holodny, A. I. et al. The Effect of Brain Tumors on BOLD Functional MR Imaging Activation in the Adjacent Motor Cortex : Implications for Image-guided Neurosurgery. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 21, 1415–1422 (2000).

9. Fierstra, J. et al. Diffuse gliomas exhibit whole brain impaired cerebrovascular reactivity. Magn Reson Imaging45, 78–83 (2018).

10. Attwell, D. et al. Glial and neuronal control of brain blood flow. Nature 468, 232–243 (2010).

11. Domenico, Z., Jovicich, J., Nadar, S., Voyvodic, J. T. & Pillai, J. J. Cerebrovascular reactivity mapping in patients with low grade gliomas undergoing presurgical sensorimotor mapping with BOLD fMRI. Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging 40, 383–390 (2014).

12. Louis, D. N. et al. The 2021 WHO classification of tumors of the central nervous system: A summary. Neuro Oncol 23, 1231–1251 (2021).

13. Aguirre, G. K., Detre, J. A., Zarahn, E. & Alsop, D. C. Experimental design and the relative sensitivity of BOLD and perfusion fMRI. Neuroimage 15, 488–500 (2002).

14. Buxton, R. B. et al. A general kinetic model for quantitative perfusion imaging with arterial spin labeling. Magn Reson Med 40, 383–396 (1998).

15. Birn, R. M., Smith, M. A., Jones, T. B. & Bandettini, P. A. The respiration response function: The temporal dynamics of fMRI signal fluctuations related to changes in respiration. Neuroimage 40, 644–654 (2008).

16. Magon, S. et al. Reproducibility of BOLD signal change induced by breath holding. Neuroimage 45, 702–712 (2009).

17. Blockley, N. P., Driver, I. D., Francis, S. T., Fisher, J. A. & Gowland, P. A. An improved method for acquiring cerebrovascular reactivity maps. Magn Reson Med 65, 1278–1286 (2011).

18. Hsu, Y. Y. et al. Blood Oxygenation Level-Dependent MRI of Cerebral Gliomas during Breath Holding. Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging 19, 160–167 (2004).

Figures