1739

Structural waste clearance markers in the elderly: sex differences in the relation between perivascular and parasagittal dural space volume1Department of Radiology & Nuclear Medicine, Maastricht University Medical Center, Maastricht, Netherlands, 2School for Mental Health and Neuroscience, Maastricht University, Maastricht, Netherlands, 3Department of Psychiatry & Neuropsychology, Maastricht University, Maastricht, Netherlands, 4Department of Neurology, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN, United States, 5Department of Biomedical Engineering, Eindhoven University of Technology, Eindhoven, Netherlands, 6Department of Radiology and Radiological sciences, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN, United States, 7Faculty of Psychology and Neuroscience, Maastricht University, Maastricht, Netherlands, 8School for Mental Health & Neuroscience, Maastricht University, Maastricht, Netherlands, 9Cardiovascular Research Institute Maastricht, Maastricht University, Maastricht, Netherlands, 10Department of Electrical Engineering, Eindhoven University of Technology, Eindhoven, Netherlands

Synopsis

Keywords: Neurodegeneration, Neurofluids, Sex differences, Perivascular spaces, Waste clearance

Cerebral waste clearance reduces with healthy aging and occurs in various neurodegenerative diseases. Both perivascular spaces (PVS) and the parasagittal dural (PSD) space play important roles in waste clearance, where the former transports waste products through the parenchyma, the latter is associated with cerebrospinal fluid efflux from the cranial compartment. The current 7T MRI study investigated sex differences in the relation between PVS and PSD volume in an elderly sample. By identifying a relationship between PVS and PSD solely in females, this study illustrates the possibility of a different impairment mechanism of the clearance system between elderly men and women.Introduction

Reduced cerebral waste clearance occurs both in healthy ageing and various neurodegenerative diseases1-5. For instance, in Alzheimer’s disease (AD), which is known to have a higher prevalence in females6.Among the different waste clearance pathways, recent studies have shown molecular passage out of the sub-arachnoid space to a region surrounding the superior sagittal sinus7, the parasagittal dural (PSD) space8. Recent work has proposed an automated method to segment PSD-volumes and suggested that increased PSD-volume could be indicative of higher waste accumulation, resulting in inflammation and subsequent PSD expansion9. PSD-volume is generally larger in males than females9, prompting potential sex differences in the relation between PSD and clearance impairment.

Perivascular spaces (PVS) are another important part of the clearance system10. PVS are the fluid-filled spaces surrounding cerebral blood vessels which transport fluid containing waste products in and out of the parenchyma11. Therefore, various studies have put forward MRI-visible PVS as a marker of altered clearance11-14.

As PVS are thought to drain the waste products into the subarachnoid space with subsequent movement to the PSD, understanding the interplay between the two structures might provide important information about the alteration of different parts of the clearance system. Driven by sex differences in the risk of developing certain neurodegenerative diseases6,15,16, we explored whether dissimilarities in impairment of the cerebral clearance mechanism in aging males and females could be a potential contributing factor to sex-related disparities in this risk. Therefore, considering potential sex differences, this study specifically looked at the relation between PVS-volume and PSD-volume in an elderly population.

Methods

Subjects:Twenty cognitively healthy elderly (twelve females, eight males) were included in this study (Tab.1).MRI acquisition:All subjects underwent 7 Tesla MRI (Siemens Healthcare, Erlangen, Germany) using a 32-element channel phased-array head coil. Anatomical T1-weighted, T2-weighted, and T2-weighted FLAIR images were acquired (Tab.2).

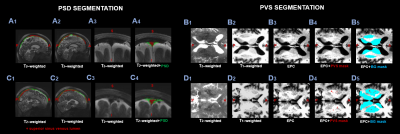

PSD-volumes:PSD-volumes were computed using a novel cascaded convolutional-neural networks method trained using T2-weighted images (see 9). To ensure accurate representation of the PSD variability between subjects, solely the parietal PSD-volume was utilized, which was not influenced by any frontal or posterior aliasing artefacts (Fig.1).

PVS-volumes:PVS-volumes were derived from two distinct locations which are known for PVS occurrence (i.e., the white matter (WM) and basal ganglia (BG))11. The WM and BG were automatically segmented using the T1-weighted images (Freesurfer, v5.1.0). Their respective volumes and total brain tissue volume (BTV; WM and gray matter) were calculated. Enhanced perivascular space contrast images were calculated for the PVS segmentation by dividing the coregistered T1-weighted image (FLIRT,FSL, v6.0.1)17 by the T2-weighted image18 (Fig.1)(Matlab 2019b; MathWorks). An in-house developed 3D U-Net was utilized to automatically segment the PVS in the WM, after which manual correction was performed. The PVS masks were manually drawn in the BG (Fig.1).

Relative PVS-volumes were derived by dividing the PVS-volume of the BG and WM by their respective total volumes.

Statistical analysis:Multivariable linear regression models were conducted for males and females separately, to investigate the relationship between relative BG and WM PVS-volumes and parietal PSD-volume. To check for potential confounding influences, age, and subsequently BTV, were added to the models as covariates.

Results

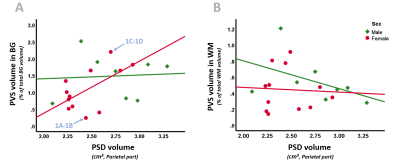

Table 1 summarizes the sample characteristics and descriptive statistics of the PVS and PSD measures.Only in females, a significant positive association was found between the relative BG PVS-volume and PSD-volume (β=.596, p=.041)(Tab.3), where a higher PVS-volume was related to a higher PSD-volume. This trend remained after correcting for age (β=.589, p=.063), but was no longer significant after additionally adjusting for BTV (β=.557, p=.106).

Discussion and conclusion

The current study found that a higher BG PVS-volume relates to a higher PSD-volume in females. Thereby, this study shows a relationship between two structural markers related to waste clearance and highlights the possibility to reduce clearance markers from anatomical images which are normally derived in clinical practice.Neurobiologically, the enlargement of PVS is suggested to be associated with polarization of AQP4 channels (linked to waste clearance), leakage and reduced PVS-flow11-14. This reduction in adequacy of waste clearance may result in a higher occurrence of waste products, leading to an accumulation of waste and subsequent inflammation at the level of the PSD, manifesting in PSD expansion - the drain of the clearance system9.

The current study only identified a relation between PSD-volume and PVS-volume in the BG, not the WM. Differences in segmentation method used per region could bias this regional difference, where the neural network used for WM PVS segmentation might be insufficient in its sensitivity and is still a work in progress.

By identifying a relation between PVS and PSD solely in females, this study illustrates the possibility of a different impairment mechanism of the clearance system between males and females. These sex differences could represent a potential contributing factor to the higher risk of females in developing certain neurodegenerative diseases, such as AD6, where reduced Amyloid-Beta clearance affects the development of AD1. However, the higher age of our male participants, could signify their PSD to be already quite enlarged9, resulting in a less evident relationship between PSD and PVS. We are currently expanding the sample size, allowing for a more detailed investigation of potential confounding effects on the association between PSD and PVS in relation to sex.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by Alzheimer Nederland (research grant WE.03-2018-02).References

1. Tarasoff-Conway JM. Clearance systems in the brain - implications for Alzheimer disease. Nature Reviews Neurology. 2015;11(8):457.

2. Rasmussen MK, Mestre H, Nedergaard M. The glymphatic pathway in neurological disorders. The Lancet Neurology. 2018;17(11):1016-1024.

3. Bakker EN, Bacskai BJ, Arbel-Ornath M, et al. Lymphatic clearance of the brain: perivascular, paravascular and significance for neurodegenerative diseases. Cellular and molecular neurobiology. 2016;36(2):181-194.

4. Reeves BC, Karimy JK, Kundishora AJ, et al. Glymphatic system impairment in Alzheimer’s disease and idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus. Trends in molecular medicine. 2020;26(3):285-295.

5. Joseph CR. Novel MRI Techniques Identifying Vascular Leak and Paravascular Flow Reduction in Early Alzheimer Disease. Biomedicines. 2020;8(7):228.

6. Laws KR, Irvine K, Gale TM. Sex differences in Alzheimer's disease. Current Opinion in Psychiatry. 2018;31(2).

7. Park M, Park JP, Kim SH, Cha YJ. Evaluation of dural channels in the human parasagittal dural space and dura mater. Annals of Anatomy - Anatomischer Anzeiger. 2022;244:151974.

8. Ringstad G, Eide PK. Cerebrospinal fluid tracer efflux to parasagittal dura in humans. Nature Communications. 2020;11(1):354.

9. Hett K, McKnight CD, Eisma JJ, et al. Parasagittal dural space and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) flow across the lifespan in healthy adults. Fluids and Barriers of the CNS. 2022;19(1):24.

10. Jessen NA, Munk ASF, Lundgaard I, Nedergaard M. The glymphatic system: a beginner’s guide. Neurochemical research. 2015;40(12):2583-2599.

11. Wardlaw JM, Benveniste H, Nedergaard M, et al. Perivascular spaces in the brain: anatomy, physiology and pathology. Nature Reviews Neurology. 2020:1-17.

12. Mestre H, Kostrikov S, Mehta RI, Nedergaard M. Perivascular spaces, glymphatic dysfunction, and small vessel disease. Clinical science. 2017;131(17):2257-2274.

13. Gouveia-Freitas K, Bastos-Leite AJ. Perivascular spaces and brain waste clearance systems: relevance for neurodegenerative and cerebrovascular pathology. Neuroradiology. 2021;63(10):1581-1597.

14. Barisano G, Lynch KM, Sibilia F, et al. Imaging perivascular space structure and function using brain MRI. NeuroImage. 2022:119329.

15. Weber CM, Clyne AM. Sex differences in the blood–brain barrier and neurodegenerative diseases. APL Bioengineering. 2021;5(1):011509.

16. Hanamsagar R, Bilbo SD. Sex differences in neurodevelopmental and neurodegenerative disorders: Focus on microglial function and neuroinflammation during development. The Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. 2016;160:127-133.

17. Jenkinson M, Bannister P, Brady M, Smith S. Improved optimization for the robust and accurate linear registration and motion correction of brain images. Neuroimage. 2002;17(2):825-841.

18. Sepehrband F, Barisano G, Sheikh-Bahaei N, et al. Image processing approaches to enhance perivascular space visibility and quantification using MRI. Scientific Reports. 2019;9(1):12351.

Figures

Table 1. Sample characteristics and descriptive statistics of the MRI measures for males and females individually. Mean (standard deviation) are reported unless stated otherwise.

Abbreviations: PSD = parasagittal dural sinus, PVS = perivascular space, BG = basal ganglia, WM = white matter, MMSE = Mini-Mental State Examination.

Table 2. This table summarizes the acquisition parameters of the sequences used within the study.

Abbreviations: TR = repetition time; TE = echo time; TI = inversion time; EPI = echo planar imaging.

Figure 1. Example images of a female subject (67y) with a low PSD (A) and BG PVS-volume (B) and a female subject (60y) with a high PSD (C) and BG PVS-volume (D).

The PSD segmentation (in green) is shown on the left, showing sagittal T2-w (A1-A2-C1-C2) and coronal images (A3-C3).

PVS segmentation is illustrated on the right, showing axial T2-w (B1-D1), T1-w (B2-D2) and EPC (B3-D3) images. The PVS mask is shown in red (B4-D4) and the BG mask in blue (B5-D5).

Abbreviations: EPC = enhanced perivascular space contrast; PVS = perivascular space, PSD = parasagittal dural space, BG = basal ganglia.

Table 3. Multivariate linear regression models showing the associations between the PSD volume and relative PVS volume in the BG and WM (Model 1). Subsequently, age (in months) was added to the model (Model 2), after which total brain volume (gray matter and white matter) was additionally added to the model (Model 3).

β shown are standardized. Significant associations are shown in bold. * p < 0.05, + p < 0.1

Abbreviations: PVS = perivascular space, PSD = parasagittal dural space, BG = basal ganglia, WM = white matter.

Figure 2. Scatterplots of PSD volume with BG (A) and WM (B) PVS volume, separated for sex (males = green, females = pink). A). In females, a higher BG PVS volume significantly relates to a higher PSD volume. B). No significant relationships are observerd between PSD and WM PVS volume.

Blue arrows point to the subjects used to present exemplary PSD and PVS volume maps in Figure 1, i.e., a subject with low BG PVS and PSD volume (1A-1B) and a subject with high BG PVS and PSD volume (1C-1D).

Abbreviations: PVS = perivascular space, PSD = parasagittal dural space, BG = basal ganglia, WM = white matter.