1738

Abnormal effective connectivity of reward network in first-episode schizophrenia with auditory verbal hallucinations1Department of Magnetic Resonance Imaging, The First Affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University, Zhengzhou, China, 2Laboratory for Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging and Molecular Imaging of Henan Province, Magnetic Resonance Imaging, Zhengzhou, China

Synopsis

Keywords: Neurodegeneration, fMRI (resting state), Auditory verbal hallucinations /effective connectivity/ reward network/ dopamine

Our study employs the dynamic causal modeling (DCM) approach to perform effective connectivity (EC) analysis of the reward network to investigate the mechanisms underlying schizophrenia patients with auditory verbal hallucinations (AVHs). This study enrolled 86 first-episode drug-naïve schizophrenia patients with AVHs (AVH), 93 patients without AVHs (NAVH), and 88 normal controls (NC), undergoing resting-state functional magnetic resonance. Our findings suggest that there are some common and different EC abnormalities in the reward network of AVH and NAVH. Particularly, the abnormalities of mesolimbic and mesocortex pathways in AVH may provide guidance for understanding the neurobiological mechanisms of AVHs and treatment.Introduction

Auditory verbal hallucinations (AVHs), defined as hearing and perceiving voices without external auditory stimulus input, are a prominent positive feature of schizophrenia. The "dopamine hypothesis" of schizophrenia associates dopamine with abnormal salience and proposes that irregular dopamine release causes the brain to assign "abnormal salience" to unrelated stimuli, which leads to positive symptoms, such as AVHs1, 2. And this series of processes may have linked the processing of abnormal salience with the information exchange of a network that includes the dopamine system (especially the ventral tegmental area (VTA) and ventral striatum (VS)) and its projection regions3, 4. For example, VTA controls dopamine synthesis and release5, VS is responsible for abnormal saliency processing and attribution6, 7, anterior insula/ anterior cingulate cortex (AI/ACC) controls abnormal saliency detection and functional transformation8, ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC) performs social cognition and reward value processing9, and posterior cingulate cortex (PCC) is also involved in learning and motivational functions in addition to being responsible for integrating memory and sensory information10, 11. At the same time, this bottom-up projection is also controlled and regulated by the PFC12, 13. Therefore, AVHs in schizophrenia may be associated with increased bottom-up dopamine projection and decreased top-down cognitive control of abnormal salience. However, the interactions between these brain regions and the abnormal flow of information remain unclear. Previously resting-state functional connectivity (rs-FC) can characterize information transfer between brain regions. However, the FC approach does not solve the directionality problem well. Recently, a hypothesis-driven analysis method based on a Bayesian model comparison procedure was known as dynamic causal modeling (DCM). DCM can identify causal links between brain areas or a given network and has become a popular method of measuring effective connectivity (EC) in resting-state functional magnetic resonance (rs-fMRI) data. This study aimed to investigate the mechanisms of abnormal EC of the reward network for schizophrenia patients with AVHs.Materials and Methods

This study recruited 181 drug-naïve first-episode schizophrenia (86 patients with AVHs (AVH), 93 patients without AVHs (NAVH)) and 88 age- and sex-matched normal controls (NC). All participants were scanned using 3.0 T MRI scanner with 8-channel receiver array head coil (Discovery MR750, GE, USA). The rs-fMRI images were collected using the following parameters in a gradient-echo single-shot echo-planar imaging sequence: repetition time / echo time = 2000/30ms, slice thickness = 4 mm, slice gap = 0.5 mm, flip angle = 90°, slice number = 32, field of view (FOV) = 22 × 22 cm2, number of averages = 1, matrix size = 64 × 64, voxel size = 3.4375 × 3.4375 ×3.4375 mm3. The spectral DCM analyses were performed by using DCM12, which is based on SPM12. First, we defined eight regions of interest based on earlier studies and our assumption. Second, extract the time series, create a general linear model with a nuisance regressor, and estimate the model parameters. Third, we obtained the mean connection strength across all subjects with a posterior probability > 0.95 (group mean for three groups' sample). Finally, the connectivity coefficients for each group were assessed with the one-sample Wilcoxon-Signed-Rank test and compared to a value of 0. Kruskal-Walli's H test and Dunn's test were used as post hoc tests to assess differences between groups. Spearman correlation analysis was performed to correlate between-group differential ECs with clinical scales. Receiver operating characteristics (ROC) were used to identify differential EC with potential clinical significance.Results

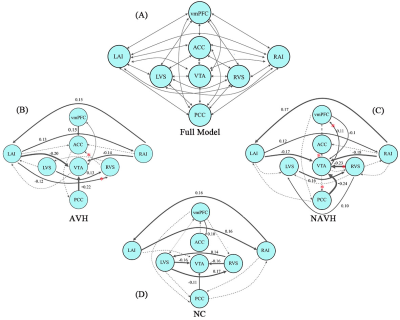

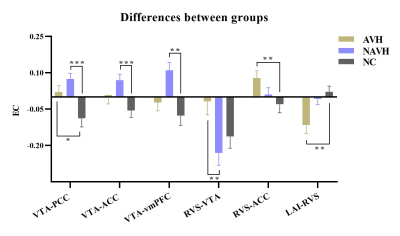

The full model and the one-sample Wilcoxon-Signed-Rank test are shown in (Figure 1). We can see that the AVH and NAVH exhibited complex connectivity pattern abnormalities compared to the NC. The VTA acts as a key node in and out, establishing extensive connections with other brain regions. Connections entering the VTA are usually inhibitory, while outgoing connections are usually excitatory. The intergroups comparisons (Kruskal-Walli’s H test) revealed that decreased negative EC from the RVS to VTA in AVH compared to NAVH. Compared to NC, AVH showed increased negative EC from left AI to RVS, increased positive EC from RVS to ACC, and increased positive EC from VTA to PCC, NAVH showed increased positive EC from VTA to PCC, ACC, and vmPFC (Figure 2). The results related to the clinical scales and ROC analysis are shown in Figure 3.Discussion and conclusion

These findings suggest that dopamine-related mesolimbic, and mesocortical abnormalities are associated with schizophrenia. In particular, the abnormal coupling between AI and ACC extends our understanding of the neurobiological mechanisms of reward networks in AVHs.Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their gratitude to the individuals who participated in this study. We also express our gratitude to the technical staff of the Magnetic Resonance Department of the First Affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University, who helped to acquire images of patients, and the staff of the Department of Psychiatry of the First Affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University. And, all authors declared no conflict of interest.References

1. Howes OD, Kapur S. The dopamine hypothesis of schizophrenia: version III--the final common pathway. Schizophr Bull May 2009;35(3):549-562.

2. Heinz A, Murray GK, Schlagenhauf F, Sterzer P, Grace AA, Waltz JA. Towards a Unifying Cognitive, Neurophysiological, and Computational Neuroscience Account of Schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull Sep 11 2019;45(5):1092-1100.

3. Strauss GP, Waltz JA, Gold JM. A review of reward processing and motivational impairment in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull Mar 2014;40 Suppl 2:S107-116.

4. Kesby JP, Murray GK, Knolle F. Neural Circuitry of Salience and Reward Processing in Psychosis. Biological Psychiatry Global Open Science 2021.

5. Morales M, Margolis EB. Ventral tegmental area: cellular heterogeneity, connectivity and behaviour. Nat Rev Neurosci Feb 2017;18(2):73-85.

6. Gradin VB, Waiter G, O'Connor A, Romaniuk L, Stickle C, Matthews K, Hall J, Douglas Steele J. Salience network-midbrain dysconnectivity and blunted reward signals in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res Feb 28 2013;211(2):104-111.

7. Haber SN. Integrative Networks Across Basal Ganglia Circuits. Handbook of Basal Ganglia Structure and Function, Second Edition; 2016:535-552.

8. Kowalski J, Aleksandrowicz A, Dabkowska M, Gaweda L. Neural Correlates of Aberrant Salience and Source Monitoring in Schizophrenia and At-Risk Mental States-A Systematic Review of fMRI Studies. J Clin Med Sep 13 2021;10(18).

9. Hiser J, Koenigs M. The Multifaceted Role of the Ventromedial Prefrontal Cortex in Emotion, Decision Making, Social Cognition, and Psychopathology. Biol Psychiatry Apr 15 2018;83(8):638-647.

10. Pearson JM, Heilbronner SR, Barack DL, Hayden BY, Platt ML. Posterior cingulate cortex: adapting behavior to a changing world. Trends Cogn Sci Apr 2011;15(4):143-151.

11. Liang S, Deng W, Li X, et al. Aberrant posterior cingulate connectivity classify first-episode schizophrenia from controls: A machine learning study. Schizophr Res Jun 2020;220:187-193.

12. Susan R. Sesacka, David B. Carrb. Selective prefrontal cortex inputs to dopamine cells: implications for schizophrenia. Physiology & Behavior 2002;77.

13. Rolls ET. Attractor cortical neurodynamics, schizophrenia, and depression. Transl Psychiatry Apr 12 2021;11(1):215.

Figures