1731

Assessment of Brainstem volume in Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic fatigue syndrome and long-COVID patients1Griffith University, Gold coast, Australia, 2The University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia

Synopsis

Keywords: Neurodegeneration, Brain

COVID -19 caused by the novel Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) has infected more than 600 million and caused the deaths of over six million people worldwide. The majority of the infected patients do not recover fully from the COVID-19 infections and develop post-COVID conditions also known as long-COVID has similar symptoms compared to Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic fatigue syndrome. In this study, we evaluated the volumetric changes in the brainstem regions in ME/CFS, long-COVID patients compared to healthy controls. Our study showed that brainstem volumes higher in ME/CFS and long-COVID patients compared to healthy controls.Introduction

Myalgic Encephalomyelitis (ME) also known as Chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS) (ME/CFS) is a complex illness characterised by profound fatigue for more than 6 months that impairs cognitive and motor dysfunction, and unrefreshing sleep1 that are similar to the symptoms in the long-COVID patients2. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is non-invasive, can detect subtle changes in brain structure and has been used to study brain dysfunction in ME/CFS and COVID patients. Recently, an ME/CFS study demonstrated increased hippocampal subfield volumes3 and reduced caudal middle frontal volume and precuneus thickness4. An MRI study in COVID-19 patients showed reduced grey matter thickness in the para-hippocampal gyrus, anterior cingulate cortex, and temporal lobe5. The brainstem region regulates respiratory, cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, and neurological processes which are the most common symptoms of ME/CFS and long-COVID patients. Therefore, the specific aims of this study was to quantify volumes of brainstem subregions and the whole brainstem in ME/CFS and long-COVID and compare them to healthy controls.Methods

The study was approved by the local human ethics (HREC/2019/QGC/56469) committee of the Gold Coast University Hospital and written informed consent was obtained from all individuals. MRI was performed on a 7 T whole-body MRI research scanner (Siemens Healthcare, Erlangen, Germany) with a 32-channel head coil (Nova Medical Wilmington, USA). We acquired T1-weighted data using a Magnetisation prepared 2 rapid acquisition gradient echo sequence (MP2RAGE) as in7. In brief, MP2RAGE data were acquired sagittally using the following parameters: repetition time (TR) = 4300 ms, echo time (TE) = 2.45 ms, first inversion time (TI1) = 840 ms, TI2 = 2370 ms, first flip angle (FA1) = 5o, FA2 = 6o and resolution = 0.75 mm3 with matrix size = 256 × 300 × 320. MP2RAGE data were processed similarly to our previous publications5 using FreeSurfer version 7.1.1 8 (https://surfer.nmr.mgh.harvard.edu/). Detailed information about the pipeline can be found at (https://surfer.nmr.mgh.harvard.edu/fswiki/recon-all) Brainstem subregions were segmented using the FreeSurfer 7.1.1 brainstem module8 as shown in Figure 1. Using this module, the brainstem was segmented into the midbrain, pons, superior cerebellar peduncle (SCP), and medulla oblongata. Brainstem subregions for all participants were visually checked for distortion-free segmentation. Multivariate general linear model (GLM) statistical analysis was performed to test brainstem subregions and whole brainstem volume differences between ME/CFS, long-COVID patients, and HC using SPSS version 28.Results

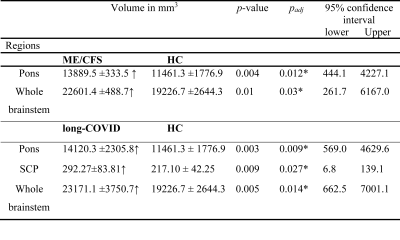

The brainstem subregion volumes were larger in ME/CFS patients compared to HC (see Table 1). After adjusting for multiple comparisons, volumes remained significantly larger in the pons (p<0.012) and whole brainstem region (p<0.03) (see Table 1). In long-COVID patients, after adjusting for multiple comparisons, we observed significantly larger volumes in the pons (p=0.009), SCP (p=0.027), and whole brainstem regions (p=0.014). Interestingly, no significant volumetric differences were obtained between ME/CFS and long-COVID patients.Discussion

Our study found significantly larger volumes for whole brainstem, pons, and SCP in ME/CFS and long-COVID patients. The brainstem contains the reticular activation system (RAS) . RAS neurons influence cortical function via two different pathways9. Brainstem nuclei constitute a circuit that controls both cortical arousal levels (cognition, wake / sleep, pain, respiration) and gait selection (eg walking or running)10. Therefore, structural changes in the brainstem of ME/CFS and long-COVID patients could result in severe and varied deficits in brain functionConclusion

In this pilot study, volumetric differences in brainstem regions were detected in ME/CFS and long-COVID relative to HC. Interestingly, we did not find any differences between ME/CFS and long-COVID in the whole brainstem and its subregion volumes.Acknowledgements

This research is funded by ME Research UK (MERUK, https://www.meresearch.org.uk/ ). Other funding bodies include: the Stafford Fox Medical Research Foundation (489798), the National Health and Medical Research Council (1199502), McCusker Charitable Foundation (49979), Ian and Talei Stewart, Buxton Foundation (4676), Henty Community (4879), Henty Lions Club (4880), Mason Foundation (47107), Mr Douglas Stutt, Blake Beckett Trust Foundation (4579), Alison Hunter Memorial Foundation (4570), and the Change for ME Charity (4575). We are also thankful to Ms. Tania Manning and Kay Schwarz for recruiting participants for this study, radiographers (Nicole Atcheson, Aiman Al-Najjar, Jillian Richardson, and Sarah Daniel) at the Centre for Advanced Imaging, The University of Queensland for helping us to acquire MRI data and all the patients and healthy controls who donated their time and effort to participate in this study. The authors acknowledge the facilities of the National Image Facility at the Centre for Advanced Imaging.References

1. Fukuda K. The Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: A Comprehensive Approach to Its Definition and Study. Ann Intern Med. 1994;121(12):953. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-121-12-199412150-00009

2. Komaroff AL, Bateman L. Will COVID-19 Lead to Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome? Frontiers in Medicine. 2021;7. Accessed September 29, 2022. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmed.2020.606824

3. Thapaliya K, Staines D, Marshall-Gradisnik S, Su J, Barnden L. Volumetric differences in hippocampal subfields and associations with clinical measures in myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome. J Neurosci Res. Published online March 31, 2022. doi:10.1002/jnr.25048

4. Thapaliya K, Marshall-Gradisnik S, Staines D, Su J, Barnden L. Alteration of Cortical Volume and Thickness in Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. Frontiers in Neuroscience. 2022;16. Accessed May 9, 2022. https://www.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fnins.2022.848730

5. Douaud G, Lee S, Alfaro-Almagro F, et al. SARS-CoV-2 is associated with changes in brain structure in UK Biobank. Nature. 2022;604(7907):697-707. doi:10.1038/s41586-022-04569-5

6. Thapaliya K, Urriola J, Barth M, Reutens DC, Bollmann S, Vegh V. 7T GRE-MRI signal compartments are sensitive to dysplastic tissue in focal epilepsy. Magnetic resonance imaging. 2019;61:1-8.

7. Fischl B. FreeSurfer. NeuroImage. 2012;62(2):774-781. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.01.021

8. Iglesias JE, Van Leemput K, Bhatt P, et al. Bayesian segmentation of brainstem structures in MRI. Neuroimage. 2015;113:184-195. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2015.02.065

9. Saper CB, Fuller PM. Wake-sleep circuitry: an overview. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2017;44:186-192. doi:10.1016/j.conb.2017.03.021

10. Benarroch EE. Brainstem integration of arousal, sleep, cardiovascular, and respiratory control. Neurology. 2018;91(21):958-966. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000006537

Figures