1724

White Matter Alterations Evident with DTI, DKI and Axonal Radius Measurements in Clinical Presentation of Chronic Symptomatic mTBI1GE Research, Niskayuna, NY, United States, 2Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, Bethesda, MD, United States, 3Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, Bethesda, MD, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Traumatic brain injury, Diffusion/other diffusion imaging techniques

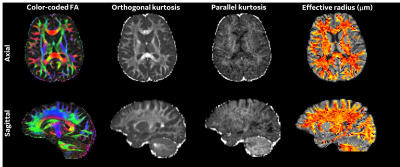

Diffusion MRI based microstructural evaluation of DTI, DKI, and intra-axonal radii, enabled by the ultra-high performance MAGNUS gradients, was leveraged in this study to assess differences between healthy controls and chronic mild traumatic brain injury presentations. Parcel-wise group and brain WM asymmetry analysis highlighted specific sub-region involvement differing from healthy controls in evaluated metrics. Subject specific analysis highlighted specific anatomical regions that could be more susceptible in TBI with the effect size potentially masked with central tendency analysis.Introduction

Impact acceleration forces are the leading cause for TBI resulting in a spectrum of damage from contusion to cortical/subcortical structures, diffuse injury as a result of shearing, axonal swelling and/or myelin disruption1–3. White-matter (WM) axons are particularly vulnerable to diffuse injury with insult to the axonal cytoskeleton impacting connectivity, with a number of mTBI studies reporting altered laterization and hemispheric differences4,5.WM pathology detected with neuroimaging is confounded by factors such as blood flow/edema and Wallerian degeneration, occurring under the umbrella of axonal insult1. Impacts are not evident in conventional MR/CT anatomical images, however dMRI holds promise as derived metrics serve as a proxy measure for assessing axonal integrity6. Established metrics derived from tensor(DTI) and kurtosis(DKI) are sensitive to the tissue micro-environment, but can be non-specific7. With the capabilities of high-performance gradient coils8,9 these metrics can be evaluated in a more relevant parameter space (shorter TE, higher b-values), while ultra-high diffusion(≥30 ms/μm2) encoding can be leveraged to simplify models of intra-axonal effective radii(reff)10.

In this study we present preliminary findings from an ongoing clinical research study using the MAGNUS gradient8. Here, DTI, DKI and reff distributions in healthy controls and subjects presenting with chronic mTBI were evaluated. The ultra-high b-encoding cancels contributions from the extra-axonal space providing more specific insight into underlying WM microstructure which can be related to alterations in neuronal function or reflect mechanism for plasticity (explaining persistent symptomatology) following brain insult.

Methods

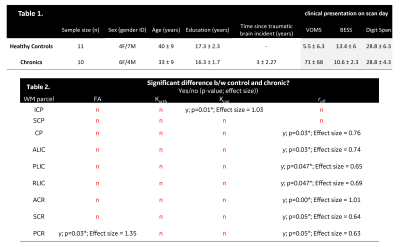

Acquisition: Ten healthy-controls and nine chronic (>3 months of persistent symptoms) mTBI subjects were scanned, under IRB-approved protocols at WRNMMC, using a 3.0 T MRI (GE Healthcare, Waukesha, WI, USA) fitted with a MAGNUS gradient coil (GE Research, Niskayuna, NY, USA). Subject recruitment demographic and clinical presentation is summarized in Table1. Postural stability and vestibulocular-related impairments were assessed using Balance Error Scoring System, and Vestibular/Ocular Motor Screening respectively. Two diffusion-weighted scans were acquired. DTI/DKI data was acquired with 125-directions (5 interspersed b=0s, b=0.5(ndir=30),2(ndir=40) and 4 ms/μm2(ndir=50)). Other parameters were: EPI echo-spacing 538 ms,TE/TR=44.6/5000 ms,1.5-mm isotropic resolution, over a total scan-time was 13 mins. For reff distributions radient directions were uniformly sampled11,12 for b=7,18,25, and 30 ms/μm2(ndir=60). Acquisition parameters were: EPI echo-spacing=448 ms, Δ/δ=33/19 ms, TE/TR=63/5500 ms, 2.2-mm isotropic resolution, over a total scan-time of ≤20 mins.All Diffusion weighted images were corrected for eddy current distortion, bulk motion, and gradient non-linearity for diffusion encoding13 implemented using a custom pipeline21,22. For DTI/DKI: Data was denoised with generalized spherical deconvolution14,15. DTI/DKI were fit using a non-negativity constrained least-squares approach. For reff: Decorrelated-phase filtering16 was used to output real-valued data to circumvent the limitations of Rician noise bias. Powder-averaged signal attenuation was modeled as previously defined10 to generate a projection of the tail-weighted reff distributions in the in-vivo brain.

Statistical analysis: Preliminary analysis was limited to WM parcels, using the JHU ICBM-DTI-8117. Group differences were evaluated by non-parametric statistical methods, permutation testing (iterations:30000), hedges-g to measure the corrected effect size. Test statistic thresholds were defined at p<0.05, with pFDR for multiple-comparisons. This was done over the following conditions: 1) Establishing asymmetric patterns in the healthy control participants, 2) Whole brain parcel-wise comparison between healthy controls and chronic TBI participants and 3) Group-wise and subject specific brain asymmetries.

Results & Discussion

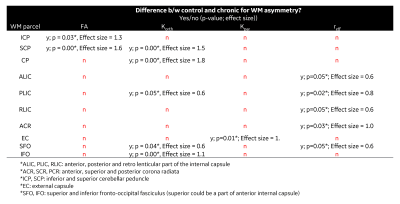

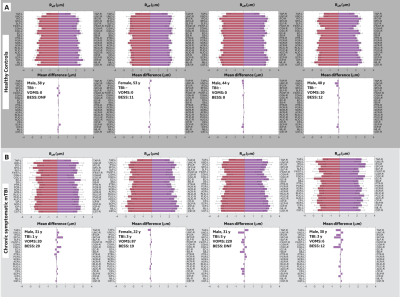

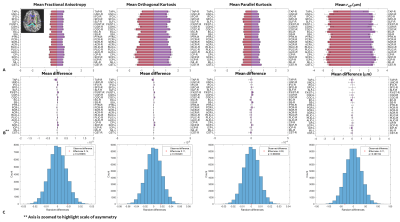

For control subjects, no significant differences are reported for brain lateralization/asymmetry evaluation over symmetric WM parcels for DTI, DKI and reff (Figure 2). Parcel-wise analysis between healthy-controls and chronic mTBI subjects highlighted anatomical regions that appear to be more susceptible to TBI (Table 2). With FA and parallel kurtosis, a large effect-size was noted in the posterior corona radiata and inferior cerebellar peduncles(Table 2). reff highlighted significant alterations in the internal capsule, corona radiata and cerebral peduncles (Table 2). These structures have previously been identified in meta-analysis studies4,18–20, as susceptible in acute-TBI populations.Parcel-wise asymmetry highlighted more involvement of anatomically specific regions (Table 3). Lateralization in DTI metrics was previously reported in the TRACK-TBI study, with similar anatomical distributions5. In the present study, corresponding differences in DKI and reff were also noted.

Differences in parcel-wise effect size are impacted by the heterogeneity in clinical representation of chronic TBI, stemming from time and type of injury, demographics, and pre/post co-morbidities, as well as volume averaging over the larger parcels. Indeed, when chronic subjects were analyzed for brain asymmetries on a subject specific basis, diverse WM burden in terms of asymmetries were noted with reff metrics (Figure 3). Future work will include smaller parcels similar to those used in the GE/NFL Head Health Initiative21. Further analysis will include a larger sample size for more accurate modeling of the control distribution while extending to voxel-based or tract-based spatial statistics.

Conclusion

In this study, preliminary results from an ongoing study for chronic TBI subjects are presented where DTI, DKI, and reff were evaluated. Uniquely, albeit with a smaller sample size, the study highlighted a broader involvement of group level parcel-wise differences in reff measures, while highlighting discrete patterns of asymmetries in specific brain regions in individual subjects. These findings indicate that the pathophysiology of injury has interesting neuroplastic components between control and chronic subjects and highlights the utility of reff as a specific clinical biomarker for mTBI.Acknowledgements

Grant funding from NIH U01EB028976, NIH U01EB024450, CDMRP W81XWH-16-2-0054.

The opinions or assertions contained herein are the views of the authors and are not to be construed as the views of the U.S. Department of Defense, Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, or the Uniformed Services University.

References

1. Palacios, E. M. et al. The evolution of white matter microstructural changes after mild traumatic brain injury: A longitudinal DTI and NODDI study. Science Advances 6, eaaz6892.

2. Arfanakis, K. et al. Diffusion Tensor MR Imaging in Diffuse Axonal Injury. AJNR: American Journal of Neuroradiology 23, 794 (2002).

3. Armstrong, R. C., Mierzwa, A. J., Marion, C. M. & Sullivan, G. M. White matter involvement after TBI: Clues to axon and myelin repair capacity. Exp Neurol 275 Pt 3, 328–333 (2016).

4. Eierud, C. et al. Neuroimaging after mild traumatic brain injury: Review and meta-analysis. NeuroImage: Clinical 4, 283–294 (2014).

5. Palacios, E. M. et al. Diffusion Tensor Imaging Reveals Elevated Diffusivity of White Matter Microstructure that Is Independently Associated with Long-Term Outcome after Mild Traumatic Brain Injury: A TRACK-TBI Study. Journal of Neurotrauma 39, 1318–1328 (2022).

6. Yuh, E. L. et al. Diffusion tensor imaging for outcome prediction in mild traumatic brain injury: a TRACK-TBI study. J Neurotrauma 31, 1457–1477 (2014).

7. Figley, C. R. et al. Potential Pitfalls of Using Fractional Anisotropy, Axial Diffusivity, and Radial Diffusivity as Biomarkers of Cerebral White Matter Microstructure. Frontiers in Neuroscience 15, (2022).

8. Foo, T. K. F. et al. Highly efficient head-only magnetic field insert gradient coil for achieving simultaneous high gradient amplitude and slew rate at 3.0T (MAGNUS) for brain microstructure imaging. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine 83, 2356–2369 (2020).

9. Huang, S. Y. et al. Connectome 2.0: Developing the next-generation ultra-high gradient strength human MRI scanner for bridging studies of the micro-, meso- and macro-connectome. Neuroimage 243, 118530 (2021).

10. Veraart, J. et al. Noninvasive quantification of axon radii using diffusion MRI. eLife 9, e49855 (2020).

11. Dk, J., Ma, H. & A, S. Optimal strategies for measuring diffusion in anisotropic systems by magnetic resonance imaging. Magnetic resonance in medicine vol. 42 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10467296/ (1999).

12. Jones, D. K. The effect of gradient sampling schemes on measures derived from diffusion tensor MRI: a Monte Carlo study. Magn Reson Med 51, 807–815 (2004).

13. Tan, E. T., Marinelli, L., Slavens, Z. W., King, K. F. & Hardy, C. J. Improved correction for gradient nonlinearity effects in diffusion-weighted imaging. J Magn Reson Imaging 38, 448–453 (2013).

14. Sperl, J. I. et al. Model-based denoising in diffusion-weighted imaging using generalized spherical deconvolution. Magn Reson Med 78, 2428–2438 (2017).

15. Abad, Nastaren, Marinelli, Luca, Madhavan, Radhika & Foo, TKF. Model Based Denoising of Diffusion MRI Reduces Bias in Tensor Derived Parameters and Connectivity Measures. in Proceedings for the International Society for Magetic Resonance in Medicine (2021).

16. Sprenger, T., Sperl, J. I., Fernandez, B., Haase, A. & Menzel, M. I. Real valued diffusion-weighted imaging using decorrelated phase filtering. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine 77, 559–570 (2017).

17. Oishi, K. et al. Human brain white matter atlas: Identification and assignment of common anatomical structures in superficial white matter. NeuroImage 43, 447–457 (2008).

18. Hutchinson, E. B., Schwerin, S. C., Avram, A. V., Juliano, S. L. & Pierpaoli, C. Diffusion MRI and the detection of alterations following traumatic brain injury. J Neurosci Res 96, 612–625 (2018).

19. Hoffer, M. E., Szczupak, M. & Balaban, C. Clinical trials in mild traumatic brain injury. J Neurosci Methods 272, 77–81 (2016).

20. Niogi, S. N. & Mukherjee, P. Diffusion Tensor Imaging of Mild Traumatic Brain Injury. The Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation 25, 241–255 (2010).

21. Li, X. et al. Single-subject Voxel-based Analysis for mTBI using Multi-shell Diffusion MRI. 4.

Figures

Table 1. Demographics, clinical and cognitive characteristics, and WM task performance of the enrolled individuals.

Table 2. Parcel wise analysis between healthy controls and chronic presentations for TBI are presented for DTI, DKI and intra-axonal radius measurements. The effect size was estimated using hedges-g using the conventional interpretation: ≤ 0.3, small effect size; ≤ 0.6, medium effect size, > 0.6, large effect size. Abbreviations: FA, Fractional Anisotropy; Korth, Orthogonal Kurtosis; Kpar, parallel Kurtosis; reff, effective axonal radius.