1723

Vascular reactivity of the choroid plexus in non-atherosclerotic vasculopathy: choroid plexus activity as a possible marker of ischemic stress

Caleb J. Han1, Spencer Waddle1, Maria Garza1, L. Taylor Davis2, Jarrod Eisma1, Rohan Chitale3, Matthew Fusco3, Colin D. McKnight2, Sky Jones1, Lori C. Jordan1,4, and Manus J. Donahue1,2,5

1Neurology, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN, United States, 2Radiology, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN, United States, 3Neurosurgery, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN, United States, 4Pediatrics, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN, United States, 5Psychiatry, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN, United States

1Neurology, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN, United States, 2Radiology, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN, United States, 3Neurosurgery, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN, United States, 4Pediatrics, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN, United States, 5Psychiatry, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Neurofluids, Stroke, Moyamoya, glymphatic, choroid plexus, cerebrovascular reactivity, CSF

This work applies hypercapnic reactivity and deep-learning techniques to evaluate choroid plexus (ChP) vascular compliance dependence on large arterial patency in intracranial vasculopathy. ChP reactivity was found to be preserved regardless of macrovascular vasculopathy, despite dependencies of resting ChP perfusion on cortical ischemia. Findings support the possibility that changes in resting ChP function in other studies in the presence of arterial vasculopathy and cerebral ischemia may be a response to circulating biochemical markers of ischemic stress, prompting the ChP to attenuate CSF production levels through feedback, rather than vascular mechanisms, to support glial health in ischemia.Introduction

The overall goal of this work is to apply hypercapnic reactivity and deep-learning techniques to evaluate choroid plexus (ChP) vascular compliance dependencies on arterial patency in patients with intracranial vasculopathy. It has recently been shown that the ChP, the primary site of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) production, can exhibit local hyperemia in patients with cerebral ischemia secondary to bilateral intracranial vasculopathy, which can reduce following successful surgical revascularization1. This suggests, but does not confirm, that ChP perfusion may provide a central marker of ischemic stress. One explanation underlying this observation is that compliance of microvasculature may be reduced during ischemia, prompting the ChP to increase CSF production to clear solutes along less compliant perivascular pathways. However, the ChP activity may also simply depend on changes in macrovascular arterial patency and the reserve capacity of the ChP itself. We investigate ChP and cortical vascular compliance by evaluating cerebrovascular reserve capacity in patients with intracranial vasculopathy with and without prior surgical revascularization. We hypothesize that, unlike in cortical blood flow territories, ChP vascular reserve is unaffected by intracranial stenosis; thus, changes in ChP activity following revascularization are likely to arise from circulating markers of ischemic stress.Materials and Methods

Demographics. Participants (n=58) were recruited from the neurosurgical services at our institute and had a clinical diagnosis of moyamoya (i.e., non-atherosclerotic) vasculopathy based on catheter angiography and neurological assessment. Prior surgical revascularization was not an exclusion criterion and was considered in the analysis.Experiment. All participants underwent clinically-indicated catheter angiography (bilateral internal carotid artery and vertebral artery injections)2 in sequence with non-contrasted anatomical MRI (T1-weighted, T2-weighted, T2-weighted FLAIR, and DWI), blood oxygenation level-dependent (BOLD; TE=35 ms; spatial resolution=3.5x3.5x3.5 mm, TR=2000 ms) at 3.0 Tesla (Philips)3. A paradigm of two blocks of 180s hypercapnia gas (5% CO2) interleaved with 180s normocapnia gas (~21% O2/~79% N2) was performed.

Analysis. A board-certified neuroradiologist graded stenotic or occluded vessels in each hemisphere from catheter angiography according to NASCET criteria4. Arterial stenosis was ranked ordinally: 0: no-to-69% stenosis present, 1: 70%-99% stenosis, 2: occlusion. Time regression analysis was performed for quantification of timing-uncorrected cerebrovascular reactivity (CVRRAW), maximum cerebrovascular reactivity (CVRMAX), and reactivity delay time (CVRDELAY)5. ChP structures in the atria of the lateral ventricles and third ventricles were localized by a convolution neural network algorithm applied to the T1-weighted scan6, 7. Cortical masks derived for the middle-cerebral-artery (MCA) flow territory map were used to determine CVR parameters in the proximity of the revascularization site, separately for the left and right hemispheres.

Statistics. This analysis aimed to understand whether published post-surgical ChP perfusion reductions1 were attributable to changes in the ChP parenchymal vascular reactivity. Each participant was categorized based on prior revascularization status, then further organized based on the vasculopathy ranking of their worst vessel. A one-way ANOVA test was applied, separately in ChP and MCA territories, for the reactivity parameters. Significance criterion: Bonferroni-corrected two-sided p<0.05.

Results

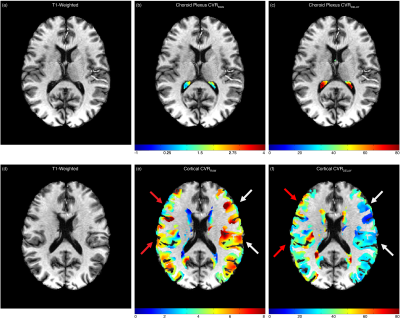

Table 1 summarizes participant demographics, including the cohort with (n=32; age=43.1±14.9 years) and without (n=26; age=49.8±14.0 years) prior revascularization surgeries. All surgeries were indirect (e.g., encephalo-duro-arterio-synangiosis, EDAS). Similar to a previously mentioned perfusion study1, all participants had stenosis or occlusion of at least one intracranial internal-carotid-artery or first segment of MCA but lacked posterior circulation stenosis. Fig. 1 shows examples of a representative participant's MCA and ChP regions. In patients without prior revascularization surgeries, the degree of arterial vasculopathy reduced CVRRAW and CVRMAX, and lengthened CVRDELAY in the MCA territories, as expected (p≤0.029) (Fig. 2). No significant change was observed in the MCA territory of post-surgical participants (Fig. 2), highlighting that, as expected, MCA territory reserve capacity is affected by arterial vasculopathy and improves following surgical revascularization. However, regardless of surgical history, the ChP reactivity statistics were not significantly related to the degree of stenosis (Fig. 3). Fig. 4 shows a representative example of ChP vs. cortical hemodynamics, demonstrating lateralizing effects in cortical regions and symmetric vascular compliance in ChP in a manner that is independent of arterial patency.Discussion

While cortical hemodynamics relate to proximal arterial patency and prior surgical history in non-atherosclerotic moyamoya vasculopathy, ChP reactivity was observed to be preserved regardless of large vessel vasculopathy and revascularization status. This supports the interpretation that previously reported changes in ChP hemodynamics1 following surgical revascularization are less likely related to the vascular supply of the ChP itself and more likely attributable to the ChP response to circulating markers of ischemic or glial stress. This is also consistent with the arterial supply of the ChP: anterior and posterior choroidal arteries, which branch from the posterior circulation, and are known to be less affected than anterior circulation vessels in moyamoya. Improved arterial supply to damaged or at-risk glial tissue could reduce biochemical signs of cellular stress secretion, prompting ChP to attenuate high CSF production levels which were previously necessary to clear neurofluid along less compliant perivascular pathways in times of vascular stress.Conclusion

Findings support that ChP reactivity is frequently preserved in moyamoya vasculopathy; as such, changes in ChP function in response to revascularization or circulating markers of cerebral ischemia are more likely to reflect central feedback phenomena rather than ChP vascular reserve changes.Acknowledgements

References

- Johnson SE, McKnight CD, Lants SK, Juttukonda MR, Fusco M, Chitale R et al. Choroid plexus perfusion and intracranial cerebrospinal fluid changes after angiogenesis. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2020; 40(8): 1658-1671.

- Donahue MJ, Ayad M, Moore R, van Osch M, Singer R, Clemmons P et al. Relationships between hypercarbic reactivity, cerebral blood flow, and arterial circulation times in patients with moyamoya disease. J Magn Reson Imaging 2013; 38(5): 1129-39.

- Donahue MJ, Dethrage LM, Faraco CC, Jordan LC, Clemmons P, Singer R et al. Routine clinical evaluation of cerebrovascular reserve capacity using carbogen in patients with intracranial stenosis. Stroke 2014; 45(8): 2335-41.

- Ferguson GG, Eliasziw M, Barr HW, Clagett GP, Barnes RW, Wallace MC et al. The North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trial : surgical results in 1415 patients. Stroke 1999; 30(9): 1751-8.

- Donahue MJ, Strother MK, Lindsey KP, Hocke LM, Tong Y, Frederick BD. Time delay processing of hypercapnic fMRI allows quantitative parameterization of cerebrovascular reactivity and blood flow delays. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2016; 36(10): 1767-1779.

- Eisma JJ, McKnight CD, Hett K, Elenberger J, Song AK, Stark AJ et al. Choroid plexus perfusion and bulk cerebrospinal fluid flow across the adult lifespan. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2022: 271678X221129101.

- Zhao L, Feng X, Meyer CH, Alsop DC. Choroid Plexus Segmentation Using Optimized 3D U-Net. In. 2020 IEEE 17th International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging (ISBI), 2020. pp 381-384.

Figures

Table 1. Demographic information for both surgical and nonsurgical cohorts.

Figure 1. (a) Axial slices depict the choroid plexus map on a participant (age = 40 years; sex = female). (b and c) A magnified view at the atria of the level of the lateral ventricles. (d) The white arrows indicate the approximate location of the indirect revascularization. Therefore, the cortical flow territory mask was created to co-localize with the parenchyma near the revascularization site. (e) The axial slices of the corresponding cortical mask.

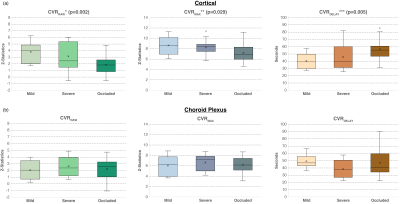

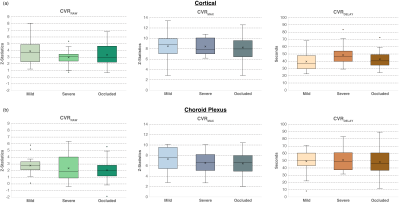

Figure 2. Boxplots visually contrast reactivity findings in the (a) cortex and (b) choroid plexus for participants who have not received any revascularization procedures. A one-way ANOVA test reveals that the reactivity statistics significantly differed between the different stenosis groups (*p = 0.002, **p = 0.029, and ***p = 0.005) in the cortex. However, no significance was found in the choroid plexus.

Figure 3. Boxplots contrast reactivity data in the (a) cortex near the revascularization site and (b) choroid plexus in participants who have received a revascularization procedure. In both territories, the reactivity does not significantly change as the stenosis differs, consistent with the therapeutic effect of the revascularization in the cortex.

Figure 4. A case example of a non-surgical 39-year-old Black female with moyamoya. This participant has an occluded right middle-cerebral-artery (score=2) and a mildly-stenosed left middle cerebral artery (score=0). (b-c) The choroid plexus CVRRAW and CVRDELAY are not significantly different. However, (e-f) the reactivity data in the cortical flow territory show evidence of reduced reactivity and lengthened reactivity delays in the right hemisphere in the territory supplied by the stenosis.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.58530/2023/1723