1722

Nigral volume as a marker for Lewy body pathology in Alzheimer’s disease1Center for Advanced Neuroimaging, University of California Riverside, Riverside, CA, United States, 2Department of Bioengineering, University of California Riverside, Riverside, CA, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Alzheimer's Disease, Dementia, lewy body

Up to 60% of Alzheimer's disease cases have Lewy body pathology. In Alzheimer's disease, Lewy body pathology is associated with more rapid cognitive decline, parkinsonism, and younger symptom onset. In this abstract, we examine nigral volume in Alzheimer's disease patients and patients with mild cognitive impairment with Lewy body pathology. We find that cognitively impaired patients with Lewy bodies have greater neuronal loss in substantia nigra pars compacta as well as reduced nigral volume.Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most frequent neurodegenerative dementia and it is estimated that 1 in 85 people will develop AD by 2050.1 Patients with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) experience a decline in cognition that do not meet the threshold for dementia but these patients are likely to convert to AD.2 AD and MCI pathology include the accumulation of b-amyloid into extracellular plaques and hyper-phosphorylated tau into intracellular neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs).3,4 Autopsy studies have found that up to 60% of AD cases have Lewy body (LB) pathology.5-7 In AD, LB copathology is associated with more rapid cognitive decline,8 parkinsonism,9 younger symptom onset,10 and shorter survival times.AD and MCI (AD/MCI) patients with LB (AD/MCI LB+) pathology have greater deficits in visuospatial and executive function as compared to AD/MCI without LB pathology (AD/MCI LB-).11 Further, analysis of FDG-PET images found reduced metabolism in the striatum12 and substantia nigra of AD/MCI LB+ patients.13 An MRI-based imaging marker to corroborate the presence of LB pathology and screen AD/MCI for LB pathology could improve clinical study designs and improve the odds of success of AD clinical trials. Here, we use neuromelanin-sensitive imaging to examine nigral volume in AD/MCI patients with and without LB pathology. Melanized neurons in substantia nigra pars compacta (SNc) can be imaged in vivo using implicit or explicit magnetization transfer (MT) effects14,15 and magnetization transfer contrast (MTC) colocalizes with melanized neurons.16

Methods

The Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) database (adni.loni.usc.edu) was queried for individuals diagnosed with AD or MCI with Institutional IRB approved the study for each site and subjects gave written informed consent. Criteria for inclusion of subjects from the ADNI database were as follows: participants must 1) have a diagnosis of AD or MCI, 2) have a neuropathologic evaluation in the ADNI database, and 3) be scanned with a multiecho TSE acquisition from the ADNI1 protocol. A total of 48 subjects (23 AD/MCI LB- participants and 25 AD/MCI LB+ participants) met these criteria. Imaging data were downloaded in March 2022.Neuropathologic evaluation in ADNI follows the National Institute on Aging and Alzheimer’s Association guidelines and of that of the Dementia with Lewy Bodies Consortium classification. Details of the neuropathologic protocol can be found in the ADNI database (http://adni.loni.usc.edu). Presence of LB was evaluated based on the degree and distribution of LB pathology: none, brainstem-predominant, limbic (transitional), neocortical (diffuse), amygdala-predominant, or olfactory-only. Neuronal loss in SNc was characterized in 4 stages: 0 – no loss, 1 – slight loss, 2 – moderate loss, 3 – extensive.

T1-weighted structural images in the ADNI cohort were used for registration to common space. Dual-echo TSE images were acquired with the following parameters: TE1/TE2/TR=11/101/3270 ms, FOV=240×213 mm2, voxel size=0.9×0.9×3 mm3, fat saturation pulse, 48 slices. The first echo of the TSE acquisition contains magnetization transfer effects from the fat saturation pulse and interleaved TSE acquisition.

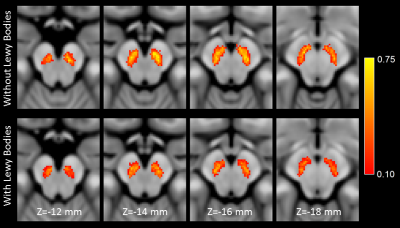

SNc was segmented using a thresholding method. A reference region was drawn in the cerebral peduncle in MNI common space and then transformed to individual TSE images and used to threshold. Voxels with intensity >mref+3sref were considered to be part SNc. Thresholding was restricted to the anatomic location of SNc using previously reported probabilistic standard space mask.

Results

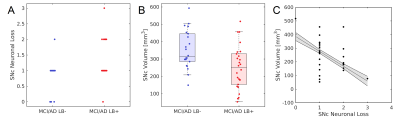

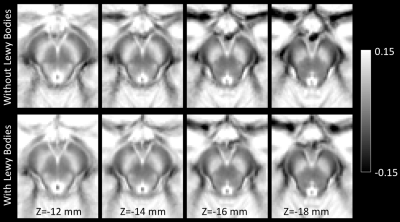

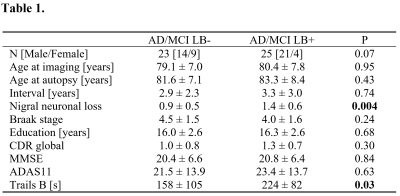

Demographic information for the groups used in this analysis is summarized in Table 1. A significant difference was seen in Trails-B (F=4.072;P=0.034). No differences in sex (P=0.070), age (F=0.004;P=0.948), MMSE (F=0.040;P=0.842), education (F=0.175;P=0.677), CDR score (F=1.121;P=0.295), or ADAS11 (F=0.229;P=0.634) score were observed between AD/MCI LB+ and AD/MCI LB- groups.Neuropathologic analysis of SNc found greater nigral neuronal loss in the AD/MCI LB+ group relative to the AD/MCI LB- group (F=9.041;P=0.004). Interestingly, comparison of nigral volume found reduced nigral volume in the AD/MCI LB+ group as compared to the AD/MCI LB- group (LB-: 348 mm3 ± 112 mm3; LB+ 245 mm3 ± 127 mm3; F=4.984, P=0.031). This comparison is shown in Figure 1 and a visual comparison of neuromelanin-sensitive contrast in SNc between groups is shown in Figure 2. A significant correlation was observed in the AD/MCI LB+ group between assessment of nigral neuronal loss and SNc volume (r=-0.448;P=0.016), controlling for age and sex, with lower volume correlated with greater nigral neuronal loss. No correlation was observed between SNc volume and any clinical measure (Ps>0.228).

Discussion

As compared to the AD/MCI LB- group, a reduction in nigral volume was seen in the AD/MCI LB+ group (Figures 1 and 2). This result agrees with earlier studies which found reduced metabolism in the basal ganglia of AD patients with LB pathology and suggests that imaging markers derived from the nigrostriatal system may identify individuals with LB pathology in AD/MCI. Finally, a negative association was found between nigral neuronal loss with nigral volume with lower volume being correlated with more extensive neuronal loss. This result may indicate that magnetization transfer effects (i.e. neuromelanin-sensitive contrast) are related to melanized neurons in SNc.Acknowledgements

Data collection and sharing for this project was funded by the Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) (National Institutes of Health Grant U01 AG024904) and DOD ADNI (Department of Defense award number W81XWH-12-2-0012). ADNI is funded by the National Institute on Aging, the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering, and through generous contributions from the following: AbbVie, Alzheimer’s Association; Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundation; Araclon Biotech; BioClinica, Inc.; Biogen; Bristol-Myers Squibb Company; CereSpir, Inc.; Cogstate; Eisai Inc.; Elan Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Eli Lilly and Company; EuroImmun; F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd and its affiliated company Genentech, Inc.; Fujirebio; GE Healthcare; IXICO Ltd.; Janssen Alzheimer Immunotherapy Research & Development, LLC.; Johnson & Johnson Pharmaceutical Research & Development LLC.; Lumosity; Lundbeck; Merck & Co., Inc.; Meso Scale Diagnostics, LLC.; NeuroRx Research; Neurotrack Technologies; Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation; Pfizer Inc.; Piramal Imaging; Servier; Takeda Pharmaceutical Company; and Transition Therapeutics. The Canadian Institutes of Health Research is providing funds to support ADNI clinical sites in Canada. Private sector contributions are facilitated by the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health (www.fnih.org). The grantee organization is the Northern California Institute for Research and Education, and the study is coordinated by the Alzheimer’s Therapeutic Research Institute at the University of Southern California. ADNI data are disseminated by the Laboratory for Neuro Imaging at the University of Southern California.References

[1] Brookmeyer, et al. Forecasting the global burden of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement 3:186-191.

[2] Albert, et al. The diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer's disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer's Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement 7:270–279.

[3] Morris, et al. APOE predicts amyloid-beta but not tau Alzheimer pathology in cognitively normal aging. Ann Neurol 67:122-131.

[4] Schmechel, et al. Increase amyloid beta-peptide deposition in cerebral cortex as a consequence of apolipoprotein E genotype in late-onset Alzheimer disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 90:9649-0653.

[5] Rocca, et al. Trends in the incidence and prevalence of Alzheimer’s disease, dementia, and cognitive impairment in the United States. Alzheimers Dement 7:80-93.

[6] Lippa, et al.Lewy bodies contain altered alpha-synuclein in brains of many familial Alzheimer’s disease patients with mutations in presenilin and amyloid precursor protein genes. Am J Pathol 153:1365-1370.

[7] Hamilton, RL. Lewy bodies in Alzheimer’s disease: a neuropathological review of 145 cases using alpha-synuclein immunohistochemistry. Brain Pathol 10:378-384.

[8] Azer, et al. Cognitive tests aid in clinicall differentiation of Alzheimer’s disease vs Alzheimers disease with Lewy body disease: evidence from a pathological study. Alzheimers Dement 16:1173-1181.

[9] Forstl, et al. The Lewy-body variant of Alzheimers disease. Clinical and pathological findings. Br J Psychiatry 16:1173-1181.

[10] Chung, et al. Clinical features of Alzheimer disease with and without Lewy bodies. JAMA Neurol 72:789-796.

[11] Savica, et al. Lewy body pathology in Alzheimer’s disease: A clinicopathological prospective study. Acta Neurol Scand 139:76-81.

[12] Lee, et al. Effects of Alzheimer and Lewy body disease pathologies on brain metabolism. Ann Neurol. 91:853-863.

[13] Kantarci, et al. FDG PET metabolic signatures distinguishing prodromal DLB and prodromal AD. Neuroimage: Clinical 31:102754.

[14] Sasaki, et al. Neuromelanin magnetic resonance imaging of locus ceruleus and substantia nigra in Parkinson's disease. Neuroreport. 17:1215-8

[15] Schwarz, et al. T1-Weighted MRI shows stage-dependent substantia nigra signal loss in Parkinson's disease. Movement Disorders. 26:1633–38

[16] Keren, et al. Histologic validation of locus coeruleus MRI contrast in post-mortem tissue. Neuroimage, 113:235-245

Figures

Table 1. Demographic information for the AD/MCI groups with and without Lewy bodies used in this analysis. Data is presented as mean ± standard deviation unless noted otherwise. Two-tailed t-tests were used for group comparisons of all ages, nigral neuronal loss, Braak stage, education, CDR Global, MMSE, ADAS11, and Trails B from which P values are shown. AD – Alzheimer’s disease. MCI – Mild Cognitive Impairment. LB – Lewy bodies. MMSE – Mini-Mental State Exam. CDR – clinical dementia rating, ADAS – Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale.