1716

Relationships of oxidative stress markers in the brain with circulating sex hormones1Brigham and Women's Hospital/Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, United States, 2Brigham and Women's Hospital, Boston, MA, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Psychiatric Disorders, Spectroscopy, Oxidative Stress

Oxidative stress is implicated in multiple psychiatric and neurodegenerative conditions, differs by biological sex and covaries with circulating estrogens. However, limited knowledge exists on the association of brain markers of oxidative stress via glutathione (GSH) with circulating sex hormones. Therefore, we conducted brain magnetic resonance spectroscopy, assayed blood serum for circulating sex hormones, and measured brain GSH-sex hormones associations. We found that dorsolateral prefrontal cortex GSH relates to estradiol in women and men and anterior cingulate cortex GSH relates to estradiol, estrone, and total testosterone in women. This study highlights the importance of considering sex in GSH MRS studies.Oxidative stress (OS) is an imbalance between the production of reactive oxygen species and available antioxidant capacity, which can lead to RNA and DNA damage, and downstream damage to proteins and cells including from apoptosis, cellular senescence and telomere shortening; characteristics seen across multiple disorders including psychotic disorders, mood disorders, and dementia.1,2 Thus, there is great interest in examining OS as a mechanism in psychiatric disorders in the brain in vivo. Glutathione is an endogenous antioxidant and the most prevalent antioxidant in the brain. Multiple magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) studies have identified lower glutathione levels in the brain in depression, schizophrenia, anxiety, and bipolar disorders.2–5 However, others have found either higher levels or no difference in glutathione levels in the brain in these populations.2,3,6 Pre-clinical and peripheral studies suggest that oxidative stress differs by biological sex and covaries with circulating estrogens.7,8 There exists limited knowledge of the relationship between sex hormones, including estrogens, and MRS measures of glutathione in the brain, which we suggest may in part contribute to inconsistencies in the literature to date. Therefore, we aimed to test for sex differences and for associations of sex hormones with regional concentrations of glutathione in multiple brain regions.

Methods

Thirty-one participants (15 women and 16 men) were recruited and included individuals with and without a mood disorder, ages 35–61 (M=48, SD=9) years old. Due to the ongoing status of the study mood disorder status was not examined and beyond the scope of the current investigation but will be investigated in the future. Peripheral sex hormones were assayed from a fasted morning blood draw using liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC/MS/MS) and included estradiol/estrone, progesterone, and DHT/total/free testosterone. Imaging was performed on a clinical 7.0 Tesla MR scanner (Siemens Magnetom Terra) with a 32‐channel receiver head coil. T1-weighted images were acquired with a 3D magnetization-prepared-rapid-gradient-echo (MPRAGE) sequence (TR=2290ms, TE=2.95ms, voxel size=0.7×0.7×0.7 mm3) and were used to place each MRS voxel. Single-voxel MRS utilized a STEAM sequence (TR/TE/TM=3000ms/20ms/10ms, 128 averages). Voxels were positioned in the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex (ACC, voxel size=40x20x20mm3), ventromedial prefrontal cortex (VMPFC, voxel size=20x20x20mm3), and left DLPFC (voxel size=20x20x20mm3). Automated optimization included 3‐dimensional shimming, transmit gain, frequency adjustment, and water suppression. Manual shimming was performed to optimize the magnetic field homogeneity to a line width of <30Hz FWHM of the absolute water. Pre-processing was performed in OpenMRSLab including coil combination, frequency and phase correction, and eddy current correction and residual water removal9 and spectral fitting using LCModel software10, with a customized basis set of simulated spectra for 19 metabolites. Quality control included the following criteria: 1) a FWHM linewidth of the unsuppressed water spectrum <30Hz, 2) signal‐to‐noise ratio (SNR)>5, and 3) Cramer-Rao Lower Bound (CRLB) of NAA<5%. Relationships between central GSH with circulating sex hormones were tested using Pearson’s correlations. We assessed the influence of age in regression analyses. Significance was set at an alpha of p<0.05.

Results

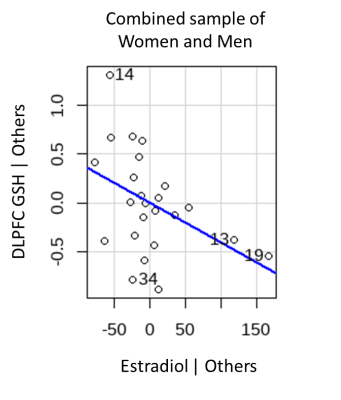

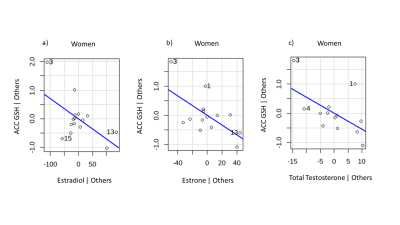

We observed a significant inverse correlation of DLPFC GSH with estradiol (r=-0.414, p=0.044, Figure X) in the combined sample of men and women. No significant effects emerged for relationships with ACC and VMPFC GSH with sex hormones. When controlling for age, the inverse relationship between DLPFC GSH with estradiol remained significant (p=0.043). No other significant effects emerged in regression models controlling for age in the combined sample of men and women. In women, DLPFC GSH was inversely correlated with total testosterone (r=-0.603, p=0.038, Figure X). When controlling for age, the effect of DLPFC GSH in relation to total testosterone was no longer significant. However, we observed significant inverse relationships of ACC GSH with estradiol (t=-2.50, p=0.028), estrone (t=-2.60, p=0.025), and total testosterone (t=-2.23, p=0.050). In men, no significant relationships emerged between GSH and any of the sex hormones.

Discussion

These results suggests that the DLPFC and ACC are key regions in which sex hormones related to levels of glutathione. In the combined sample of men and women, DLPFC GSH was inversely related to estradiol. The combined sample allowed for greater power in detecting relationships with GSH across a fuller range of estradiol levels, and thus, implicates the DLPFC as potential mechanistic target that may be more sensitive to antioxidant or estrogenic treatment strategies aimed at reducing oxidative stress in both men and women. In women, DLPFC GSH was inversely related to total testosterone; but, when controlling for age, ACC GSH was inversely related with estradiol, estrone, and total testosterone. Results in women have implications for differences in the OS-sex hormones relationship based on reproductive stage. Taken together, our results extend preclinical studies indicating sex differences in OS by showing sex-specific relationships of GSH with circulating sex hormones. However, results of this study should be interpreted with caution given the small sample size and warrant replication with further examination of reproductive stage.

Conclusions

Our results suggest that central GSH may be related to circulating sex hormones in women and men, particularly in the DLPFC and ACC in relation to estradiol, estrone, and total testosterone. Further, this study provides evidence that studies examining GSH using MRS should consider the effect of circulating sex hormones.

Acknowledgements

No acknowledgement found.References

References

1. Jiménez-Fernández S, Gurpegui M, Garrote-Rojas D, Gutiérrez-Rojas L, Carretero MD, Correll CU. Oxidative stress parameters and antioxidants in adults with unipolar or bipolar depression versus healthy controls: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2022 Oct 1;314:211–221. PMID: 35868596

2. Bottino F, Lucignani M, Napolitano A, Dellepiane F, Visconti E, Rossi Espagnet MC, Pasquini L. In Vivo Brain GSH: MRS Methods and Clinical Applications. Antioxidants [Internet]. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute; 2021 Sep [cited 2022 Nov 8];10(9):1407. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2076-3921/10/9/1407

3. Fisher E, Gillam J, Upthegrove R, Aldred S, Wood SJ. Role of magnetic resonance spectroscopy in cerebral glutathione quantification for youth mental health: A systematic review. Early Interv Psychiatry [Internet]. 2020 Apr [cited 2022 Nov 8];14(2):147–162. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7065077/ PMCID: PMC7065077

4. Kumar J, Liddle EB, Fernandes CC, Palaniyappan L, Hall EL, Robson SE, Simmonite M, Fiesal J, Katshu MZ, Qureshi A, Skelton M, Christodoulou NG, Brookes MJ, Morris PG, Liddle PF. Glutathione and glutamate in schizophrenia: a 7T MRS study. Mol Psychiatry [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2022 Nov 8];25(4):873–882. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7156342/ PMCID: PMC7156342

5. Godlewska BR, Near J, Cowen PJ. Neurochemistry of major depression: a study using magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Psychopharmacology (Berl) [Internet]. 2015 Feb 1 [cited 2022 Nov 8];232(3):501–507. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00213-014-3687-y

6. Soeiro-de-Souza MG, Pastorello BF, Leite C da C, Henning A, Moreno RA, Garcia Otaduy MC. Dorsal Anterior Cingulate Lactate and Glutathione Levels in Euthymic Bipolar I Disorder: 1H-MRS Study. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol [Internet]. 2016 Aug 1 [cited 2022 Nov 8];19(8):pyw032. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1093/ijnp/pyw032

7. Brunelli E, Domanico F, Russa D, Pellegrino D. Sex Differences in Oxidative Stress Biomarkers. Curr Drug Targets [Internet]. 2014 Jul 31 [cited 2022 Nov 7];15(8):811–815. Available from: http://www.eurekaselect.com/openurl/content.php?genre=article&issn=1389-4501&volume=15&issue=8&spage=811

8. Chang SH, Chang CH, Yang MC, Hsu WT, Hsieh CY, Hung YT, Su WL, Shiu JJ, Huang CY, Liu JY. Effects of estrogen on glutathione and catalase levels in human erythrocyte during menstrual cycle. Biomed Rep [Internet]. Spandidos Publications; 2015 Mar 1 [cited 2022 Nov 7];3(2):266–268. Available from: https://www.spandidos-publications.com/10.3892/br.2014.412

9. Rowland B, Mariano L, Irvine JM, Lin AP. OpenMRSLab: An open-source softward repository for Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy data analysis tools. 2016.

10. Provencher SW. Estimation of metabolite concentrations from localized in vivo proton NMR spectra. Magn Reson Med. 1993 Dec;30(6):672–679. PMID: 8139448

Figures