1715

Association of brain macrostructural changes and objective sleep measures in military service members after a remote mild traumatic brain injury1National Intrepid Center of Excellence,Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, Bethesda, MD, United States, 2Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, Bethesda, MD, United States, 3Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, Bethesda, MD, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Traumatic brain injury, Traumatic brain injury

In this study, we quantitated the size of white matter hyperintense (WMH), enlarged perivascular space (ePVS) and diffusion tensor imaging analysis along the perivascular space (DTI_ALPS) index in service members after a remote mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI), and associated them with objective sleep measures. There was no significant difference of the regional size of WMH, ePVS or hemispheric DTI_ALPS index between controls and mTBI. In mTBI participants, lifetime TBI/PCE events was associated amygdala-hippocampal complex ePVS load; and sleep arousal / awakening index was associated with temporal WMH load, periodic limb movement during sleep with basal ganglia WMH load.Introduction

It has been estimated that 50% - 80% of people with mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI) experience sleep wake disturbances1,2. Sleep is also important for physiological processes and plays a crucial role in the ability of the brain to clear metabolic wastes. Enlarged perivascular spaces (ePVS), which could represent a marker for reduced clearance of the glymphatic system, are visible in T1W and T2W magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)3. In this study, we quantitated brain white matter hyperintense (WMH) and ePVS to assess brain macrostructural changes; and used diffusion tensor imaging analysis along the perivascular space (DTI-ALPS)4 method to evaluate the movement of water molecules in the space around blood vessels by measuring the diffusion coefficient4; and associated the brain changes with sleep measures in service members (SMs) after mTBI. The goal of this study is to promote identification objective imaging markers for sleep disorders after TBI.Methods

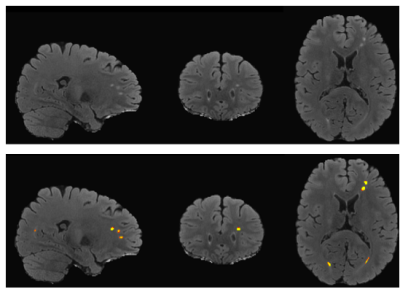

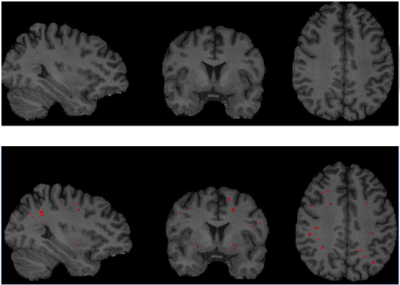

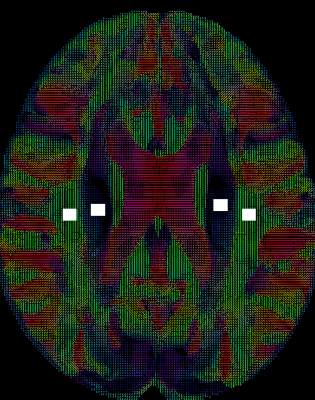

mTBI participants were recruited and selected from a larger cohort study at the National Intrepid Center of Excellence, WRNMMC. Diagnosis of TBI during enrollment occurred via a multi-layered structured interview process screening for every potential concussive event (PCE) during military deployments and across the entire lifetime, including childhood, using a modification of the Ohio State University TBI Identification (OSU TBI-ID) instrument5. mTBI was diagnosed as previously described6. We have included 416 male service members (age: 40.5±5.8 years old, time since injury =17.8 ±10.0 years) and 61 male controls (age: 36.1±7.9 years old). ePVS and WMH were segmented by using a deep learning algorithm with a convolutional auto-encoder and a U-shaped neural network for the 3-dimensional segmentation of WMH lesions on T2w FLAIR7 (Fig. 1) and ePVS on T1w8 mages (Fig. 2), respectively. Each regional WMH and ePVS loads, including the frontal, parietal, temporal, occipital and insular lobes, as well as the ePVS load in the thalamus, basal ganglia (BG) and amygdala-hippocampal complex (AHC) were normalized by use of total intracranial volume. DTI-ALPS index was calculated in both hemispheres using non-diffusion and diffusion-weighted MRI volumes (1000 s/mm2). The DTI-ALPS index is defined as follows 58: DTI–ALPS index = mean (Dxproj, Dxassoc) / mean_(Dyproj, Dzassoc), where Dxproj , Dxassoc, Dyproj, Dzassoc are for x, y, z axis diffusivity in projection fiber and association fiber) (Fig. 3). Higher DTI-ALPS index indicates better glymphatic function). Polysomnography (PSG) data was acquired during their overnight sleep. The sleep variables included: sleep stage architecture, including rapid eye movement (REM) stage and non-REM stage sleep, periodic limb movements (PLM) during sleep, oxygen saturation and airway indices, apnea-hypopnea index (AHI, the number of apneas or hypopneas recorded per hour of sleep). In addition, self-report scores, e.g. Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) CheckList – Civilian Version (PCL-C), neurobehavioral symptom inventory (NSI) were collected and used for regression and correlational analysis. General linear models were then applied to both hemispheric ALPS index, regional PVS volumes and WMH volumes fractions to calculate the main effect of group while controlling for covariate, i.e. age, body mass index, time since injury, average systolic and diastolic pressure, heart rate and time since the main episode of brain injury. Partial Pearson correlation was used to assess association between neuroimaging measures (DTI-ALPS index, WMH and ePVS loads), self-report symptomatic scores, PSG data in mTBI participants. Significance was set at p < 0.005 to correct for multiple comparisons.Results

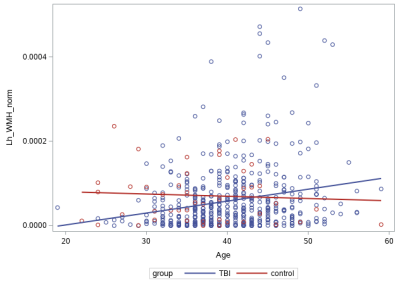

In mTBI, ePVS and WMH load positively correlated with age and BMI, but DTI-ALPS index reversely correlated with age; while in control, only ePVS load was found to correlate with age. In addition, elevated blood pressure (BP), particularly diastolic BP (p< 0.001), positively correlated with ePVS loads. There was no significant group difference (mTBI vs controls) of DTI-ALPS index and WMH and ePVS loads. In mTBI, lower left DTI-APLS had greater left hemispheric WMH load (p=0.02), and left hemispheric ePVS load correlated with WMH load (p=0.03). mTBI had greater yearly rate of increased left WMH load than control (p=0.03) (Fig.4). For correlational analysis in mTBI subjects, the WMH load of the right temporal lobe positively correlated with sleep REM latency (p=0.004) and arousal / awakening index (p=0.002) (Fig. 5A); and the WMH load of the left BG correlated with the total number of PLM (p=0.004). The ePVS load of the right thalamus positively correlated with the airway index during sleep PLM; and the ePVS load of the right AHC correlated positively with the total TBI count (p=0.002) and the total PCE count (p=0.0002) (Fig. 5B).Discussion / Conclusions

Compared to controls, no difference of WMH, ePVS, or DTI-ALPS was found in mTBI SMs after a remote brain injury. The finding of no difference of WMH load between mTBI and control is consistent with our previous report9. We did not find DTI-ALPS index useful in assessing sleep disturbances. The findings of association of higher burden of WMH and ePVS and objective PSG measures, as well as the total counts of previous TBI and PCE incidence suggest neuroimaging measures can be beneficial in predicting the sleep disorders in mTBI after a remote brain injury and their long-term outcomes caused by heterogeneous injury mechanisms.Acknowledgements

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this abstract are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy of the Department of Defense or the U.S. Government.References

1. Mathias JL, Alvaro PK. Prevalence of sleep disturbances, disorders, and problems following traumatic brain injury: A meta-analysis. Sleep Med. 2012;13(7):898-905. doi:10.1016/j.sleep.2012.04.006

2. Grima N, Ponsford J, Rajaratnam SM, Mansfield D, Pase MP. Sleep disturbances in traumatic brain injury: A meta-analysis. J Clin Sleep Med. 2016;12(3):419-428. doi:10.5664/jcsm.5598

3. Wardlaw JM, Smith EE, Biessels GJ, et al. Neuroimaging standards for research into small vessel disease and its contribution to ageing and neurodegeneration. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12(8). doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(13)70124-8

4. Taoka T, Masutani Y, Kawai H, et al. Evaluation of glymphatic system activity with the diffusion MR technique: diffusion tensor image analysis along the perivascular space (DTI-ALPS) in Alzheimer’s disease cases. Jpn J Radiol. 2017;35(4):172-178. doi:10.1007/s11604-017-0617-z

5. Walker WC, Carne W, Franke LM, et al. The Chronic Effects of Neurotrauma Consortium (CENC) multi-centre observational study: Description of study and characteristics of early participants. Brain Inj. 2016;30(12):1469-1480. doi:10.1080/02699052.2016.1219061

6. Kay T, Harrington DE, Adams R, et al. Definition of mild traumatic brain injury. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 1993;8(3):86-87. doi:10.1097/00001199-199309000-00010

7. Tsuchida, A. V, Verrecchia P, Boutinaud S, Debette C, Joliot T and M. Early detection of white matter hyperintensities using SHIVA-WMH detector. In: Organization of Human Brain Mapping. ; 2022.

8. Boutinaud P, Tsuchida A, Laurent A, et al. 3D Segmentation of Perivascular Spaces on T1-Weighted 3 Tesla MR Images With a Convolutional Autoencoder and a U-Shaped Neural Network. Front Neuroinform. 2021;15. doi:10.3389/fninf.2021.641600

9. Riedy G, Senseney JS, Liu W, et al. Findings from Structural MR Imaging in Military Traumatic Brain Injury. Radiology. Published online 2016. doi:10.1148/radiol.2015150438

Figures