1714

Altered resting state functional connectivity in high-contact sports1Radiology, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, United States, 2Medical Biophysics, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada, 3Neurological Surgery, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA, United States, 4Psychology, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA, United States, 5Neurosurgery, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, United States, 6Bioengineering, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Traumatic brain injury, Brain Connectivity, high-contact sports, resting state functional connectivity

Repetitive head impact exposure during contact sports may increase risk of cognitive decline and neurodegenerative disease. We compared resting state functional connectivity (rsFC) networks between a group of high-contact collegiate PAC-12 athletes and a low-contact group from two institutions (groups comprised athletes of multiple sports and both sexes). A community chi-squared analysis evaluated differences in connectivity within/between 12 brain networks comparing high- vs. low-contact sports. Across both institutions, rsFC in the high-contact cohort was significantly increased (hyperconnectivity) between dorsal attention and default mode network (DMN), and significantly decreased (hypoconnectivity) between dorsal attention and frontoparietal networks, compared to the low-contact cohort.Repetitive head trauma is common in high-contact sports such as football. Repeated head impacts may carry significant risks: increasing evidence has suggested persistent neurological impairments,1 cognitive and memory decline,2 and higher risk for neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease3 and chronic traumatic encephalopathy.4 Resting state functional MRI (rsfMRI) is sensitive to neurological impairments and functional changes. The goal of this work was to investigate whether exposure to high-contact sports causes changes of resting state functional connectivity (rsFC) compared to athletes in low-contact sports.

Methods

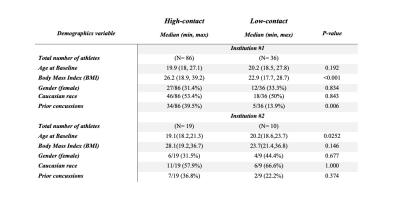

Subjects. 86 high-contact (27 female, 59 male) and 36 low-contact athletes (12 female, 24 male) from PAC-12 athletic teams from institution #1 were scanned before the start of their sport season. Institution #1 sports included (1a) high-contact: football, lacrosse, rugby, and wrestling, (1b) low-contact: archery, badminton, golf, rowing, and tennis. Another 19 high-contact athletes (6 female, 13 male), and 10 low-contact individuals (5 female, 5 male) from institution #2 were scanned before the start of their sport season. Institution #2 sports included (2a) high-contact: football and lacrosse, (2b) low-contact: rowing, tennis, and swimming. Demographics variables were compared between the two athlete groups using the Wilcoxon rank-sum and Fisher’s exact tests in both institutions (Fig.1).

Imaging data acquisition and analysis. Imaging at institution #1 was performed on a 3T GE-MR750 scanner with a 32-channel head coil. T1-weighted MPRAGE anatomical images were acquired (sagittal ME-MPRAGE, TR=7.9ms, six TEs from 1.6 to 9.6ms, 1mm isotropic, 5.1min). Resting state functional MRI was performed using a whole-brain resting state fMRI sequence of 1000 volumes, with 20 reverse field polarity images for distortion correction, TR=490ms, TE=30ms, multi-band acceleration 6, 3x3x3.5mm isotropic, 8min). At institution #2 imaging was conducted in a 3T Siemens Magnetom Prisma. T1-weighted multi-echo anatomical scan (sagittal TFL-MGH-multiecho, TR=2840ms, six TEs from 2.31ms to 13.51ms, 1mm isotropic, 5.05 min). rsfMRI was performed using a whole brain resting state fMRI sequence of 1000 volumes, with 20 reverse field polarity images, TR=490ms, TE=30ms, multi-band acceleration 6, 3x3x3.5mm isotropic, 8 min). All subjects were instructed to close their eyes but remain awake during the rsfMRI.

Resting state data were preprocessed using the DCAN-Labs / abcd-hcp-pipeline,5 independently for each institution. Briefly, this pipeline performs FreeSurfer segmentations of T1 images, followed by standard preprocessing of rsfMRI data. rsfMRI frames with high frame displacement (FD>0.2) were discarded. Linear Pearson correlations between the motion-corrected, parcellated time series6 for each cortical region were used to generate functional connectivity matrices for each subject. A linear model was applied to assess rsFC differences between sports (high-contact vs. low-contact) on each functional connection, including the covariates of age and gender. All nodes were arranged by their associated twelve functional networks. A community chi-squared analysis (CCA) was used to correct for multiple comparisons by examining whether statistical effects are preferentially distributed within or between functional networks.7 CCA identifies interesting within/between network effects from a set of mass univariate tests by taking a binarized matrix of significance tests (output of the aforementioned linear model for rsFC differences between sports) and determining whether those tests occur significantly greater than chance within/between specific communities (networks), which are based on the published community structure.6 We used 1,000 permutations, and the false-discovery rate threshold was 0.05 divided by 12, the number of networks that the nodes are being clustered to. The output of CCA shows a higher proportion of significant connections within/between each of these network pairs.

Results

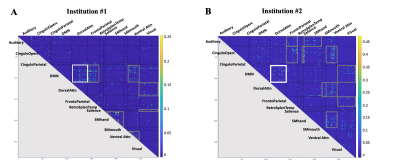

For our institution #1 cohort, we identified 7 brain network pairs with significantly increased connectivity (hyperconnectivity) in high- compared to low-contact sports (Fig 2.A). For the institution #2 cohort, we identified 11 network pairs with significant hyperconnectivity in high- vs. low-contact sports (Fig 2.B). Among these network pairs with hyperconnectivity, one network pair, the default mode network (DMN) and dorsal attention network, was hyperconnected to one another in both cohorts.

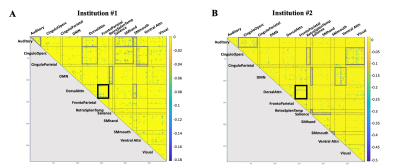

For the institution #1 cohort, we found 11 network pairs with significantly reduced connectivity (hypoconnectivity) in high- compared to low-contact sports (Fig 3.A). For the institution #2 cohort, 9 networks pairs had significant hypoconnectivity in high- vs. low-contact sports (Fig 3.B). Among these, the dorsal attention – frontoparietal network pair exhibited hypoconnectivity to one another in both institutions.

Discussion and Conclusion

Our results suggest that exposure to high-contact sports may be associated with an increase in the functional connectivity between dorsal attention network and DMN, as well as decreased connectivity of dorsal attention and frontoparietal networks. It is possible that traumatic impacts shift internetwork connectivity, such that there is less connectivity between the attention and frontoparietal associative networks, resulting in more connectivity between the attention and DMN These results were validated in two independent cohorts, suggesting that rsFC may reflect functional changes in the high-contact group. Our ongoing work will correlate these resting state changes with neurocognitive measures and evaluate longitudinal changes of network connectivity.

Acknowledgements

This research was conducted with funding from General Electric Healthcare and the Pac-12 Conference’s Student Athlete Health and Well-Being Initiative.References

1. Bazarian, Jeffrey J., et al. "Persistent, long-term cerebral white matter changes after sports-related repetitive head impacts." PloS one 9.4 (2014): e94734.

2. Strain, Jeremy F., et al. "Imaging correlates of memory and concussion history in retired National Football League athletes." JAMA neurology 72.7 (2015): 773-780.

3. Lehman, Everett J., et al. "Neurodegenerative causes of death among retired National Football League players." Neurology79.19 (2012): 1970-1974.

4. McKee, Ann C., et al. "Chronic traumatic encephalopathy in athletes: progressive tauopathy after repetitive head injury." Journal of Neuropathology & Experimental Neurology 68.7 (2009): 709-735.

5. https://github.com/DCAN-Labs/abcd-hcp-pipeline

6. Gordon, Evan M., et al. "Generation and evaluation of a cortical area parcellation from resting-state correlations." Cerebral cortex 26.1 (2016): 288-303.

7. https://github.com/DCAN-Labs/CommunityChiSquaredAnalysis

Figures