1712

Assessment of dynamic shear strain in the brain caused by mechanical transients using multi-scale MR elastography

Yuan Le1, Jun Chen1, Yi Sui1, Phillip J. Rossman1, Armando Manduca1, Kevin J. Glaser1, John Huston III1, Richard L. Ehman1, and Ziying Yin1

1Radiology, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN, United States

1Radiology, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Traumatic brain injury, Traumatic brain injury, Motion encoding gradient, transient motion

To study how the human brain moves and deforms under a sub-injury level transient impact, we tested the feasibility of measuring in-vivo brain transient motion resulting from a small amplitude impact using the multi-scale MR Elastography technique. Transient motion was encoded by wavelet-based motion encoding gradients at two wavelet scales plus a scaling function, and displacement was calculated using the inverse Haar transform. Brain motion over a wide frequency range was detected and was found to be consistent with previous results from a much higher impact.Introduction

Subconcussive, repetitive head impacts (RHI) sustained in contact sports is a growing public health issue. To elucidate RHI injury mechanisms, many efforts seek to study how exposure to head impacts affects brain motion. Quantitative studies have been performed to measure the brain’s response to head impact with animal, cadaver, and simulation models1-4. Though much has been learned about brain mechanics and the resulting tissue damage through these destructive and simulation studies, there still exists very little data about how the human brain actually reacts during impact. Many motion-sensitive MRI techniques have been developed to attempt to fill in this gap, such as MR tagging5,6 and MR elastography (MRE)7,8. Standard MRE uses harmonic motion to measure the in-vivo brain mechanics, however, the use of a mechanical transient may offer certain advantages as it more closely resembles the pattern of a real impact. While a transient impulse has been used for MRE mechanical excitation before, with standard MRE there is a trade-off between broadband motion coverage and sensitivity to each possible motion frequency, which can be very challenging even with some a priori knowledge about motion frequency9.To address this problem, we developed a new encoding scheme – multi-scale MRE – to efficiently detect broadband transient motion10. In this study, we applied this technique to the human brain and explored the feasibility of measuring the in-vivo brain displacements resulting from a small amplitude transient impact.Methods

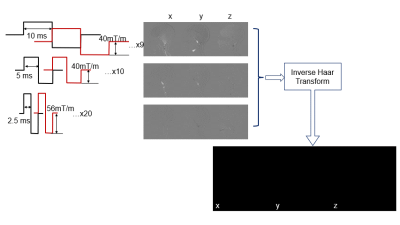

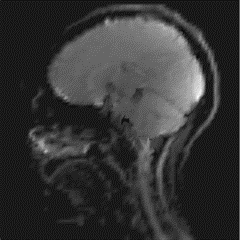

A healthy volunteer was scanned at a 3T clinical scanner (MAGNETOM Skyra, Siemens Healthcare, Erlangen, Germany). This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board. Informed consent was obtained. One cycle of a 90 Hz motion waveform was generated by a pneumatic driver (Resoundant Inc. Rochester MN, USA) at the onset of each TR. Figure 1 shows the location of the driver. Images were acquired using a multi-scale MRE sequence based on single-shot spin-echo EPI10. Ten consecutive sampling windows of 10 ms were sampled with a total time duration of 100 ms (Figure 2). 20 ms bipolar MEG detected the difference between the DC value of consecutive windows, cumulative sum of the acquired phase difference were used as scaling function elements. In addition 10 and 5 ms MEG were used as the two wavelet scales. The gradient amplitude was 40, 40, and 56 mT/m respectively. The TR/TE was 1000/55 ms. One sagittal slice was acquired with a slice thickness of 3 mm and in-plane resolution of 3x3 mm2. The total scan time was about 6 minutes. Displacement maps were calculated using the inverse Haar Transform and motion trajectories were plotted for each voxel. The 3D motion of each voxel was also projected onto the magnitude images for animated visualization of brain motion during the transient impact.Results and Discussion

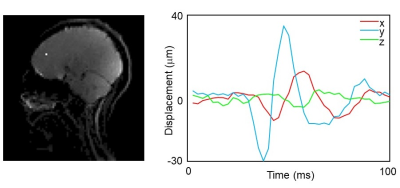

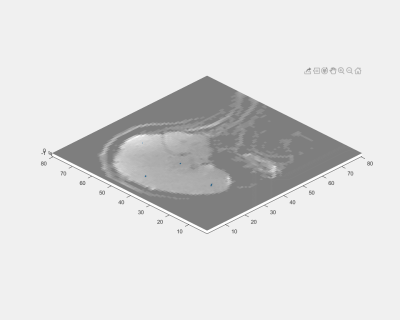

Figure 2 shows the phase difference maps from each MEG scale as well as the scaling function. The bulk motion of the head was found dominant in the x- and y-direction while the shear wave was found in all three directions. Most of the detected motion signal was found with MEG length of 20 ms and 10 ms. Figure 3 shows the displacement curve at one example voxel (white dot). From the figure, the corresponding voxel first vibrated at a higher frequency and amplitude, then both the amplitude and frequency decreased during the 100 ms time window. The peak frequency during the whole 100 ms window was at about 30 Hz and the peak amplitude was around 35 mm. The peak frequency of 30 Hz may be a result of the combined inherent natural frequency of the human head, the passive driver system, and the scanner table. Figure 4 shows the motion trajectory of four example voxels in the brain. The trajectories were very close to the ‘figure-8’ trajectory that was documented in previous studies found in the literature9.Figure 5 animates how the brain moves and deforms under a sub-injury level transient impact to the back of the head. The motion was amplified by 500 times. During the input induced by the brain driver, the initial bulk movement of the brain was toward the contrecoup location (i.e., front) with subsequent movement toward the coup location (i.e., back), which mimics the classic coup and contrecoup injury pattern. Of note, when the brain first encountered the inner skull, shear motion was generated in all three directions. And then the brain quickly moved back, with the shear wave starting to propagate through the whole brain.

Conclusions

This study demonstrated the feasibility of using the proposed multi-scale MRE technique to measure broadband transient motion in the brain in vivo. Knowledge of in vivo brain motion under the transient impact would help elucidate the mechanisms by which head trauma causes hemorrhage, cerebral contusions, and diffuse axonal injury. Future studies will focus on optimizing the imaging protocol to acquire 3D volume data with multiple slices within a clinically feasible time.Acknowledgements

This work is supported by grants from the NIH (R01 EB001981 and R01 NS113760). We also gratefully acknowledge the contributions of Dr. Bradley D. Bolster and Dr. Stephan Kannengiesser at Siemens Healthcare to this work.References

- Xiong, Y., Mahmood, A. & Chopp, M. Animal models of traumatic brain injury. Nature Reviews Neuroscience 14, 128-142, doi:10.1038/nrn3407 (2013).

- Hardy, W. N. et al. Investigation of Head Injury Mechanisms Using Neutral Density Technology and High-Speed Biplanar X-ray. Stapp car crash journal 45, 337-368 (2001).

- Zou, H., Schmiedeler, J. P. & Hardy, W. N. Separating brain motion into rigid body displacement and deformation under low-severity impacts. J Biomech 40, 1183-1191, doi:10.1016/j.jbiomech.2006.06.018 (2007).

- Griffths, E. & Budday, S. Finite element modeling of traumatic brain injury: Areas of future interest. Current Opinion in Biomedical Engineering, 100421 (2022)

- Ji, S., Zhu, Q., Dougherty, L. & Margulies, S. S. In vivo measurements of human brain displacement. Stapp car crash journal 48, 227-237 (2004).

- Bayly, P. V. et al. Deformation of the human brain induced by mild acceleration. Journal of neurotrauma 22, 845-856, doi:10.1089/neu.2005.22.845 (2005).

- Yin, Z. et al. In vivo characterization of 3D skull and brain motion during dynamic head vibration using magnetic resonance elastography. Magn Reson Med 0, doi:10.1002/mrm.27347 (2018).

- Badachhape, A. A. et al. The relationship of three-dimensional human skull motion to brain tissue deformation in magnetic resonance elastography studies. J Biomech Eng 139, DOI: 10.1115/1111.4036146., doi:10.1115/1.4036146 (2017).

- McCracken, P. J., Manduca, A., Felmlee, J. & Ehman, R. L. Mechanical transient-based magnetic resonance elastography. Magn Reson Med 53, 628-639, doi:10.1002/mrm.20388 (2005).

- Le, Y. et al. in Joint Annual Meeting ISMRM-ESMRMB Vol. 31 (London, England, UK, 2022).

Figures

Figure 1. The location of the MRE passive driver.

Figure 2 A series of phase difference maps (gray scale movies) were

acquired at each MEG level (from top to bottom: 9 phase offsets from 20ms

scaling function alternative, 10 from 10ms, and 20 from 5ms). Final

displacement maps are shown as the pseudo-color wave movie.

Figure 3. Displacement curves at one example voxel (the white dot).

Figure 4. Displacement trajectories at 4 representative

voxels.

Figure 5. Amplified brain motion (x500) under a sub-injury transient

impact to the back of the head. The through-slice motion was encoded as the

transparency of the voxel.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.58530/2023/1712