1708

The effects of repetitive head impact exposure on cerebrovascular reactivity in middle and high-school athletes1Radiology, Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, WI, United States, 2Neurosurgery, Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, WI, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Traumatic brain injury, fMRI, Cerebrovascular reactivity, Breath hold

Cerebrovascular reactivity (CVR) can provide a marker of vascular injury. The effects of repetitive head impact exposure (RHIE) during contact sports remains to be fully elucidated. We investigated the effect of sport, time, and their interaction on CVR in contact sport (CS) and non-contact sport (NCS) middle school and high school athletes. There was a significant effect of time and a significant interaction effect between contact group and time on CVR with CVR decreasing pre to post season in the NCS group but remaining unchanged in the CS group.

Introduction

Cerebrovascular reactivity (CVR) measures the blood vessels’ response to a vasoactive stimulus and can provide a marker of vascular injury. A number of studies have investigated the effects of mild traumatic brain injury on cerebrovascular reactivity (CVR). For example, studies have shown CVR is increased in the acute phase following TBI1,2 followed by decreases continuing months after and potentially into the chronic state3. Repetitive head impact exposure (RHIE), without concussion, during contact sports can also have harmful neurocognitive effects4-6. The effects of RHIE on CVR have been underexplored. We evaluated the effect of sport, time, and their interaction in contact sport (CS) and non-contact sport (NCS) middle school and high school athletes imaged pre- and post-season using CVR measured with an advanced multiband, multi-echo (MBME) MRI sequence.Methods

Thirty-six male, non-concussed, United States middle school and high school contact sport (CS, N=15) and non-contact sport (NCS, N=21) athletes underwent MRI scans before and after their respective seasons. Overall, 11 CS and 14 NCS athletes completed both preseason and follow-up postseason scans.Imaging was performed on a 3T GE Premier scanner. A T1-weighted MPRAGE anatomical image was acquired, followed by a gradient echo multiband, multi-echo (MBME) breath hold (BH) task fMRI scan with the following parameters: TR/TE=1000/11,30,49ms, FOV=24cm, matrix size=80x80 with slice thickness = 3mm (3x3x3mm voxel size), 11 slices with multiband factor=4 (44 total slices), FA=60°, partial Fourier factor=0.85, and in-plane acceleration (R)=2. The BH task consisted of 66 s of paced breathing, followed by four cycles of 24 s of paced breathing, 16s of BH on expiration, and 16 s of self-paced recovery breathing. Scans ended with an additional 30s of paced breathing7. The paced breathing portions consisted of alternating 3s inspiration and expiration blocks. A short, reversed polarity MBME scan was also collected to allow for image distortion correction.

Data was analyzed using a combination of AFNI and FSL. First, the anatomical MPRAGE image was coregistered to Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) space. Then, the first-echo functional data was volume registered to the first volume. Subsequent echoes were registered using the transformation matrices from the first echo. Image distortion was corrected using topup. The three echoes were then combined using the -weighted approach8 and denoised using multi-echo independent component analysis (ME-ICA)9-11 by regressing non-BOLD independent components out of the combined ME data. The denoised MBME dataset was then registered to the MPRAGE image and registered to MNI space using the anatomical transformations computed above.

The BH response was evaluated using a general linear model with 3dDeconvolve in AFNI. After 3dDeconvolve, a restricted maximum likelihood model (3dREMLfit) was used to model temporal autocorrelations in the data. BH regressors were generated by convolving a square wave with the respiration response function12 and shifting the regressor from −8s to 16s in steps of 2s. For each voxel, the regressor that resulted in the highest positive t-score was chosen. CVR was calculated as the percent signal change of the BH response.

Linear mixed-effects models were fit using 3dLMEr in AFNI to test the effects of time (pre- to post-season difference), contact group (CS vs. NCS), and group-by-time interactions in CVR. Age, BMI, and concussion history were included as covariates. Post-hoc general linear tests were performed to compare across time for each group individually and across groups at each time. Multiple comparisons were controlled for using a cluster size correction technique and 3dClustSim in AFNI (p < 0.05, α < 0.05).

Results

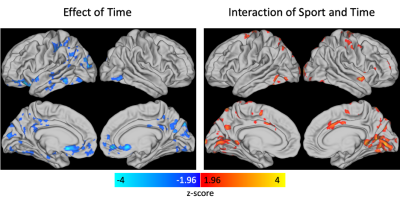

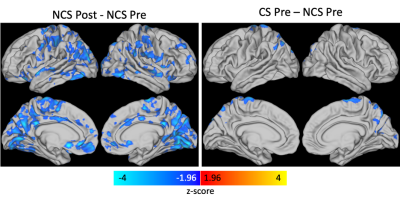

Results from the linear mixed effects model showed there was a significant effect of time and a significant interaction effect between contact group and time with clusters centered in the primary visual cortex (Figure 1). Post-hoc analyses (Figure 2) revealed the time effect was driven by a largely global significant decrease in CVR from post- to pre-season in the NCS group with clusters encompassing visual cortex, components of the default mode network (posterior cingulate cortex, precuneus, anterior cingulate cortex), motor cortex, and insula. A significant decrease in CVR was observed between CS and NCS groups at the preseason scan in the superior visual cortex, precuneus, and motor cortex.Discussion/Conclusions

Changes in CVR have been observed in female soccer players compared to a NCS control group with CVR decreasing post-season vs. preseason in athletes with more head acceleration events13. Another study demonstrated regionally decreased CVR in football players mid- and post-season compared to preseason14. Interestingly, in this study, we did not observe significant changes pre- to post-season in the CS group but did find significant decreases in CVR in the NCS group. It is possible there are competing effects with overall sport activity and collisions causing opposite effects on CVR. Thus, additional research is needed linking these findings to clinical measures and/or head impact telemetry or accelerometer measurements.Acknowledgements

No acknowledgement found.References

1. Wang R, Poublanc J, Crawley AP, Sobczyk O, Kneepkens S, McKetton L, Tator C, Wu R, Mikulis DJ. Cerebrovascular reactivity changes in acute concussion: a controlled cohort study. Quant Imaging Med Surg 2021;11(11):4530-4542.

2. Mutch WAC, Ellis MJ, Ryner LN, McDonald PJ, Morissette MP, Pries P, Essig M, Mikulis DJ, Duffin J, Fisher JA. Patient-Specific Alterations in CO2 Cerebrovascular Responsiveness in Acute and Sub-Acute Sports-Related Concussion. Frontiers in neurology 2018;9:23.

3. Haber M, Amyot F, Kenney K, Meredith-Duliba T, Moore C, Silverman E, Podell J, Chou YY, Pham DL, Butman J, Lu H, Diaz-Arrastia R, Sandsmark D. Vascular Abnormalities within Normal Appearing Tissue in Chronic Traumatic Brain Injury. Journal of neurotrauma 2018;35(19):2250-2258.

4. Stern RA, Riley DO, Daneshvar DH, Nowinski CJ, Cantu RC, McKee AC. Long-term consequences of repetitive brain trauma: chronic traumatic encephalopathy. PM & R : the journal of injury, function, and rehabilitation 2011;3(10 Suppl 2):S460-467.

5. Roby PR, Duquette P, Kerr ZY, Register-Mihalik J, Stoner L, Mihalik JP. Repetitive Head Impact Exposure and Cerebrovascular Function in Adolescent Athletes. Journal of neurotrauma 2021;38(7):837-847.

6. Slobounov SM, Walter A, Breiter HC, Zhu DC, Bai X, Bream T, Seidenberg P, Mao X, Johnson B, Talavage TM. The effect of repetitive subconcussive collisions on brain integrity in collegiate football players over a single football season: A multi-modal neuroimaging study. Neuroimage Clin 2017;14:708-718.

7. Cohen AD, Jagra AS, Visser NJ, Yang B, Fernandez B, Banerjee S, Wang Y. Improving the Breath-Holding CVR Measurement Using the Multiband Multi-Echo EPI Sequence. Front Physiol 2021;12(97):619714.

8. Posse S, Wiese S, Gembris D, Mathiak K, Kessler C, Grosse-Ruyken ML, Elghahwagi B, Richards T, Dager SR, Kiselev VG. Enhancement of BOLD-contrast sensitivity by single-shot multi-echo functional MR imaging. Magnetic resonance in medicine : official journal of the Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine / Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine 1999;42(1):87-97.

9. Kundu P, Brenowitz ND, Voon V, Worbe Y, Vertes PE, Inati SJ, Saad ZS, Bandettini PA, Bullmore ET. Integrated strategy for improving functional connectivity mapping using multiecho fMRI. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2013;110(40):16187-16192.

10. Kundu P, Inati SJ, Evans JW, Luh WM, Bandettini PA. Differentiating BOLD and non-BOLD signals in fMRI time series using multi-echo EPI. NeuroImage 2012;60(3):1759-1770.

11. DuPre E, Salo T, Markello R, Kundu P, Whitaker K, Handwerker D. ME-ICA/tedana: 0.0.6: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.2558498. 2019.

12. Birn RM, Smith MA, Jones TB, Bandettini PA. The respiration response function: the temporal dynamics of fMRI signal fluctuations related to changes in respiration. NeuroImage 2008;40(2):644-654.

13. Svaldi DO, McCuen EC, Joshi C, Robinson ME, Nho Y, Hannemann R, Nauman EA, Leverenz LJ, Talavage TM. Cerebrovascular reactivity changes in asymptomatic female athletes attributable to high school soccer participation. Brain Imaging Behav 2017;11(1):98-112.

14. Champagne AA, Coverdale NS, Nashed JY, Fernandez-Ruiz J, Cook DJ. Resting CMRO2 fluctuations show persistent network hyper-connectivity following exposure to sub-concussive collisions. Neuroimage Clin 2019;22:101753.