1706

A longitudinal neuroimaging study in mice on the effects of chronic high altitude exposure and repetitive traumatic brain injury1Department of Radiology and Radiological Sciences, Uniformed Services University, Bethesda, MD, United States, 2The Henry M. Jackson Foundation for the Advancement of Military Medicine, Bethesda, MD, United States, 3Department of Pharmacology and Molecular Therapeutics, Uniformed Service University, Bethesda, MD, United States, 4Georgia Cancer Center, Augusta University, Augusta, GA, United States, 5Department of Anatomy and Neurobiology, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, United States, 6Department of Anatomy, Physiology and Genetics, Uniformed Service University, Bethesda, MD, United States, 7Graduate Program in Neuroscience, Uniformed Service University, Bethesda, MD, United States, 8Department of Pathology, Uniformed Service University, Bethesda, MD, United States, 9National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases, NIH, Bethesda, MD, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Traumatic brain injury, Preclinical, hypobaria, hypoxia, DTI, PET/CT, cerebral blood flow

Chronic exposure to high altitude (HA) can lead to maladaptive physiological and pathological changes, resulting in an increased risk for neurological impairment. Whether the occurrence of mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI) at HA exacerbates neurobehavioral deficits remains uncertain. A series of experiments was conducted to test the impact of mTBI in the context of HA using established models of repetitive close head injury and simulated HA (5000m). A longitudinal study design was applied to identify the effects of chronic HA exposure (12 weeks) and mTBI in mice on neurobehavioral and neuroimaging biomarkers using PET and MRI.Introduction

Exposure to high altitude (HA), ≥ 2500m above sea level (SL), induces a hypobaric and hypoxic environment that can induce acute mountain sickness and high-altitude cerebral edema1,2. These conditions are associated with a wide spectrum of neurological symptoms including headaches, visual disruptions, sleep disturbances and cognitive dysfunction3-6. Our group has shown7 that subacute and chronic HA exposure in mice leads to cognitive deficits and abnormal MRIs, suggesting that HA promotes neurovasculature and white matter remodeling. Recent studies suggest a higher incidence and a more pronounced neurological impact of TBI at HA relative to SL8-10. Despite these reports, there is ongoing debate as to whether TBI exposure concomitant to or following HA exposure results in neurological deficits relative to either condition alone11,12.Methods

Ninety C57BL/6J male mice (Jackson Laboratories) were randomly assigned to control, SL and simulated HA (5000 meters in a hypobaric chamber) experimental groups. After 12 weeks at either HA or SL, the animals were randomized to the mTBI, three closed head injuries every 24 hours, or Sham groups. Behavioral testing was assessed 12 weeks post HA and 5-7 days following the final injury. Imaging occurred following completion of behavioral testing on day 9 following the final injury.Memory impairment was assayed using novel object recognition, and contextual and cued fear memory recall, with motor function screened in an open field. For PET/CT imaging the animals were injected intraperitoneally with approximately 0.5 mCi of [18F] FDG. The PET images were acquired using Siemens Inveon preclinical scanner (Erlangen, Germany), 45 minutes after the uptake (30 minutes awake and 15 minutes under anesthesia using 1–2% isoflurane for maintenance, in 100% O2 at 2 L/minutes).

MRI experiments were conducted using a 7T Bruker Biospec 70/20 (Billerica, MA). Animals were anesthetized with a mixture of 1-2% of isoflurane and medical air. The multi-echo 2D RARE and relaxation maps were used to assess injury, structural changes, and edema/inflammation progression tracking. Fractional anisotropy (FA) and trace (TR) maps calculated from 3D single shot DTI-EPI were used to assess inflammation and white matter integrity. Pseudo-continuous arterial spin labeling with EPI readout was used to compute relative cerebral blood flow (CBF) maps. A 2D RARE sequence was used to compute magnetization transfer ratio (MTR) maps.

The PET and MRI data were analyzed using either a voxel-based analysis (VBA) or region of interest (ROI) analysis. The Advanced Normalization Tools (ANTs) v2.313 was used to perform all registration steps.

Results

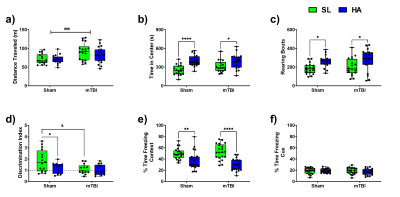

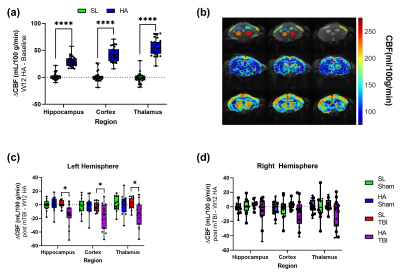

The total distance traveled was markedly increased in animals exposed to the mTBI (Figure 1a). HA exposure altered the parameters of exploration in the open field, time in center (Figure 1b) and number of rearing bouts (Figure 1c). HA and mTBI exposed mice reduced the normal preference of animals to explore a novel object over a familiar object (Figure 1d). Contextual fear memory was robustly reduced in HA exposed mice (Figure 1e). The magnitude of the effect of altitude was larger in the context of mTBI. Cued fear memory was not adversely affected in mice exposed to HA or mTBI (Figure 1f).Chronic HA exposure led to widespread changes in CBF with the Cortex, Hippocampus and Thalamus, while repetitive mTBI had a more targeted effect (Figure 2). HA-mTBI animals exhibited a consistent reduction in CBF in the ipsilateral hemisphere (Figure 2c) while no significant changes occurred in the contralateral hemisphere (Figure 2d).

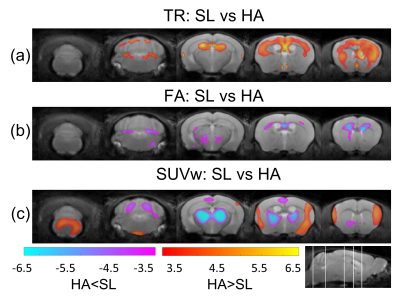

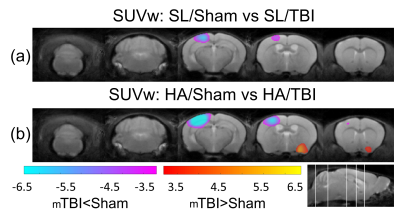

The significant changes in cluster level analysis are shown in the statistic parametric maps for the 12 weeks HA (Figure 3), where TR is increased (Figure 3a), FA is decreased (Figure 3b), and SUVw shows regions of increase and decrease in HA animals (Figure 3c). At the post-mTBI timepoint, a significant cluster is observed for SUVw near the site of injury, with a significant decrease in the SL-mTBI compared to SL-Sham (Figure 4a) and a decrease for HA-mTBI relative to HA-Sham (Figure 4b) animals.

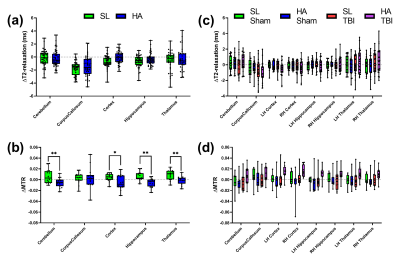

Figure 5 shows the results of changes in T2-relaxation time and MTR from baseline to 12 weeks and from 12 weeks to the post-mTBI assessment. T2-relaxation time values were elevated in the cortex of HA animals compared to SL (p=0.05) and no significant differences were observed from 12 weeks to post-mTBI. Overall MTR values decreased from baseline to 12 weeks and didn’t change significantly post-mTBI.

Summary

The data confirm that 12 weeks of HA exposure evoked cognitive deficits, manifesting as decreased contextual fear memory and impaired discrimination of novel objects. However, no synergistic effects of mTBI on HA associated cognitive dysfunction was apparent. CBF was markedly increased following HA exposure, as was global brain volume and MTR and trace across all regions suggesting widespread tissue damage despite the lack of overt histopathology (not shown here). FA and SUVs were decreased overall with HA exposure, indicative of white matter degeneration. In contrast with the compensatory increase in CBF observed following HA just prior to mTBI, there was a striking reduction in ipsilateral CBF for HA-mTBI animals two weeks post injury. Such alterations may lead to greater pathology overtime and increase the risk for significant neurological impairment and behavioral deficits.Acknowledgements

The opinions or assertions contained herein are the private ones of the author/speaker and are not to be construed as official or reflecting the views of the Department of Defense, the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences or any other agency of the U.S. Government.

This work was funded by the U.S. DOD in the Center for Neuroscience and Regenerative Medicine, U.S. Department of Defense Program Project 308430 USUHS, and Department of Radiology and Radiological Sciences at USUHS. The authors would like to thank the scientists and staff of the Biomedical Research Imaging Core of the Uniformed Services University for their expertise and support of our project. We are incredibly grateful for the invaluable contribution of Dr. Andrew Knutsen in image processing, data analysis, and manuscript preparation of this imaging study.

References

- Gallagher SA, Hackett PH (2004) High-altitude illness. Emergency medicine clinics of North America 22: 329-355, viii Doi 10.1016/j.emc.2004.02.001

- Hackett PH, Roach RC (2001) High-altitude illness. N Engl J Med 345: 107-114 Doi 10.1056/NEJM200107123450206

- Marmura MJ, Hernandez PB (2015) High-altitude headache. Current pain and headache reports 19: 483 Doi 10.1007/s11916-015-0483-2

- Tellez HF, Mairesse O, Macdonald-Nethercott E, Neyt X, Meeusen R, Pattyn N (2014) Sleep-related periodic breathing does not acclimatize to chronic hypobaric hypoxia: a 1-year study at high altitude in Antarctica. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine 190: 114-116 Doi 10.1164/rccm.201403-0598LE

- Weil JV (2004) Sleep at high altitude. High altitude medicine & biology 5: 180-189 Doi 10.1089/1527029041352162

- Wilson MH, Davagnanam I, Holland G, Dattani RS, Tamm A, Hirani SP, Kolfschoten N, Strycharczuk L, Green C, Thornton JSet al (2013) Cerebral venous system and anatomical predisposition to high-altitude headache. Ann Neurol 73: 381-389 Doi 10.1002/ana.23796

- Cramer NP, Korotcov A, Bosomtwi A, Xu X, Holman DR, Whiting K, Jones S, Hoy A, Dardzinski BJ, Galdzicki Z (2019) Neuronal and vascular deficits following chronic adaptation to high altitude. Experimental Neurology 311: 293-304 Doi 10.1016/j.expneurol.2018.10.007

- Kamaraj DC, Dicianno BE, Cooper RA, Hunter J, Tang JL (2013) Acute mountain sickness in athletes with neurological impairments. J Rehabil Res Dev 50: 253-262 Doi 10.1682/jrrd.2012.03.0042

- Li AY, Durbin JR, Hannah TC, Ali M, Spiera Z, Marayati NF, Dreher N, Schupper AJ, Kuohn L, Gometz Aet al (2022) High altitude modulates concussion incidence, severity, and recovery in young athletes. Brain Inj: 1-7 Doi 10.1080/02699052.2022.2035435

- Yang Y, Peng Y, He S, Wu J, Xie Q, Ma Y (2022) The Clinical Differences of Patients With Traumatic Brain Injury in Plateau and Plain Areas. Front Neurol 13: 848944 Doi 10.3389/fneur.2022.848944

- Myer GD, Smith D, Barber Foss KD, Dicesare CA, Kiefer AW, Kushner AM, Thomas SM, Sucharew H, Khoury JC (2014) Rates of concussion are lower in National Football League games played at higher altitudes. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 44: 164-172 Doi 10.2519/jospt.2014.5298

- Smith DW, Myer GD, Currie DW, Comstock RD, Clark JF, Bailes JE (2013) Altitude Modulates Concussion Incidence: Implications for Optimizing Brain Compliance to Prevent Brain Injury in Athletes. Orthop J Sports Med 1: 2325967113511588 Doi 10.1177/232596711351158

- Avants, B. B. et al. (2011) ‘A reproducible evaluation of ANTs similarity metric performance in brain image registration’, NeuroImage. Elsevier Inc., 54(3), pp. 2033–2044. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.09.025.

Figures