1654

Deep Learning Segmentation of Lung Parenchyma For UTE Proton MRI1Department of Biomedical Engineering, University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB, Canada, 2Division of Cardiology, University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB, Canada, 3Department of Radiology and Diagnostic Imaging, University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB, Canada

Synopsis

Keywords: Machine Learning/Artificial Intelligence, Lung

Accurate segmentation is required to perform quantitative analysis on lung parenchyma in ultrashort echo time (UTE) proton MRI. Deep learning methods offer a solution to this problem, however, previous application to UTE lung MRI is limited. A deep learning model was trained to segment lung parenchyma using fine tuned region growing masks as a reference. To test the generalizability of the model the performance of three different 3D UTE k-space trajectories were compared. Overall, the model produced high quality segmentation for the different acquisition approaches with improvements over training data in areas of high vessel density and high signal intensity.Introduction

Ultrashort echo time (UTE) proton MRI has seen increasing application in structural and quantitative lung imaging.1,2 To perform quantitative analysis of lung parenchyma, accurate segmentation including removal the pulmonary vessels is required. Few studies have presented lung segmentation of UTE proton images and none with consideration of blood vessel removal or pulse sequence dependence on segmentation perfomance.3 The goal of this study was to train and validate deep learning to segment lung parenchyma for modern UTE proton imaging methods with consideration of the generalizability of the method for different UTE k-space trajectories.Methods

Deep Learning Model – Given its demonstrated ability to produce high fidelity results from small training datasets, the self configuring convolutional neural network, nnU-Net4, was selected for lung parenchyma segmentation.Training Data – Training data consisted of 34 three-dimensional (3D) image datasets acquired using a free-breathing Yarnall k-space trajectory2, each with 20 respiratory phases making for an effective sample size of 680 3D volumes. To promote the sensitivity of the model to pathology, the training dataset included healthy controls (N=11) and COVID-recovered individuals (N=23), the latter of which presented with regions of signal dropout and high signal intensity (patchy consolidations). Segmentation training data was calculated using a custom region growing algorithm (RGA) in which parameters were fine tuned for each subject and visually optimized.

Model Evaluation – 64 healthy controls were used for validation of the model. Each subject was imaged at end-expiration using three UTE sequences (Fig.1): Yarnball2, Spiral VIBE5 (Siemens), and a novel Cartesian UTE sequence (CUTE). Model performance was evaluated visually, using dice similarity coefficient (DSC), and comparison of model and RGA mask volumes.

Pulse Sequence Parameters (3T PRISMA, Siemens, Erlangen, Germany) – CUTE: 400x500x300mm FOV, TE=140ms, TR=1.7ms, GRAPPA=2, 128x160x64matrix (3.125x3.125x5mm, reconstructed 2.08mm isotropic), 2° flip, 13 seconds acquisition (breath-hold). Spiral VIBE: 550x550x336mm FOV, TE=50 ms, TR=2.46 ms, 192x192x96 (2.86x2.86x3.5mm reconstructed to 1.43x1.43x3.5mm) 10 seconds acquisition (breath-hold). Yarnball: 2738 arms, 350 mm FOV, 2.0mm isotropic reconstructed, TE=100ms, TR = 2.7ms, 2° flip, 82 seconds acquisition time (free-breathing).

Results

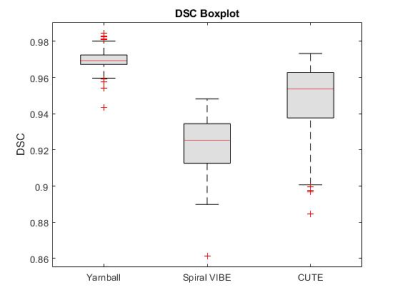

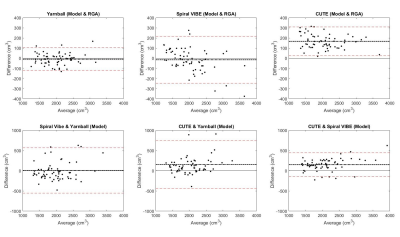

On visual inspection, nnU-Net segmentation was superior to RGA in regions of high signal intensity and increased vessel density, particularly in the higher signal intensity posterior lung, where the RGA approach tended to exclude too much parenchyma (Fig.2). The model segmentation successfully removed vessels while retaining patchy signal increases and signal dropouts in COVID-recovered individuals (Fig.3).From validation studies, Dice scores (Fig.4) for the three sequences tested were (mean ± std): 0.97 ± 0.01 (Yarnball), 0.92 ± 0.02 (Spiral VIBE), and 0.95 ± 0.02 (CUTE). Comparing the nnU-Net and RGA mask volumes (Fig.5, top row) showed the tightest spread for the Yarnball dataset, and larger but still relatively narrow confidence intervals for Spiral VIBE and CUTE datasets. Comparing model mask volumes between UTE sequences (i.e. from different acquisitions), wider confidence intervals reflect the differences in end-expiration volume between breath-hold imaging (Spiral VIBE and CUTE) and free-breathing (Yarnball).

Discussion

On visual examination nnU-Net produced high quality segmentation with similar performance to the more manual and interactive RGA approach, and with superior performance in the posterior lung where RGA had some failure in regions of increased vessel density and water density in the parenchyma.Training was performed only on the Yarnball datasets however the mean DSC for the yarnball and CUTE acquisitions were excellent (>0.95) and good for Spiral VIBE (0.92). Individual cases with lower DSC values typically had minor image artifacts or lower signal to noise. Cases of large differences in segmented volumes between RGA and model predictions were due in large to incomplete segmentation of posterior lung and other high signal regions that were missed by the reference RGA approach. Finally, discrepancies between segmented volumes for the three sequences were due to true differences in lung volumes (i.e. free-breathing and breath-hold respiratory position) and in rare cases, due to segmentation errors from severe image artifacts.

Conclusions

Overall, the segmentation masks produced by nnU-Net on images acquired with the same sequence as its training set were of extremely high quality and in some cases better than their RGA counterparts on visual inspection. The trained model was able to generalize well to images acquired using other UTE sequences that it wasn’t trained on, with errors due largely to occasional artifacts and insufficient SNR.Acknowledgements

No acknowledgement found.References

1. Voskrebenzev A, Vogel-Claussen J. Proton MRI of the Lung: How to Tame Scarce Protons and Fast Signal Decay. Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging. 2021;53(5):1344-1357.

2. Meadus WQ, Stobbe RW, Grenier JG, Beaulieu C, Thompson RB. Quantification of lung water density with UTE Yarnball MRI. Magnetic Resonance in Med. 2021;86(3):1330-1344.

3. Astley JR, Wild JM, Tahir BA. Deep learning in structural and functional lung image analysis. BJR. 2022;95(1132):20201107.

4. Fabian I, Jaeger PF, A KSA, Petersen J, Maier-Hein KH. nnU-Net: a self-configuring method for deep learning-based biomedical image segmentation. Nature Methods. 2021;18(2):203-211.

5. Olthof SC, Reinert C, Nikolaou K, et al. Detection of lung lesions in breath-hold VIBE and free-breathing Spiral VIBE MRI compared to CT. Insights into Imaging. 2021;12(1):175.

Figures