1645

Improving Kidney Volume Measurement Reproducibility in ADPKD by Averaging Measurements on Multiple Sequences1Radiology, Weill Cornell Medicine, New York, NY, United States, 2Rogosin Institute, New York, NY, United States, 3Radiology, Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons, New York, NY, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Kidney, Kidney, MRI, ADPKD

Organ volume measurements on MRI are typically performed on a single pulse sequence because of the tedious process of manual contouring. Here we use deep learning to automate kidney segmentations so that kidney volume can be measured on five abdominal MRI sequences. In 17 subjects scanned twice within 3 weeks (when no change in kidney volume was expected), the power of averaging 5 measurements improved reproducibility, achieving 2.5% absolute percent difference compared to 5.9% with manual contouring (p<0.05). Absolute percent error was reduced further to 2.1%, p<0.05 compared to manual segmentations, by excluding outlier measurements.

Introduction

Height-adjusted total kidney volume (ht-TKV) is an imaging biomarker for predicting renal function decline in patients with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD). However, ADPKD annual kidney growth rate is about 5%.1 Since this is similar to volume measurement reproducibility, patients have to wait a year or more to detect meaningful changes. This study aims to improve TKV measurements by extending AI to automatically contour kidney volumes on SSFP, T1, and T2 sequences on axial and coronal planes so that measurements on multiple sequences can be averaged.Methods

A deep-learning kidney segmentation model for axial T2 images was extended using existing images from 397 patients (356 with ADPKD and 41 without ADPKD) to the T1 and SSFP sequences on the axial and coronal planes and used to measure TKV for 17 ADPKD patients who had abdominal MRIs performed twice within 3 weeks.2 Five observers measured the kidney volumes independently by manually contouring both studies for each patient on axial T2 and with model assistance on the T1, SSFP, and T2 sequences on the axial plane and T1 and SSFP sequences on the coronal plane with a one-week gap to prevent bias. Reproducibility of kidney volume measurements was assessed to compare a) manual vs. model-assisted segmentations on the axial T2 sequence, b) model-assisted segmentations for the two exams across the 5 MRI pulse sequences, c) average of the model-assisted segmentation for the successive exams and d) average after excluding a measurement with the highest deviation from the mean.Results

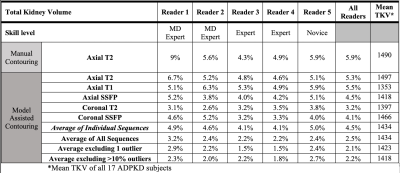

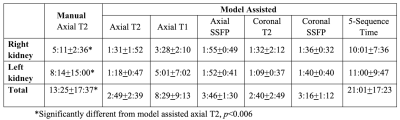

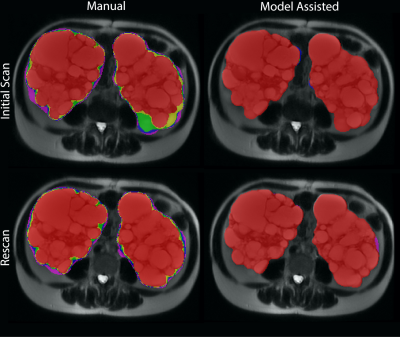

Average absolute percent difference among the individual sequences for the five observers was 4.5%, with a minimum of 3.2% on the coronal T2-weighted sequence and a maximum of 5.5% on the axial T1-weighted sequence, Table 1. Manual contouring on the axial T2 sequence, however, had an error of 5.9%. Averaging the volumes across the 5 MRI pulse sequences from the 5 observers decreased the absolute percent difference to 2.5%, p<0.05. Excluding outliers further improved reproducibility, in which the difference reduced to 2.1% after removing the TKV measurement farthest from the mean and averaging the remaining four sequences.Manual contouring on the axial T2 alone required 13:25 minutes, which decreased to 2:49 minutes (p<0.001), when using model assistance (Table 2). The axial T1 images required substantially more time to correct compared to the other sequences, 8:29 minutes, because axial T1 had twice as many slices and generally the lowest DSC compared to all the other sequences (Fig. 1). The total mean time for segmenting the kidneys on the five MRI pulse sequences using model assistance was 21:01 minutes for the five observers.

Conclusions

Accelerating kidney segmentations by extending a deep learning model, initially developed for axial T2 images, to T1 and SSFP sequences acquired in coronal and axial planes, improves reproducibility of organ volume measurement from multiple sequences of an abdominal MRI exam. In ADPKD patients imaged twice within a relatively brief interval, kidney volume measurement variability decreased significantly after averaging measurements obtained from five sequences. Variability decreased further after excluding the measurement with greatest deviation from the mean prior to averaging the remaining four volume measurements.T2-weighted images were biased toward larger volumes while axial T1 was biased toward smaller volumes. There might have been closer agreement if the T1 measurements were performed after contrast administration, but this was beyond the scope of the current study in which all subjects were imaged without contrast.3 SSFP, based upon T2/T1 contrast, produced volume measurements that closely matched the average of all five sequences. This suggests that any patient being followed with a TKV measurement algorithm utilizing only one sequence should use the same pulse sequence for every follow-up measurement. Since the SSFP sequence produced measurements closest to the average of all sequences and is an efficient acquisition that produces higher resolution data in less time, it might be considered favorable for single sequence measurements if resources are limited. However, SSFP had more artifacts, especially in large field-of-view acquisitions required to cover enlarged kidneys, potentially reducing reproducibility and confidence.4

Even though correcting the 2D U-net model required 21 minutes of radiologist time, this model can be improved to reduce the correction time. With more data, a 3D model may become practical, improving accuracy by incorporating an additional spatial dimension into discriminating kidney from background voxels.

This study demonstrates the utility of measuring organ volumes on multiple MRI pulse sequences to leverage the power of averaging for improving measurement reproducibility. Better reproducibility may provide more accurate and timely information for patients, including responses to established (e.g., tolvaptan) and investigational therapeutic interventions.5,6

Acknowledgements

No acknowledgement found.References

1. Grantham JJ, Torres VE, Chapman AB, et al. Volume Progression in Polycystic Kidney Disease. New England Journal of Medicine 2006;354(20):2122-2130.

2. Goel A, Shih G, Riyahi S, et al. Deployed Deep Learning Kidney Segmentation for Polycystic Kidney Disease MRI. Radiol Artif Intell 2022;4(2):e210205.

3. Bae KT, Tao C, Zhu F, et al. MRI-based kidney volume measurements in ADPKD: reliability and effect of gadolinium enhancement. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2009;4(4):719-725.

4. Chapman AB, Guay-Woodford LM, Grantham JJ, et al. Renal structure in early autosomal-dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD): The Consortium for Radiologic Imaging Studies of Polycystic Kidney Disease (CRISP) cohort. Kidney Int 2003;64(3):1035-1045.

5. Torres VE, Chapman AB, Devuyst O, et al. Tolvaptan in Later-Stage Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease. New England Journal of Medicine 2017;377(20):1930-1942.

6. Rangan GK, Wong ATY, Munt A, et al. Prescribed Water Intake in Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease. NEJM Evidence 2022;1(1).

Figures

Table 1. Absolute percent difference between TKV measurements on two consecutive MRI scans for each MRI pulse sequence, the average of all 5 sequences, and averages after excluding 1 outlier with the volume measurement having greatest difference from the mean or after excluding all outliers > 10% different from the mean.

Table 2. Average segmentation times (minutes:seconds).

Figure 1. Variability of the masks by scan and labeling method between five observers. The color indicates agreement as follows: Red – Five observers agree; Yellow – Four observers agree; Green – Three observers agree; Blue – two observers agree; Purple – One observer labeled these voxels (no agreement). A) First scan, manual labeling (top left). B) First scan, model assisted labeling (top right). C) Second scan, manual labeling (bottom left). D) Second scan, model assisted labeling (bottom right).