1598

Bringing MRI to Low- and Middle- Income Countries: Directions, Challenges and Potential Solutions1School of Biomedical engineering and imaging sciences, King's College London, London, United Kingdom, 2School of Medicine, Imperial College London, London, United Kingdom, 3School of Medicine, University College London, London, United Kingdom, 4Department of Radiology, Imperial College Healthcare Trust, London, United Kingdom, 5Department of Biomedical Engineering, Mbara University of Science and Technology, Mbara, Uganda, 6Royal Berkshire NHS Foundation Trust, Reading, United Kingdom, 7Department of Biomedical Engineering, Rochester Institute of Technology, New York, NY, United States, 8Department of Medicine, University of Cape Town and Groote Schuur Hospital, Cape Town, South Africa, 9Department of Cardiology, Essex Cardiothoracic Centre, Chelmsford, United Kingdom, 10Montreal Neurological Institute, McGill University, Montreal, QC, Canada, 11Berlin Ultrahigh Field Facility, Berlin, Germany

Synopsis

Keywords: Low-Field MRI, MR Value, Accessible MRI; Affordable MRI; Sustainable MRI

While innovations in MRI technology continue to advance healthcare in the global north, there is a persistent disparity in MRI access and research opportunities in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). Reasons for this longstanding disparity include technological, economic, geopolitical, and social factors. As awareness of the situation expands, concerted efforts are underway to address it by developing sustainable approaches designed with and for local communities. Here, we provide a framework of such approaches by tackling different aspects of MRI development and access in LMICs.Introduction

MRI is a mainstay of diagnostic imaging and evaluation of various clinical conditions(1-9). Despite this essential role, it is estimated that 66% of the world lacks access to MRI(10-12). As low and middle-income countries (LMICs) undergo the 'epidemiological transition' from communicable to non-communicable disease(13-16), access to MRI is becoming a pressing issue with significant health consequences. It is estimated that scaling up diagnostic imaging could prevent 2.46 million cancer-related deaths worldwide(17,18). Despite its potential in LMICs, MRI remains a technically challenging modality, requiring significant investment and trained personnel. These barriers are compounded by lack of public investment, adequate infrastructure, and reliable energy supply(11). In this work, we propose some possible solutions for developing accessible MRI with a focus on bringing MRI to LIMCs.Methods

In order to develop this comprehensive solutions framework, we reviewed existing literature on the development of affordable MRI. In addition to evaluating the literature that focused on local hardware/software challenges, we also explored how other less-reported factors, such as local macro/microeconomic policies could impact its implementation. Literature searches were performed on Medline, Embase, and the Cochrane Library electronic databases for articles published in English from inception until 1 Nov 2022. The following search terms were used (including synonyms and related words): "affordable magnetic resonance imaging", "low field MRI", "rapid MRI", "MRI local production", "cost-effective MRI". The Boolean operators AND/OR/NOT were used together with the MeSH/keywords above. Truncations/wildcards and symbols (*/?) were employed to ensure coverage of all the variations of related keywords.Results

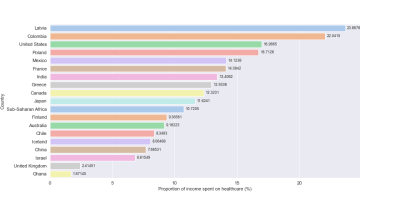

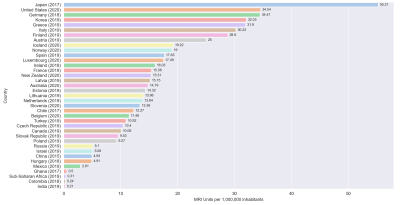

The MRI density in LMICs is significantly lower than in high-income countries (HICs), with 1.1 MRI units per million population (pmp) in LMICs compared to 26.5 MRI pmp in HICs(19,20), as outlined in Figure 1. The scanner magnetic field strength correlates with a country's income group, with HICs having significant proportion of high field scanners (B0 ≥ 3T) compared to LMICs(10,21). Alongside inter-country disparity is intra-country disparity, with a higher density of MRI scanners seen in urbanised regions than in rural communities (10,22-24). From the macroeconomic perspective, LMICs tended to allocate a lower proportion of their budget towards healthcare, spending 5.41% of GDP compared to 12.46% in HICs(12). In tandem, these factors have made MRI out of reach of millions of people despite MRI’s positive impact on quality-adjusted life years (QALYs)(25,26). 40% of healthcare spending in LMICs is still out-of-pocket(27,28). Figure 2 shows the average individual healthcare expenditure as a percentage of income. MRI scanners have specific infrastructure requirements, such as state-of-the-art hardware/software, uninterrupted power supply, cryogenic liquids, imaging suites and safety zones, which are major challenges in LMICs(22). For example, only 8 out 54 African countries are serviced by a major provider of cryogenic liquids(29). Lack of adaptation of new technology to local environment is responsible for 14-19% of donated medical equipment becoming out of service(22,30,31). Social issues such as scarcity of radiology/clinical scientists training programmes, preclude many from maximising the value of MRI. On a patient level, healthcare illiteracy is also an issue. For many patients, visiting a physician is a source of anxiety. Some might prefer alternative remedies due to distrust in modern healthcare(32). Here, initiatives like the Consortium for Advancement of MRI Education & Research in Africa (CAMERA) - a network of African experts, global partners, and ISMRM/ESMRMB – will be instrumental in implementing novel strategies to advance MRI access and research in Africa and to develop targeted training programs for healthcare providers and the public(33).Discussion

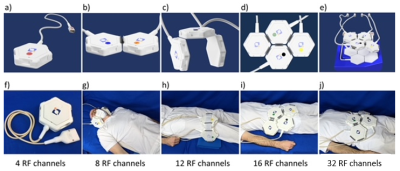

We have developed a solutions framework for increasing MRI access in LMICs. The multi-factorial approach outlines a series of steps that, undertaken together, could significantly improve MRI access in areas that are missing out on all MRI technology has to offer. The backbone of the accessibility framework is based on the adaptation of technological aspects of MRI to improve accessibility. The ideal scanner should be suitable for imaging different body parts without excessive expenditure but with accessible and made-to-last components. All these with minor/modest compromises on image quality and spatial resolution. Various components of MRI have to be evaluated such that some non-essential components could be stripped back without losing image quality. For instance, our development demonstrates that a modular and flexible multi-purpose RF array configuration bodes very well by substituting an arsenal of traditional dedicated RF coils (Figure 3). Owing to its adaptable design and multi-purpose nature the approach supports MRI of the carotids, temporomandibular joints, musculoskeletal system, heart, liver, spine, abdomen and the brain etc. Deep learning-based reconstruction algorithms could also benefit (ultra) low-field MRI due to their enhanced immunity to noise and the reduction of reconstruction artifacts(34,35). AI could help lower the technical specifications for gradient linearity and magnetic field uniformity, promoting further cost reductions for MRI hardware. Finally, portable MRI can reach rural individuals and allow for earlier diagnosis of patients who cannot access conventional MRI facilities or are mistrustful of modern technologies.Conclusion

MRI has the potential to become widely available in LMICs. With the rapid expansion of the technology, it will not be long before feasible solutions become widely available.There is a need to emphasise community engagement and co-creation to adapt the MRI machinery to local needs and make it more sustainable.Acknowledgements

No acknowledgement found.References

1. Zhang Y, Yu J. The role of MRI in the diagnosis and treatment of gastric cancer. Diagn Interv Radiol. May 2020;26(3):176-182. doi:10.5152/dir.2019.19375

2. Stusińska M, Szabo-Moskal J, Bobek-Billewicz B. Diagnostic value of dynamic and morphologic breast MRI analysis in the diagnosis of breast cancer. Pol J Radiol. 2014;79:99-107. doi:10.12659/pjr.889918

3. Bi Q, Bi G, Wang J, et al. Diagnostic Accuracy of MRI for Detecting Cervical Invasion in Patients with Endometrial Carcinoma: A Meta-Analysis. J Cancer. 2021;12(3):754-764. doi:10.7150/jca.52797

4. Alabousi M, McInnes MD, Salameh JP, et al. MRI vs. CT for the Detection of Liver Metastases in Patients With Pancreatic Carcinoma: A Comparative Diagnostic Test Accuracy Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Magn Reson Imaging. Jan 2021;53(1):38-48. doi:10.1002/jmri.27056

5. Schmidt GP, Reiser MF, Baur-Melnyk A. Whole-body MRI for the staging and follow-up of patients with metastasis. Eur J Radiol. Jun 2009;70(3):393-400. doi:10.1016/j.ejrad.2009.03.045

6. Samet JD. Pediatric Sports Injuries. Clin Sports Med. Oct 2021;40(4):781-799. doi:10.1016/j.csm.2021.05.012

7. Jacobson JA. Musculoskeletal ultrasound and MRI: which do I choose? Semin Musculoskelet Radiol. Jun 2005;9(2):135-49. doi:10.1055/s-2005-872339

8. von Knobelsdorff-Brenkenhoff F, Pilz G, Schulz-Menger J. Representation of cardiovascular magnetic resonance in the AHA / ACC guidelines. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. Sep 25 2017;19(1):70. doi:10.1186/s12968-017-0385-z

9. von Knobelsdorff-Brenkenhoff F, Schulz-Menger J. Role of cardiovascular magnetic resonance in the guidelines of the European Society of Cardiology. Journal of Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance. 2016/01/22 2016;18(1):6. doi:10.1186/s12968-016-0225-6

10. World Health O. Global atlas of medical devices. WHO Medical device technical series. World Health Organization; 2017.

11. Geethanath S, Vaughan Jr. JT. Accessible magnetic resonance imaging: A review. Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging. 2019;49(7):e65-e77. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/jmri.26638

12. World Health O. Current health expenditure (% of GDP). Accessed 27th January, 2022. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.XPD.CHEX.GD.ZS

13. Omran AR. The epidemiologic transition: a theory of the epidemiology of population change. 1971. Milbank Q. 2005;83(4):731-757. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0009.2005.00398.x

14. Boutayeb A. The double burden of communicable and non-communicable diseases in developing countries. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. Mar 2006;100(3):191-9. doi:10.1016/j.trstmh.2005.07.021

15. Mendenhall E, Kohrt BA, Norris SA, Ndetei D, Prabhakaran D. Non-communicable disease syndemics: poverty, depression, and diabetes among low-income populations. Lancet. Mar 4 2017;389(10072):951-963. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(17)30402-6

16. Temu F, Leonhardt M, Carter J, Thiam S. Integration of non-communicable diseases in health care: tackling the double burden of disease in African settings. Pan Afr Med J. 2014;18:202. doi:10.11604/pamj.2014.18.202.4086

17. Hricak H, Abdel-Wahab M, Atun R, et al. Medical imaging and nuclear medicine: a Lancet Oncology Commission. The Lancet Oncology. 2021/04/01/ 2021;22(4):e136-e172. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30751-8

18. Kuhl CK, Schrading S, Strobel K, Schild HH, Hilgers RD, Bieling HB. Abbreviated breast magnetic resonance imaging (MRI): first postcontrast subtracted images and maximum-intensity projection-a novel approach to breast cancer screening with MRI. J Clin Oncol. Aug 1 2014;32(22):2304-10. doi:10.1200/jco.2013.52.5386

19. Campus IAEAHH. IMAGINE - MRI Units (per 1 mil). Accessed 7th February, 2022. https://humanhealth.iaea.org/HHW/DBStatistics/IMAGINEMaps3.html

20. OECD. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) units (indicator). 2022. Accessed 11th February 2022.

21. Ogbole GI, Adeyomoye AO, Badu-Peprah A, Mensah Y, Nzeh DA. Survey of magnetic resonance imaging availability in West Africa. The Pan African medical journal. 2018;30:240-240. doi:10.11604/pamj.2018.30.240.14000

22. Mollura DJ, Culp MP, Lungren MP. Radiology in Global Health Strategies, Implementation, and Applications. 2nd 2019. ed. Springer International Publishing; 2019.

23. Ayasrah M. Current status, utilization, and geographic distribution of MRI devices in Jordan. Applied Nanoscience. 2021/06/14 2021;doi:10.1007/s13204-021-01904-6

24. Burdorf BT. Comparing magnetic resonance imaging and computed tomography machine accessibility among urban and rural county hospitals. J Public Health Res. Aug 13 2021;11(1)doi:10.4081/jphr.2021.2527

25. de Rooij M, Crienen S, Witjes JA, Barentsz JO, Rovers MM, Grutters JP. Cost-effectiveness of magnetic resonance (MR) imaging and MR-guided targeted biopsy versus systematic transrectal ultrasound-guided biopsy in diagnosing prostate cancer: a modelling study from a health care perspective. Eur Urol. Sep 2014;66(3):430-6. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2013.12.012

26. Gyftopoulos S, Guja KE, Subhas N, Virk MS, Gold HT. Cost-effectiveness of magnetic resonance imaging versus ultrasound for the detection of symptomatic full-thickness supraspinatus tendon tears. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. Dec 2017;26(12):2067-2077. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2017.07.012

27. World Health O. Global Spending on Health: A World in Transition 2019. Accessed 3rd February 2022.

28. World Bank: People spend half a trillion dollars out of pocket on health in developing countries annually 2019. Accessed 18th February 2022. https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2019/06/27/world-bank-people-spend-half-a-trillion-dollars-out-of-pocket-on-health-in-developing-countries-annually#:~:text=TOKYO%2C%20Japan%2C%20June%2027%2C,ahead%20of%20the%20G20%20Summit.

29. Linde. South America. Accessed 5th November, 2022. https://www.linde.com/global-locations#south-america

30. Frija G, Blažić I, Frush DP, et al. How to improve access to medical imaging in low- and middle-income countries ? EClinicalMedicine. 2021/08/01/ 2021;38:101034. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.101034

31. DeStigter K, Horton S, Atalabi OM, et al. Equipment in the global radiology environment: why we fail, how we could succeed. Journal of Global Radiology. 2019;5(1):3.

32. Bhattacharya Chakravarty A, Rangan S, Dholakia Y, et al. Such a long journey: What health seeking pathways of patients with drug resistant tuberculosis in Mumbai tell us. PLOS ONE. 2019;14(1):e0209924. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0209924

33. Anazodo UC, Ng JJ, Ehiogu B, et al. A Framework for Advancing Sustainable MRI Access in Africa. NMR Biomed. Oct 19 2022:e4846. doi:10.1002/nbm.4846

34. Wu D, Kim K, Li Q. Digital Breast Tomosynthesis Reconstruction with Deep Neural Network for Improved Contrast and In-Depth Resolution. 2020 IEEE 17th International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging (ISBI). 2020:656-659.

35. Singh R, Wu W, Wang G, Kalra MK. Artificial intelligence in image reconstruction: The change is here. Physica Medica. 2020/11/01/ 2020;79:113-125. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejmp.2020.11.012

36. OECD. Health spending (indicator). Accessed 18th March, 2022. https://data.oecd.org/healthres/health-spending.htm

37. WorldData.info. Average Income around the world. Accessed 18th March, 2022. https://www.worlddata.info/average-income.php

38. Qin C, Murali S, Lee E, et al. Sustainable low-field cardiovascular magnetic resonance in changing healthcare systems. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. Feb 14 2022;doi:10.1093/ehjci/jeab286

Figures