1585

3D Balanced Steady-State Free Precession (bSSFP) Imaging on an Ultra-Low-Field 0.055T MRI System1Laboratory of Biomedical Imaging and Signal Processing, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, China, 2Department of Electrical and Electronic Engineering, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, China

Synopsis

Keywords: Low-Field MRI, Body

Recently, there has been an impetus to develop ultra-low-field (ULF) MRI technologies, which present opportunities for low-cost and portable imaging in point-of-care scenarios. Balanced steady-state free precession (bSSFP) is a time-efficient imaging sequence yet its feasibility at ULF remains unexplored. In this study, we implemented bSSFP sequence at 0.055T, and successfully demonstrated phantom, brain and extremity imaging.Introduction

Recently, there has been an impetus to develop ultra-low-field (ULF) MRI technologies, which present opportunities for low-cost and portable imaging in point-of-care scenarios or/and low- and mid-income countries 1-5. Due to balanced gradients along all axes in each TR and phase-cycled radio frequency (RF) pulse, balanced steady-state free precession (bSSFP) intrinsically provides a high SNR and unique T2/T1 tissue contrast. Moreover, bSSFP possesses a high acquisition efficiency because of the short TR being used 6-7, which is highly relevant to ULF MRI because of significantly decreased T1 values for various biological tissues at ULF 8. However, the feasibility of bSSFP imaging at ULF remains unexplored at present time. In this study, we implemented and optimized a 3D bSSFP sequence on a custom-made 0.055T MRI scanner and successfully demonstrated phantom, brain and extremity imaging.Theory and Method

All experiments were conducted on a permanent magnet 0.055T MRI scanner 8. This scanner was based on a SmCo permanent magnet with peak-to-peak B0 inhomogeneity under 200 ppm within 24 cm DSV. It was free from any RF shielding via active EMI sensing and deep-learning driven EMI prediction and cancellation.Sequence

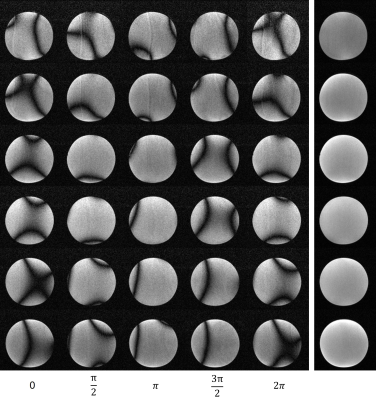

A 3D bSSFP sequence was implemented and optimized. RF excitation phase cycling was used in all scans to eliminate the banding artifacts. The number of phase cycles was adjusted based on the field inhomogeneity distribution, the position of the banding artifacts, and the SNR condition. To minimize the effects of gradient eddy currents (especially the short-term components), gradient ramp time and phase encoding gradient lobe duration and were tuned. Sampling window delay was also adjusted to suppress image artifacts.

Phantom and in vivo experiments

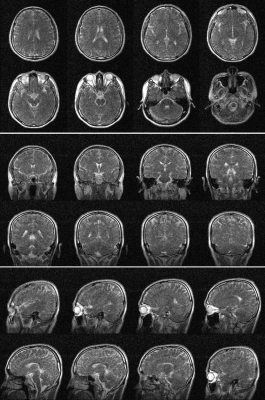

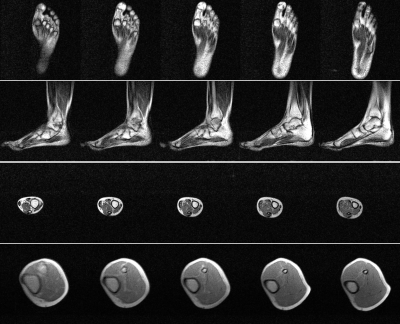

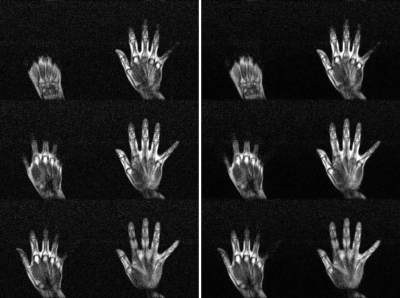

3D bSSFP sequence parameters were TR/TE = 8.8/4.4 ms, excitation flip angle (FA) = 70°, bandwidth = 33.3 kHz, matrix size = 108×108×28, field-of-view (FOV) = 216×216×140 mm3, NEX = 16, total acquisition time = 7 mins. A sinc RF pulse with 0.6 ms duration and 6 kHz bandwidth was applied with an initial zero phase. But then with phase cycling increment 2π/NEX (i.e., 22.5°) for each subsequent TR. Before scanning, linear shimming was performed with typical FID spectral FWHM and FW at 10% maximum as ~ 20 Hz and ~ 100 Hz, respectively. We implemented bSSFP protocol with two sets of parameters. One was the same as the phantom protocol above (2×2×5 mm3 resolution), which was used for both brain and extremity imaging. The other offered an isotropic 2×2×2 mm3 resolution with FA = 90°, TR /TE = 6.78/3.39 ms, bandwidth = 33.3 kHz, matrix size = 96×96×70, FOV = 200×200×140 mm3, NEX = 12, total acquisition time = 9 mins. It was also used for brain imaging. Phantom and in vivo datasets were 2× zero-padded in the k-space, resulting in a resolution of 1×1×2mm3 for the human brain and extremity images, and a resolution of 1×1×1mm3 for isotropic brain images for better visualization.

Results

Phantom images are shown in Fig. 1. Individual NEX images are also shown. From each NEX, severe banding artifacts were apparent but eliminated effectively by complex averaging all individual NEX complex images. Brain images are shown in Fig. 2 and different orientations are also displayed. Fig. 3 shows the brain images with isotropic resolution and denoising images are also shown. Fig. 4 shows the extremity images acquired with 2×2×5 mm3 resolution. Fig. 5 presents the hand images and after BM4D denoising the image quality can be improved.Discussion and Conclusions

At ULF, MRI presents several opportunities due to the unique tissue NMR properties 9-12. One distinct change occurs in T1 and T2 relaxation times for various tissues. For example, T1/T2 values for gray matter and white matter were approximately 330/110 ms and 260/100 ms at 0.055 T (vs. 1300/110 ms and 830/80 ms at 3 T 9) while CSF maintains long T1 (>1500 ms) and T2 (>1000 ms). T1/T2 values for muscle were approximately 181/42 ms at 0.058 T (vs. 1412/44 ms at 3 T 13). These dramatically altered relaxation times offer opportunities to generate various tissue contrasts in new ways by revisiting many existing data acquisition protocols, including the acquisition time efficient bSSPF and EPI sequences. T1 values are shorter in general at ULF, allowing very rapid relaxation and repetitions. Furthermore, in contrast to high-field MRI, RF specific absorption rate (SAR) is also drastically lower, permitting rapid RF excitations and flexible use of various RF envelops. Compared to EPI, bSFFP protocol offers the advantage of little geometric distortion. Although ULF MRI scanners are expected to exhibit poor relative B0 inhomogeneity (in ppm) due to their low-cost nature, the absolute B0 inhomogeneity (in Hz) is still small. Thus, bSSFP banding artifacts are manageable at ULF as demonstrated in the present study. In summary, we demonstrate 3D bSSFP as a potentially valuable protocol for human in vivo imaging at ULF.Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by Hong Kong Research Grant Council (R7003-19F, HKU17112120, HKU17127121 and HKU17127022 to E.X.W. and HKU17103819, HKU17104020 and HKU17127021 to A.T.L.L.), Lam Woo Foundation, and Guangdong Key Technologies for AD Diagnostic and Treatment of Brain (2018B030336001) to E.X.W..References

[1] Yuen MM, Prabhat AM, Mazurek MH, Chavva IR, Crawford A, Cahn BA, Beekman R, Kim JA, Gobeske KT, Petersen NH, Falcone GJ, Gilmore EJ, Hwang DY, Jasne AS, Amin H, Sharma R, Matouk C, Ward A, Schindler J, Sansing L, de Havenon A, Aydin A, Wira C, Sze G, Rosen MS, Kimberly WT, Sheth KN. Portable, low-field magnetic resonance imaging enables highly accessible and dynamic bedside evaluation of ischemic stroke. Sci Adv 2022;8(16): eabm3952.

[2] He Y, He W, Tan L, Chen F, Meng F, Feng H, Xu Z. Use of 2.1 MHz MRI scanner for brain imaging and its preliminary results in stroke. J Magn Reson 2020; 319:106829.

[3] O'Reilly T, Teeuwisse WM, de Gans D, Koolstra K, Webb AG. In vivo 3D brain and extremity MRI at 50 mT using a permanent magnet Halbach array. Magn Reson Med 2021;85(1):495-505.

[4] Sheth KN, Mazurek MH, Yuen MM, Cahn BA, Shah JT, Ward A, Kim JA, Gilmore EJ, Falcone GJ, Petersen N, Gobeske KT, Kaddouh F, Hwang DY, Schindler J, Sansing L, Matouk C, Rothberg J, Sze G, Siner J, Rosen MS, Spudich S, Kimberly WT. Assessment of Brain Injury Using Portable, Low-Field Magnetic Resonance Imaging at the Bedside of Critically Ill Patients. JAMA Neurol 2020;78(1):41-47.

[5] Cooley CZ, McDaniel PC, Stockmann JP, Srinivas SA, Cauley SF, Śliwiak M, Sappo CR, Vaughn CF, Guerin B, Rosen MS, Lev MH, Wald LL. A portable scanner for magnetic resonance imaging of the brain. Nat Biomed Eng 2021;5(3):229-239.

[6] Bieri O, Scheffler K. Fundamentals of balanced steady state free precession MRI. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2013 Jul;38(1):2-11. doi: 10.1002/jmri.24163. Epub 2013 Apr 30. PMID: 23633246.

[7] Deshpande VS, Chung YC, Zhang Q, Shea SM, Li D. Reduction of transient signal oscillations in true-FISP using a linear flip angle series magnetization preparation. Magn Reson Med 2003; 49:151–157.

[8] Liu, Yilong, et al. A low-cost and shielding-free ultra-low-field brain MRI scanner [J]. Nature communications, 2021, 12(1): 1-14.

[9] Bottomley, P. A., Foster, T. H., Argersinger, R. E. & Pfeifer, L. M. A review of normal tissue hydrogen NMR relaxation times and relaxation mechanisms from 1-100 MHz: dependence on tissue type, NMR frequency, temperature, species, excision, and age. Med. Phys. 11, 425–448 (1984).

[10] Koenig, S. H., Brown, R. D. 3rd, Adams, D., Emerson, D. & Harrison, C. G. Magnetic field dependence of 1/T1 of protons in tissue. Invest Radio. 19, 76–81 (1984).

[11] Fischer, H. W., Rinck, P. A., Van Haverbeke, Y. & Muller, R. N. Nuclear relaxation of human brain gray and white matter: analysis of field dependence and implications for MRI. Magn. Reson. Med. 16, 317–334 (1990).

[12] Wansapura, J. P., Holland, S. K., Dunn, R. S. & Ball, W. S. NMR relaxation times in the human brain at 3.0 tesla. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 9, 531–538 (1999).

[13] Stanisz, G.J., Odrobina, E.E., Pun, J., Escaravage, M., Graham, S.J., Bronskill, M.J. and Henkelman, R.M. (2005), T1, T2 relaxation and magnetization transfer in tissue at 3T. Magn. Reson. Med., 54: 507-512. https://doi.org/10.1002/mrm.20605

Figures