1563

Spinal cord fMRI to investigate the Relapsing-Remitting Multiple Sclerosis (RRMS) patients1Nanotec, CNR, Roma, Italy, 2IRCSS Santa Lucia Foundation, Rome, Italy, 3IRCCS Santa Lucia Foundation, Roma, Italy, 4CREF, Roma, Italy, 5Radiation Oncology, Campus Bio-Medico University of Rome, Roma, Italy

Synopsis

Keywords: Spinal Cord, fMRI (task based), BOLD signal

We have studied Relapsing-Remitting Multiple Sclerosis (RRMS) patients group with spinal cord fMRI during a multilevel force grip motor task. We demostrated the possibility to use spinal cord fMRI as a biomarker for clinical application.Introduction

Preliminary studies of patients with spinal cord injuries (SCI) and multiple sclerosis (MS) have demonstrated an altered activity in the SC, depending on the injury severity or the advancement of the disease [1-4].In particular, MS studies have benefitted the most from advanced quantitative Spinal cord (SC) imaging techniques, spanning from cord atrophy measurements, fMRI[4], DTI [5] and also magnetization transfer ratio (MTR).

MS is a disease that is being studied quite extensively with fMRI, in both the brain and SC [6]. A key challenge that has been identified for fMRI assessments of MS is that interpretation may be affected by disease-driven differences in task performance. In order to overcome this challenge, studies have been carried out with larger populations, and use of several motor, visual and cognitive tasks in groups representing all major clinical phenotypes of the disease.

In the last decade, experiments based on the task-dependent modulation of spinal cord fMRI activations signal in response to innocuous and painful sensory stimuli or motor tasks have been performed. The resultant fMRI signal was found to increase in sites consistent with the known functional neuroatonomy of the spinal cord. Different groups observed activity changes in the cervical spinal cord during a motor task of the upper limb movements [7-12].

In this framework we have studied 54 control subjects and 35 "Relapsing-Remitting Multiple Sclerosis (RRMS) patients group" with spinal cord fMRI during a multilevel force grip motor task. We have also improved the experimental protocols and data analysis processing to improve the quality of the images.

Methods

Subjects &Patients: 54 healthy subjects and 34 MSC patients (29.5 ± 6.5 years old, mean ± standard deviation) participated in this study. All the patients undergoes under PASAT test, which is widely used to evaluate processing speed and executive function in patients with multiple sclerosis, traumatic brain injury, and other neurological disorders. All enrolled subjects and patients gave informed consent for participating in the study, which was approved by the Local Ethics Committee and was conducted in accordance with the Helsinki declaration.MRI acquisition protocol: Acquisitions were performed on a Philips Achieva 3T MR scanner (Philips Medical Systems, Best, The Netherlands) using a neurovascular coil array. T2*-weighted fMRI data were acquired using a 2D GE-EPI sequence along axial planes, with the following parameters: TE/TR = 25/3000 ms, Flip angle=80°, FOV = 140 x 140 x 143 mm3 (AP x RL x IS), acquisition matrix 92 x 94 x 34 and reconstructed to a voxel size 1.5x1.5x3 mm3. 2 saturation bands were applied (anteriorly and posteriorly to the spinal cord) and a SENSE factor of 2 was used. Anatomical reference images were acquired using 3D T1-weighted gradient echo sequence (TE/TR = 5.89/9.59 ms, flip angle = 9°, FOV = 240 x 240 x 192 mm3, resolution = 0.75 x 0.75 x 1.5 mm3 interpolated). Heartbeat and respiration data were recorded using scanner integrated plethysmograph and respiratory belt during all functional runs.

Task: Immediately before the fMRI session, subjects underwent an assessment and training phase outside the MR scanner with the Grip force response device (HHSC-1x1-GRFC-V2, CURDES, Philadelphia, US). In a first trial, the maximum sustainable voluntary contraction force (MSF) was determined. The task consisted in a block-designed isometric motor contraction performed with the right hand and guided by a visual feedback system to apply a given level of force on the grip device, pseudo randomly selected among 20%, 40% or 50% of MSF of the subject. The stimulation protocol started and ended with a rest epoch, and overall included 11 epochs, alternating task execution and rest. Epochs lasted 30 s each, for a total duration of 5.5 minutes.

The data was analysed using a developed pipeline based on Spinal Cord Toolbox [13].

Results & Discussion

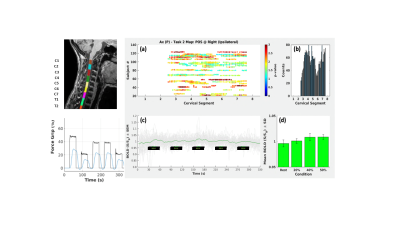

In MS patients, we found the functional activation with respect to the task more widespread among the cervical levels, particularly between C3-C5 and C7-C8, with respect to the healthy subjects, as shown in figure 1 and 2. This is a confirmation of what was found by Stroman et al. [14] through the use of thermal stimulation: subjects with injured spinal muscles respond differently depending on the severity of the injury, thus showing a less localized activation. Even though this heterogeneity can be linked to the state of the disease, it also depends on the difficulties of the patients to maintain a stable force level, especially in the application of 20% of the MSF. This was confirmed by the second level inferential analysis (group analysis), which showed areas of scattered and non-reproducible activations among the individual patients. In addition, it was also found that in MS patients the parametric dependence of the functional response on the isometric motor task was more clearly evident than in the controls. This result is in agreement with the studies conducted by Agosta et al. [2].Conclusions

The obtained results suggest that fMRI on the spinal cord can be reliably used to study the functional effect, which precedes any clinical effect, on a population. Therefore it is possible to non-invasively analyse the results of neuro-rehabilitative or pharmacological treatments and to understand the average response on a population.Acknowledgements

No acknowledgement found.References

1. Stroman, P., et al. Spinal Cord, 2004. 42(2): p. 59-66.

2. Agosta, F., et al. Neuroimage, 2008. 39(4): p. 1542-1548.

3.Wheeler-Kingshott, C., et al. Neuroimage, 2014. 84: p. 1082-1093

4. Chen, Y., et al. Brain Sciences, 2020. 10(11), 857.5.

5. Hori M, et al. Magn Reson Med Sci. 2022 Mar 1; 21(1):58-70

6. Agosta, F., et al. Radiology, 2009. 253(1):p. 209-215.

7. Yoshizawa, T., et al. Neuroimage, 1996. 4(3): p. 174-182.

8. Stroman, P. Magnetic resonance in medicine, 1999. 42(3): p. 571-576.

9. Stroman, P. and L. Ryner. Magnetic resonance imaging, 2001. 19(1): p. 27-32.

10.Madi, S., et al. American journal of neuroradiology, 2001. 22(9): p. 1768-1774.

11. Backes, W.H., et al. American Journal of Neuroradiology, 2001. 22(10): p. 1854-1859.

12 Maieron, M., et al. The Journal of neuroscience, 2007. 27(15): p. 4182-4190

13. De Leener B, et al. NeuroImage 2018; 165: 170-179.

14. P. Stroman et al., Neuroimage, 2002. vol. 17, (4) pp. 1854-1860,