1540

Evidence of association between lower cerebral white matter myelin content and rapid cognitive decline in cognitively unimpaired individuals1Laboratory of Clinical Investigation, National Institute on Aging, Baltimore, MD, United States, 2Laboratory of Behavioral Neuroscience, National Institute on Aging, Baltimore, MD, United States, 3Translational Gerontology Branch, National Institute on Aging, Baltimore, MD, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Neurodegeneration, Aging, Myelin

Myelin plays an essential role in the normal functioning of the central nervous system. However, how myelination influences longitudinal changes in cognitive performance, especially in cognitively normal (CN) individuals, remains unclear. Using a linear mixed-effects regression analysis, we examined the association between myelin content and changes in cognitive domain scores obtained over several years prior to the time of the MRI scan. We demonstrated strong and statistically significant relationships between myelin content and the rates of change in cognitive performance in several white matter regions. These findings highlight the importance of white matter, specifically myelin integrity, in cognitive functioning.INTRODUCTION

Myelin enables the proper functioning of the human brain (1-3). Besides promoting efficient electrical impulse transmission through the facilitation of saltatory nerve conduction, growing evidence indicates that myelin may perform additional functions of fundamental importance. Therefore, any compromise to the myelin integrity can lead to functional and cognitive impairments. Indeed, studies conducted on mice have shown that myelin synthesis decreases substantially during aging, consequently contributing to the decline in cognitive function (4). These findings and evidence from human studies (5, 6) raise the possibility that altered myelin content may underlie cognitive deficits in neurodegenerative diseases, including mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease (AD). However, despite this compelling evidence of a close relationship between myelin status and cognitive performance, the effect of myelin content on changes in cognition in normative aging has not been previously evaluated. In this work, using linear mixed-effects regression analysis, we examined the association between myelin content, measured using either myelin water fraction (MWF, sensitive and specific) or longitudinal relaxation rate (R1, sensitive but nonspecific), and changes in cognitive domain scores of memory, attention, executive function and verbal fluency measured retrospectively over several years prior to the time of MRI.METHODS

ParticipantsThe study sample was limited to 123 cognitively normal participants from the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging (BLSA) and the Genetic and Epigenetic Signatures of Translational Aging Laboratory Testing (GESTALT). At each visit, cognitive domain scores were obtained for memory, attention, executive function, and verbal fluency. Detailed neuropsychological testing descriptions can be found in previous publications (7).

MRI acquisition of in vivo myelin content

All MRI scans were performed on a 3 T whole-body Philips MRI system (Achieva, Best, The Netherlands) using the internal quadrature body coil for transmission and an eight-channel phased-array head coil for signal acquisition. Under the approval of the institutional review board, all participants underwent the BMC-mcDESPOT imaging protocol. Detailed scan protocol can be found in previous publications (8-10). For each participant, a whole-brain R1 map and a whole-brain MWF map were generated and registered to the Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) template. Our regions of interest (ROIs) included the whole brain, frontal, parietal, temporal, occipital, and cerebellum of WM defined using MNI in FSL. Within each ROI, the mean MWF and R1 values were calculated.

Statistical analysis

Using separate linear mixed-effects models for each of the four cognitive domains and each of the six WM ROIs, we assessed associations between regional MWF or R1 and retrospective changes in verbal fluency, executive function, memory, or attention. The explicit regression model is given by:

$$$\text{Cog}_{ij}=\beta_0+\beta_{\text{age}}\times\text{age}_i+\beta_{\text{sex}}\times\text{sex}_i+\beta_{\text{race}}\times\text{race}_i+\beta_{\text{EDY}}\times\text{EDY}_i+\beta_{\text{time}}\times\text{time}_{ij}+\beta_{\text{MRI}}\times\text{MRI}_i+\beta_{\text{time $\times$ MRI}}\times\text{MRI}_i \times\text{time}_{ij}+\epsilon_{ij}+b_i,$$$

where $$$\text{Cog}_{ij}$$$ is the cognitive domain (i.e., verbal fluency, memory, executive function, or attention) score of subject $$$$i$$$ at time-point $$$j$$$.

RESULTS & DISCUSSION

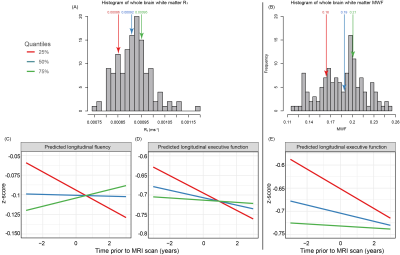

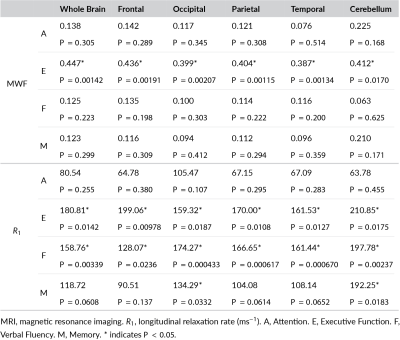

Figure 1 (A, B) shows the histogram of R1 and MWF derived from the whole brain white matter. We did not find cross-sectional associations between R1 or MWF in any ROI and cognitive domain scores to be statistically significant. However, lower R1 was associated with steeper longitudinal decline in executive function and verbal fluency, and lower MWF was associated with steeper longitudinal decline in executive function for all six ROIs (Table 1). Additionally, higher R1 levels in the occipital WM and cerebellar WM were associated with a reduced rate of decline in memory. The significant associations in the whole brain WM region as shown as an example in Figure 1 (C, D, E). Only executive function was associated with MWF out of the four cognitive domains we investigated, consistent with previous MRI observations of associations between deficits in executive function and white matter hyperintensity load (11, 12). Whereas associations with R1 additionally included verbal fluency and memory. We speculate the additional associations for R1 is partially the result of the sensitivity but non-specificity of R1 to various physiological parameters other than myelination.In light of the increasing limitations of the amyloid hypothesis, alterations in myelination have been suggested as a pathophysiologic etiology of Alzheimer's disease and, potentially, other dementias (13-15). Establishing the evidence between lower myelination and rapid cognitive decline offers new windows for therapeutic interventions for Alzheimer's disease and dementia. For the first time, our results demonstrated a direct relationship between myelin content and the rate of changes in cognition in CN individuals. According to these findings, myelin integrity may determine longitudinal cognition performance in CN individuals and may be a sensitive biomarker for predicting cognitive changes at an early stage of neurodegenerative disease.

CONCLUSIONS

In this longitudinal retrospective study, we showed that myelin content is associated with retrospective changes in cognitive performance. This work motivates further studies on the relationship between myelin deficits and cognitive impairment in neurodegenerative disease. These studies may lead to new neuroimaging biomarkers of brain microstructure as well as more rational design of therapeutic interventions.Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health.References

1. Nave KA. Myelination and the trophic support of long axons. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2010;11(4):275-83.

2. McKenzie IA, Ohayon D, Li H, de Faria JP, Emery B, Tohyama K, et al. Motor skill learning requires active central myelination. Science. 2014;346(6207):318-22.

3. de Faria O, Jr., Pivonkova H, Varga B, Timmler S, Evans KA, Karadottir RT. Periods of synchronized myelin changes shape brain function and plasticity. Nat Neurosci. 2021;24(11):1508-21.

4. Wang F, Ren SY, Chen JF, Liu K, Li RX, Li ZF, et al. Myelin degeneration and diminished myelin renewal contribute to age-related deficits in memory. Nat Neurosci. 2020;23(4):481-6.

5. Bartzokis G. Age-related myelin breakdown: a developmental model of cognitive decline and Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2004;25(1):5-18; author reply 49-62.

6. Bouhrara M, Reiter D, Bergeron C, Zukley L, Ferrucci L, Resnick S, et al. Evidence of demyelination in mild cognitive impairment and dementia using a direct and specific magnetic resonance imaging measure of myelin content. Alzheimer's & Dementia. 2018;14(8):998-1004.

7. Ziontz J, Bilgel M, Shafer AT, Moghekar A, Elkins W, Helphrey J, et al. Tau pathology in cognitively normal older adults. Alzheimers Dement (Amst). 2019;11:637-45.

8. Bouhrara M, Reiter DA, Bergeron CM, Zukley LM, Ferrucci L, Resnick SM, et al. Evidence of demyelination in mild cognitive impairment and dementia using a direct and specific magnetic resonance imaging measure of myelin content. Alzheimers Dement. 2018;14(8):998-1004.

9. Bouhrara M, Rejimon AC, Cortina LE, Khattar N, Bergeron CM, Ferrucci L, et al. Adult brain aging investigated using BMC-mcDESPOT–based myelin water fraction imaging. Neurobiology of aging. 2020;85:131-9.

10. Kiely M, Triebswetter C, Cortina LE, Gong Z, Alsameen MH, Spencer RG, et al. Insights into human cerebral white matter maturation and degeneration across the adult lifespan. NeuroImage. 2022;247:118727.

11. Brugulat-Serrat A, Salvado G, Sudre CH, Grau-Rivera O, Suarez-Calvet M, Falcon C, et al. Patterns of white matter hyperintensities associated with cognition in middle-aged cognitively healthy individuals. Brain Imaging Behav. 2020;14(5):2012-23.

12. Smith EE, Salat DH, Jeng J, McCreary CR, Fischl B, Schmahmann JD, et al. Correlations between MRI white matter lesion location and executive function and episodic memory. Neurology. 2011;76(17):1492-9.

13. Bartzokis G, Lu PH, Mintz J. Human brain myelination and amyloid beta deposition in Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2007;3(2):122-5.

14. Bartzokis G. Alzheimer's disease as homeostatic responses to age-related myelin breakdown. Neurobiol Aging. 2011;32(8):1341-71.15. Balaji S, Johnson P, Dvorak AV, Kolind SH. Update on myelin imaging in neurological syndromes. Curr Opin Neurol. 2022;35(4):467-74.

Figures