1539

Reduction of GABA in the visual cortex of glaucoma patients is linked to decreased neural specificity.

Ji Won Bang1, Carlos Parra1, Kevin Yu1, Gadi Wollstein1,2,3, Joel S Schuman1,2,3,4, and Kevin C Chan1,2,3,4,5

1Department of Ophthalmology, NYU Grossman School of Medicine, NYU Langone Health, New York University, New York, NY, United States, 2Center for Neural Science, College of Arts and Science, New York University, New York, NY, United States, 3Department of Biomedical Engineering, Tandon School of Engineering, New York University, New York, NY, United States, 4Neuroscience Institute, NYU Grossman School of Medicine, NYU Langone Health, New York University, New York, NY, United States, 5Department of Radiology, NYU Grossman School of Medicine, NYU Langone Health, New York University, New York, NY, United States

1Department of Ophthalmology, NYU Grossman School of Medicine, NYU Langone Health, New York University, New York, NY, United States, 2Center for Neural Science, College of Arts and Science, New York University, New York, NY, United States, 3Department of Biomedical Engineering, Tandon School of Engineering, New York University, New York, NY, United States, 4Neuroscience Institute, NYU Grossman School of Medicine, NYU Langone Health, New York University, New York, NY, United States, 5Department of Radiology, NYU Grossman School of Medicine, NYU Langone Health, New York University, New York, NY, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Neurodegeneration, Brain

Glaucoma is an age-related neurodegenerative disease of the visual system. Although increasing number of studies indicated its widespread involvements of the eye and the brain, very little is known about the underlying metabolic mechanisms. Thus, here we investigated the GABAergic and glutamatergic systems in the visual cortex of glaucoma patients, as well as neural specificity. Our study demonstrated that glaucoma is accompanied by the reduction of GABA and glutamate in the visual cortex. Further, the reduction of GABA but not glutamate predicted neural specificity. This suggests that GABA loss in the visual cortex degrades the neural specificity in glaucoma.Introduction

Glaucoma, an age-related neurodegenerative disease, is known to affect both the eye and the brain1,2. However, it is yet largely unknown whether glaucoma alters metabolic mechanisms in the brain and whether these changes have any functional relevance to sensory and cognitive functions. Thus, using proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy and functional magnetic resonance imaging, we examined the levels of GABA and glutamate in the visual cortex, as well as neural specificity, which is shaped by GABA and glutamate signals3.Methods

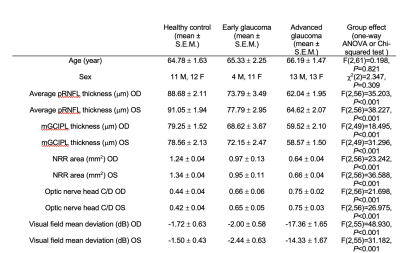

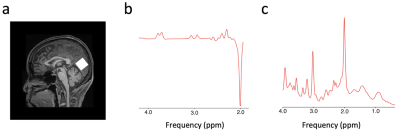

Forty-one glaucoma subjects [age= 65.88 ± 1.23 (mean ± S.E.M.); 41.5% male] and twenty-three healthy controls [age= 64.78 ± 1.63 (mean ± S.E.M.); 47.8% male] were scanned inside a 3-Tesla Siemens Prisma MRI scanner (Table 1). For anatomical localization, we obtained high-resolution T1-weighted MR images using a multi-echo magnetization-prepared rapid gradient echo sequence (voxel size=0.8 0.8 0.8 mm3). The levels of GABA and glutamate were measured from a voxel (2.2×2.2×2.2 cm3) positioned in the visual cortex using MEGA-PRESS (TR/TE= 1500/68 ms) with double-banded pulses and PRESS sequences (TR/TE= 3000/30 ms) (Figure 1). Then, we obtained functional MR images using a gradient-echo echo-planar imaging (EPI) sequence (TR/TE= 1000/32.60 ms, voxel size=2.3 2.3 2.3 mm3) while subjects were presented with a flickering checkerboard pattern at the horizontal vs. vertical meridians. In addition to MR images, we also obtained the clinical ophthalmic data using the Cirrus spectral-domain optical coherence tomography device (Zeiss, Dublin, CA, USA), and the Humphrey visual field perimetry using the Swedish Interactive Thresholding Algorithm 24-2 standard (Zeiss, Dublin, CA, USA).We fitted GABA and glutamate spectra using the LCModel software4 and normalized the levels of GABA and glutamate using total creatine. For the fMRI data, we applied motion correction, registered to the individual’s structural template, and extracted the blood-oxygenation-level-dependent (BOLD) signals from the visual cortex (hOc1-hOc4v), which spatially overlapped with the MRS voxel. Then we shifted the BOLD signals by 6 s to account for the hemodynamic delay, removed the linear trend, and normalized the BOLD signals for each voxel. To measure neural specificity, which is the dissimilarity in neural activities between horizontal and vertical visual stimuli, we calculated the Fisher z-transformed correlation coefficient of brain activity patterns between two visual representations. We also obtained the measure for retinal structural damage by extracting a common component from each individual’s peripapillary retinal nerve fiber layer (pRNFL) thickness, macular ganglion cell-inner plexiform layer (mGCIPL) thickness, optic nerve head cup-to-disc (C/D) ratio, and neuroretinal rim (NRR) area of left and right eyes in optical coherence tomography using principal component analysis.

Results

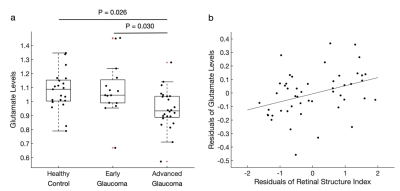

We first examined whether the GABA levels in the visual cortex change with glaucoma by conducting a one-way ANCOVA while controlling for age. The results showed that the GABA levels are significantly lower in advanced glaucoma patients compared to healthy controls (main effect of group, P=0.002; advanced glaucoma vs. healthy controls, Bonferroni P=0.001; early glaucoma vs. advanced glaucoma, Bonferroni P=0.534; Figure 2a). Then we examined whether the damages on the retina structure are associated with the loss of GABA by performing a linear regression analysis. We observed that the retina structure significantly predicted the GABA levels after adjusting age (P=0.020, partial correlation=0.339; Figure 2b).Next, we tested if similar changes appear to glutamate levels by conducting a one-way ANCOVA while controlling for age. We observed that the glutamate levels are significantly lower in advanced glaucoma patients compared to healthy controls and early glaucoma patients (main effect of group, P=0.009; advanced glaucoma vs. healthy controls, Bonferroni P=0.026, early glaucoma vs. advanced glaucoma, Bonferroni P=0.030; Figure 3a). Further, the linear regression analysis showed that the retina structure significantly predicted the glutamate levels after controlling age (Figure 3b).

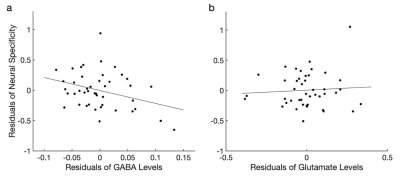

Given that GABA and glutamate levels decrease with increasing glaucoma severity, we further tested whether the neural specificity can be predicted by GABA and glutamate levels after adjusting the effects of retina structure, age and gray matter volume of the visual areas. The results demonstrated that GABA levels (P=0.037, partial correlation=0.331; Figure 4a), but not glutamate (P=0.663, partial correlation=0.071; Figure 4b) significantly predicted the neural specificity (P=0.037, partial correlation=0.339).

Discussion

Our study demonstrated that glaucoma involves reduction of GABA and glutamate levels in the visual cortex. In addition, the reduction of GABA, but not glutamate is tightly associated with neural specificity. These results suggest that glaucoma-specific loss of GABA may play a critical role in degrading the neural specificity in the visual cortex. Future studies are needed to determine whether targeting GABA could improve the neural specificity in glaucoma.Conclusion

Our study demonstrated a tight link between neural specificity and reduction of GABA in the visual cortex of glaucoma patients.Acknowledgements

This work is supported in part by the National Institutes of Health R01-EY028125, R01-EY013178, and P41-EB017183 (Bethesda, Maryland), BrightFocus Foundation G2016030, G2019103, and G2021001F (Clarksburg, Maryland), and an unrestricted grant from Research to Prevent Blindness to NYU Langone Health Department of Ophthalmology (New York, New York).References

1. Chan JW, Chan NCY, Sadun AA. Glaucoma as Neurodegeneration in the Brain. Eye Brain. 2021;13:21-8.

2. Murphy MC, Conner IP, Teng CY, Lawrence JD, Safiullah Z, Wang B, et al. Retinal Structures and Visual Cortex Activity are Impaired Prior to Clinical Vision Loss in Glaucoma. Sci Rep-Uk. 2016;6.

3. Isaacson JS, Scanziani M. How inhibition shapes cortical activity. Neuron. 2011;72(2):231-43.

4. Provencher SW. Automatic quantitation of localized in vivo 1H spectra with LCModel. NMR Biomed. 2001;14(4):260-4.

Figures

Table 1. Demographic and clinical characteristics of the glaucoma and healthy subjects. Early glaucoma was categorized as glaucoma patients with average visual field mean deviation better than -6.0dB and advanced glaucoma was determined as average visual field mean deviation worse than -6.0dB. Abbreviations: pRNFL: peripapillary retinal nerve fiber layer; mGCIPL: macular ganglion cell-inner plexiform layer; NRR: neuroretinal rim; C/D: cup-to-disc; OD: oculus dexter (right eye); OS: oculus sinister (left eye).

Figure 1. Exemplar voxel location for proton MRS and representative spectra for GABA and glutamate. a, The levels of GABA and glutamate were measured from a 2.2 x 2.2 x 2.2 cm3 voxel (white box) positioned in the occipital cortex. b, A sample GABA spectrum from the MEGA-PRESS sequence. The GABA peak is at 2.8-3.2 ppm. c, A sample glutamate spectrum from the PRESS sequence. The glutamate peak is at 2.2-2.4 ppm.

Figure 2. GABA levels in the visual cortex. a, The GABA levels (normalized to total creatine levels) were significantly lower in advanced glaucoma patients compared to healthy controls (Bonferroni-correctedP=0.001). Individual data points are overlaid on the box and whisker plots and the outlier is plotted as a red plus sign. b, The retina structure significantly predicted the GABA levels after controlling for age (r=0.339, P=0.020).

Figure 3. Glutamate levels in the visual cortex. a, The glutamate levels (normalized to total creatine levels) were significantly lower in advanced glaucoma patients compared to healthy controls (Bonferroni-correctedP=0.026) and early glaucoma patients (Bonferroni-corrected P=0.030). Individual data points are overlaid on the box and whisker plots and the outlier is plotted as a red plus sign. b, The retinal structure was positively correlated with the glutamate levels after controlling for age (r=0.364, P=0.011).

Figure 4. Neural specificity is predicted by GABA, but not glutamate. a, The GABA levels significantly predicted the neural specificity after controlling for the glutamate levels, retinal structure index, age, and the gray matter volume of the visual areas (r=-0.331, P=0.037). b, The glutamate levels were not associated with the neural specificity after adjusting the GABA levels, retinal structure index, age, and the gray matter volume of the visual areas (r=0.110, P=0.498).

DOI: https://doi.org/10.58530/2023/1539