1536

Disruptions in Functional Connectivity in Pre-manifest Huntington Disease: A Data-Driven, Whole-Brain fMRI Study1Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, United States, 2McLean Hospital, Belmont, MA, United States, 3Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, MA, United States, 4Stephens Family Clinical Research Institute, Carle Foundation Hospital, Urbana, IL, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Neurodegeneration, fMRI (resting state), Huntington disease, striatum, data-driven multi-voxel pattern analysis

Huntington disease (HD) is a progressive, autosomal dominant disease caused by a pathological expansion of CAG repeats in the HTT gene1,2. A clinical diagnosis of HD is made at the appearance of unequivocal motor signs. However, in the “premanifest” stage, due to slowly progressive neurodegenerative changes1,2, subtle motor, psychiatric and cognitive decline occurs many years prior to diagnosis3. The sequelae of neural circuit dysfunction remains unclear. Improving our mechanistic understanding of functional brain connectivity alterations prior to disease manifestation will help identify sensitive biomarkers of disease progression1,4–6. Data-driven analysis of high-quality functional magnetic resonance imaging data will guide such efforts.Introduction

Huntington disease (HD) is a progressive, autosomal dominant disease caused by a pathological expansion of CAG repeats in the HTT gene1,2. Genetic testing can reliably identify individuals who will eventually develop HD; however, HD is a slowly progressing disease with a long prodrome3 and hence there exists an urgent need for sensitive biomarkers of disease progression4-6. Proximity to clinical diagnosis is currently approximated using statistical models based upon CAG repeat length and age but these variables only account for between 50% and 69% of the variance observed in age at diagnosis7,8. Current statistical models remain too imprecise for predicting when overt symptoms will manifest at the individual level. This in turn poses a significant challenge for the design of disease modifying trials in HD as improperly timed interventions run the risk of being initiated either too early (in which case, detecting a significant clinical effect would be challenging) or too late (in which case irreversible changes may already have occurred). Defining the earliest and most reliable biomarkers of disease progression remains critically important9. This study examines the resting-state functional-connectivity (rsFC) of adults with genetically-confirmed HD who are in the premanifest stage using fMRI data acquisition and analysis techniques including high temporal resolution using simultaneous multi-slice acquisition and unbiased whole-brain connectome-wide multi-voxel pattern analysis (MVPA) for the assessment of rsFC.Methods

Participants: Genetically-confirmed HD patients in the pre-manifest stage and healthy controls (HC) - matched for age, sex, education - were recruited for fMRI sessions to assess both fMRI networks and performance on multiple cognitive and motor tasks. HD subjects underwent clinical assessment by trained movement disorder neurologists to ensure they were in the premanifest stage.Image Pre-Processing: Resting-state fMRI data from HD and matched HC were preprocessed in SPM12 with realignment with respect to the first volume and normalization to MNI space with respect to the EPI template. CONN Toolbox was used for additional preprocessing steps such as band pass filtering (0.008-0.1 Hz), physiological signal denoising to eliminate contributions of white matter and cerebrospinal fluid, and regressing out movement effects and their first-order derivatives along with motion outliers. Quality assurance (QA) was carried out by examining between group differences in head motion parameters.

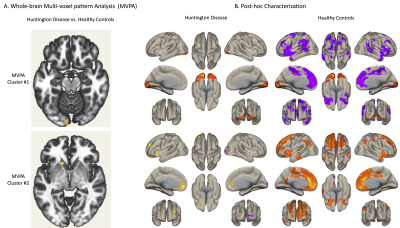

Multi-voxel Pattern Analysis (MVPA): We used the MVPA method implemented in the CONN Toolbox (https://web.conn-toolbox.org/fmri-methods/connectivity-measures/networks-voxel-level). MVPA consists of a two-level dimension reduction process. At the first level, 64 PCA components are retained from voxel-to-voxel correlation structure for each subject. A multivariate connectivity map is constructed for each seed-voxel to all other voxels of the brain. This multivariate connectivity map is derived from the seed-based correlations for each seed-voxel separately using singular value decomposition for each subject for dimensionality-reduction. The component scores of these PCA components are then used for the second level analysis, during which 3 group-MVPA components are retained from the connectivity maps. Voxel threshold of p < 0.001, and a cluster-wise-false discovery rate corrected threshold of p < 0.05 are used to determine the clusters that have altered rsFC for the F-test between the two groups (HD vs. HC) in a whole-brain connectivity analysis. The clusters generated by MVPA are then used as regions of interests (ROIs) for a seed-based-connectivity analysis for further post-hoc characterization. For the first-level seed-to-voxel analysis, Pearson’s correlation coefficients are computed between the seed time-series and time-series of the rest of the voxels in the brain volume. Whole-brain seed-to-voxel r-maps are then transformed to z-maps and voxel-wise general linear model analysis are conducted on the connectivity values at the second level for within group (HD, HC) comparisons.

Results

18 HD patients and 18 HC were recruited. Mean HD age was 37.9+/-11, years of education 15+/-2.7 and 61% females. Group differences in age, sex and education were not significant. A significant difference in mean head motion, detected during QA, was accounted for in the second level analysis. MVPA converged on two clusters: left occipital cortex and left caudate (Fig. 1A). Using these regions as seed ROIs for whole-brain seed-to-voxel analysis revealed network level abnormalities in the HD group including 1) loss of widespread negative correlations from left occipital cluster to multiple regions within the prefrontal cortex and striatum and 2) loss of positive correlations between the left caudate and bilateral prefrontal cortices (Fig. 1B).Discussion

The rsFC abnormalities we report using whole-brain, data-driven analyses support the hypothesis that brain-network changes precede clinical diagnosis of HD, and highlight two networks centered on caudate and occipital cortex. Both of these regions have previously been shown to undergo progressive atrophy as the disease approaches the manifest HD state10. Circuit dysfunction within and between these two regions may provide a functional link to the subtle, yet reliable cognitive changes in the premanifest state, including, for example, early automated visuospatial processing deficits11–13.Conclusion

Our results, coherent with existing structural, functional, and rsFC literature in HD, extend previous literature reporting striatal and occipital cortex abnormalities in the neuropathology of HD, and highlight the occipital-striatal circuitry as a potential target for diagnostic, predictive, and prognostic developments in HD. Future investigation of this circuitry in premanifest HD may reveal opportunities to detect disease progression at an earlier stage, which is critically important for disease-modifying treatment trials.Acknowledgements

This study was funded in part by the Huntington’s disease Society of America (HDSA) Human Biology project grant.References

1. Dogan I, Eickhoff CR, Fox PT, et al. Functional connectivity modeling of consistent cortico-striatal degeneration in Huntington’s disease. Neuroimage Clin. 2015;7:640-652. doi:10.1016/J.NICL.2015.02.018 2. Penney JB, Vonsattel JP, MacDonald ME, Gusella JF, Myers RH. CAG repeat number governs the development rate of pathology in huntington’s disease. Ann Neurol. 1997;41(5):689-692. doi:10.1002/ANA.410410521

3. Hart E, Middelkoop H, Jurgens CK, Witjes-Ané MNW, Roos RAC. Seven-year clinical follow-up of premanifest carriers of Huntington’s disease. PLoS Curr. Published online 2011. doi:10.1371/CURRENTS.RRN1288

4. Clinical and Biomarker Changes in Premanifest Huntington Disease Show Trial Feasibility: A Decade of the PREDICT-HD Study - PMC. Accessed October 28, 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4000999/

5. Tabrizi SJ, Reilmann R, Roos RAC, et al. Potential endpoints for clinical trials in premanifest and early Huntington’s disease in the TRACK-HD study: Analysis of 24 month observational data. Lancet Neurol. 2012;11(1):42-53. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(11)70263-0

6. Ross CA, Aylward EH, Wild EJ, et al. Huntington disease: Natural history, biomarkers and prospects for therapeutics. Nat Rev Neurol. 2014;10(4):204-216. doi:10.1038/NRNEUROL.2014.24

7. Paulsen JS, Langbehn DR, Stout JC, et al. Detection of Huntington’s disease decades before diagnosis: The Predict-HD study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2008;79(8):874-880. doi:10.1136/JNNP.2007.128728

8. Tabrizi SJ, Scahill RI, Owen G, et al. Predictors of phenotypic progression and disease onset in premanifest and early-stage Huntington’s disease in the TRACK-HD study: Analysis of 36-month observational data. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12(7):637-649. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(13)70088-7

9. Paulsen JS, Long JD, Johnson HJ, et al. Clinical and biomarker changes in premanifest Huntington disease show trial feasibility: A decade of the PREDICT-HD study. Front Aging Neurosci. 2014;6(APR). doi:10.3389/FNAGI.2014.00078/ABSTRACT

10. Wijeratne PA, Garbarino S, Gregory S, et al. Revealing the Timeline of Structural MRI Changes in Premanifest to Manifest Huntington Disease. Neurol Genet. 2021;7(5):e617. doi:10.1212/NXG.0000000000000617

11. Kirkwood SC, Siemers E, Stout JC, et al. Longitudinal cognitive and motor changes among presymptomatic Huntington disease gene carriers. Arch Neurol. 1999;56(5):563-568. doi:10.1001/ARCHNEUR.56.5.563

12. Lemiere J, Decruyenaere M, Evers-Kiebooms G, Vandenbussche E, Dom R. Cognitive changes in patients with Huntington?s disease (HD) and asymptomatic carriers of the HD mutation. J Neurol. 2004;251(8). doi:10.1007/S00415-004-0461-9

13. Beglinger LJ, Duff K, Allison J, et al. Cognitive change in patients with Huntington disease on the Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2010;32(6):573. doi:10.1080/13803390903313564

Figures