1530

Vascular contribution to the preclinical stages of Alzheimer’s disease: Insights from the EPAD cohort1Amsterdam UMC, Amsterdam, Netherlands, 2Department of Neurology-Stroke Unit and Laboratory of Neuroscience, Istituto Auxologico Italiano IRCCS - Department of Pathophysiology and Transplantation, “Dino Ferrari” Center, Università degli Studi di Milano, Milan, Italy, Milan, Italy, 3MRC Unit for Lifelong Health and Ageing at UCL, London, UK, London, United Kingdom, 4IXICO, London, United Kingdom, 5CIRD Centre d’Imagerie Rive Droite, Geneva, Switzerland, Geneva, Switzerland, 6Department of Psychiatry and Neurochemistry, Institute of Neuroscience and Physiology, the Sahlgrenska Academy at the University of Gothenburg, Sweden, Gothenburg, Sweden, 7University Hospitals and University of Geneva, Geneva, Switzerland, 8Department of Nuclear Medicine, Toulouse CHU, Purpan University Hospital, Toulouse, France, 9Centro de Investigación y Terapias Avanzadas, Neurología, CITA‐Alzheimer Foundation, San Sebastian, Spain, 10German Center for Neurodegenerative Diseases (DZNE), Feodor-Lynen-Strasse 17, Munich, Germany, 11Université de Normandie, Unicaen, Inserm, U1237, PhIND "Physiopathology and Imaging of Neurological Disorders", Institut Blood-and-Brain @ Caen-Normandie, Cyceron, 14000, Caen, France, 12Centre for Clinical Brain Sciences, The University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, Scotland, 13Dementia Research Centre, Department of Neurodegenerative Disease, UCL Queen Square Institute of Neurology, London, United Kingdom, 14Centre for Dementia Prevention, The University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, Scotland, 15Department of Neurology, Alzheimer Center Amsterdam, Amsterdam Neuroscience, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, Amsterdam UMC, Amsterdam, Netherlands, 16Barcelonaβeta Brain Research Center (BBRC), Pasqual Maragall Foundation, Barcelona, Spain

Synopsis

Keywords: Neurodegeneration, Alzheimer's Disease, Cerebrovascular, radiological

Evidence suggests that cardiovascular risk factors and cerebrovascular disease contribute to the Alzheimer’s disease (AD) pathophysiology. It is still unclear to what extent vascular and amyloid pathology have a synergistic or independent influence in preclinical AD stages. We used structural equation models in a cohort of cognitively unimpaired individuals to investigate if cerebrovascular pathology mediates the relationship between cardiovascular risk factors and CSF Aβ1-42, and show that cerebrovascular pathology accelerates downstream AD markers (p-Tau181 and hippocampal volume) by increasing amyloid pathology.

Introduction

Epidemiological and clinical studies have shown considerable overlap between cerebrovascular disease and Alzheimer’s disease. However, it is unclear whether vascular pathology represents an independent biological event or an integrated part of the amyloid cascade, facilitating hyperphosphorylated tau (P-tau) accumulation and subsequent neurodegeneration in AD.We investigated the impact of cardiovascular risk factors and cerebral small vessel disease (CSVD) on amyloid pathology and their combined effect on the downstream AD biomarkers P-tau and hippocampal neurodegeneration.

Methods

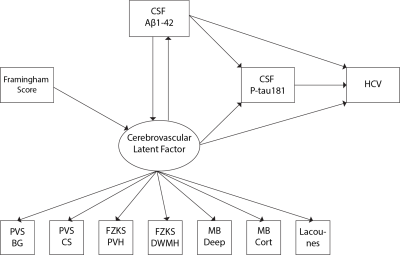

Data were drawn from the European Prevention of Alzheimer's Dementia (EPAD) cohort baseline data vIMI release (n=1592, Table 1). Cardiovascular risk was computed with the Framingham risk score (FRS). The MRI visual assessment included a 0-4 scale for PVS in the basal ganglia (BG) and centrum semiovale (CS)1, the Fazekas scale (0-3) for periventricular and deep WMHs2, presence (0-1) of lobar or deep cerebral microbleeds (CMBs3), and lacunes (0,1,2,>2), according to the STRIVE criteria4. Global and lobar periventricular and deep WMH volumes and hippocampal volumes were derived from FLAIR and T1w MRI sequences. Aβ1-42 and p-Tau181 concentrations were obtained from CSF. Linear models were used to study the association between i) FRS and CSVD; ii) FRS and Aβ1-42; iii) CSVD and Aβ1-42 and p-Tau181. We added an interaction term between CSVD indices and Aβ1-42 for predicting p-Tau181, to study possible synergic effects.Structural equation modeling (SEM) was used to model the association between 4 observed variables: FRS, Aβ1-42, P-tau181, and hippocampal volume (HCV); and one latent variable measuring the cerebrovascular component. The latent “CSVD-burden” variable was created using confirmatory factor analysis on all radiological indices. Initially, we tested the mediating effect of the CSVD-burden component in the association between FRS and Aβ1-42. Subsequently, we built a SEM model including a direct relationship of FRS with the latent CSVD-burden factor; the reciprocal relationship between the latter and Aβ1-42; the effect of both amyloid and the latent factor to P-tau181 and hippocampal atrophy; the effect of P-tau181 on hippocampal atrophy. In addition to direct effects, the model also estimated the indirect (mediating) effects of amyloid and the CSVD-burden on downstream AD markers (Figure 1).

All models were corrected for age and sex.

Results

Cohort characteristics are reported in Table 1. We observed an association between FRS and CSVD (Table 2). Higher FRS scores were also associated with lower levels of Aβ1-42 (β=-0.18; p<0.001) and higher levels of P-tau181 (β=0.21; p<0.001) and T-tau (β=0.22; p<0.001). Lower levels of Aβ1-42 were further observed in relationship with both BG (p<0.001) and CS (p<0.01) PVS; higher periventricular (p<0.001) and deep (p<0.001) Fazekas scores; the presence of lobar (β=-0.51; p<0.001) and deep (β=-0.64; p<0.05) microbleeds; the presence of 2 or more lacunes (p<0.001); and higher regional WMH volumes (all p<0.001; Figure 2)Stronger association between Aβ1-42 and P-tau181 in participants with higher Fazekas DWMH scores (coefficients per group: 0:β=-0.03, p=0.57; 1:β=-0.08, p<0.05; 2:β=-0.36, p<0.001; 3:β=-0.21, p=0.12); higher Fazekas PVH score (coefficients per group: 0:β=0.01, p=0.85; 1:β=-0.21, p<0.001; 2:β=-0.32, p<0.001; 3:β =-0.46, p<0.05); and higher regional WMH (all p<0.005) volumes were observed (Figure 3).

The CSVD-burden latent factor fully mediated the association between FRS and Aβ1-42 (direct effect: β=-0.01; p=0.34; indirect effect: β=-0.03; p<0.001). This relationship was thus not included in the subsequent model.

In the SEM model, we found a significant effect of FRS on the CSVD-burden latent component (β=-0.01; p<0.001), and a significant effect of the latter on Aβ1-42 (β=-2.64; p < 0.05). In turn, levels of Aβ1-42 were not significantly predictive of the CSVD-burden latent factor (p=0.22). We observed a significant direct effect of Aβ1-42 on P-tau181 levels (β=-0.14; p<0.001) and HCV (β=0.06; p<0.05), and of P-tau181 levels onto hippocampal volumes (β=-0.05; p<0.05). The CSVD-burden latent factor was not directly related to P-tau181 and HCV, and did not show mediating effects. However, a significant indirect effect of the latent factor on both P-tau181 (indirect effect: β =0.36; p < 0.05) and HCV (indirect effect: β=-0.24; p < 0.05) through Aβ1-42 was observed.

Conclusion

Our work shows that CSVD mediates the effect of cardiovascular risk factors on amyloid deposition, highlighting the importance of monitoring cerebrovascular pathology in patients at risk of AD. Moreover, our findings show that cerebrovascular pathology might accelerate the amyloid cascade in the preclinical phases of the disease, accelerating subsequent tau accumulation and hippocampal degeneration, stressing the importance of considering individualized vascular protective treatment for the prevention or deceleration of AD.Acknowledgements

No acknowledgement found.References

1. Potter, G. M., Chappell, F. M., Morris, Z. & Wardlaw, J. M. Cerebral perivascular spaces visible on magnetic resonance imaging: development of a qualitative rating scale and its observer reliability. Cerebrovasc. Dis. 39, 224–231 (2015).

2. Fazekas, F., Chawluk, J. B., Alavi, A., Hurtig, H. I. & Zimmerman, R. A. MR signal abnormalities at 1.5 T in Alzheimer’s dementia and normal aging. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 149, 351–356 (1987).

3. Cordonnier, C. et al. improving interrater agreement about brain microbleeds: development of the Brain Observer MicroBleed Scale (BOMBS). Stroke 40, 94–99 (2009).

4. Wardlaw, J. M. et al. Neuroimaging standards for research into small vessel disease and its contribution to ageing and neurodegeneration. The Lancet Neurology vol. 12 822–838 Preprint at https://doi.org/10.1016/s1474-4422(13)70124-8 (2013).

Figures