1526

Assessing pulsatility ratio in different sized cerebral arterial vessels across varying levels of blood pressure1Radiology&Bioengineering, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA, United States, 2Psychology, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Neurodegeneration, Hypertension

Pulsatility derived from the BOLD signal was used to assess the relationship of pulsatility damping in different sized cerebral arterial vessels across levels of blood pressure. Individuals with higher blood pressure exhibit reduced cerebrovascular compliance, and less damping of BOLD pulsatility among these individuals may be a potential indicator of cerebrovascular pathogenesis.INTRODUCTION

Increases in cerebral pulsatility may contribute to microvascular and tissue damage1. The propagation of pulsatility, i.e., damping of pulsatility from large to small arteries in the brain may be altered by cerebrovascular stiffness2,3. Less damping induces more energy deposition to the cerebral microcirculation and brain tissue. Higher systemic blood pressure (BP) can alter the cerebrovascular compliance due to increases in vascular stiffness. However, this has not been assessed across the whole brain. Recently, a method for mapping cerebral pulsatility for the whole brain has developed by extracting the amplitude of cardiac-synchronized BOLD signal fluctuations from resting-state fMRI and these fluctuations relate to reduced tissue volume in the medial temporal lobe4. Here, we tested whether BOLD pulsatility can be used to assess dampening from large to small arteries in relation to varying levels of blood pressure (BP). In addition, BOLD pulsatility was evaluated against quantitative measures of cerebrovascular blood volume (CBVa).METHODS

A total 16 participants (26-93 years old, Fe/male= 8/8) were studied at 3T. BP was determined by averaging standardized seated records before and after the MRI experiments. For anatomical information, 3D-T1-weighted images (TR/TE = 1500/3.19 ms, voxel-size = 1 mm isotropic) were acquired.CBVa quantification: Look-Locker ASL (LL-FAIR) technique was applied to measure the temporal dynamics of ASL signals using GE-EPI with 15 TIs (DTI = 259 ms) after the inversion pulse, TR/TE = 4s/31ms, flip angle = 30°°, voxel size = 3.69 x 3.69 x 4 mm, 20 slices, simultaneous multislice (SMS) acceleration factor = 5 and 40 averages5. To separate the arterial component, b = 3 and 0 s/mm2 of vascular crushing gradients were alternatively applied on three gradient axes sequentially at each slice after the excitation pulse. M0 GE-EPIs were also acquired using TR = 10s with and without crushing gradients. The dynamics of cerebral arterial blood signals were obtained by subtracting 15 ASL signals (labeling-control) with b =3 s/mm2 from those with b = 0 s/mm2. The arterial component ΔMa(t) can be expressed as ΔMa(t) = 2α·λ·M0a×CBVa×aa(t), where α:labeling efficiency (=0.95), λ: the blood-brain partition coefficient (=0.9ml/g), M0a: the equilibrium magnetization of arterial blood, CBVa: arterial blood volume (in units of ml/100g), the normalized labeled blood delivery function to the artery, aa(t) = 0.5[erf[(t-tA)/(k·t0.5)] – erf[(t-tA-τ)/(k·t0.5)]×exp(-R1aLL·t); erf: error function, tA: arterial transit time, k: dispersion constant, τ: delivery duration of labeled blood, R1aLL: effective longitudinal relaxation rate of arterial blood in LL sampling. This model was fitted to each voxel using the least-square fitting algorithm.Pulsatility: 2D GE-EPI was acquired with TR/TE = 1500/17ms, voxel size = isotropic 3.1 mm3, FA = 68°, and 42 slices with 280 volumes). The cardiac phase (θ) for each acquisition beween R-R intervals was estimated as a value between 0 and 2π using hilbert transform of the signal obtained from large arteries. See details in (4). The model of cardiac pulsation, the 2nd-order Fourier-series (s=Σi=12 ai·sin(i·θ)+bicos(i·θ)) of the cardiac phase (θ) time courses, was fit to each voxel of the imaging data with the phase corresponding to each TR and 6 motion parameters as nuisance variables. Then, cerebral pulsatility maps were computed from the coefficients (ai and bi) of the linear regression divided by its standard error (temporal variance that is not explained by fit to the model of cardiac pulsation at each voxel), using , where SE is standard error of the coefficients. Meaningful cardiac pulsatile signal was determined larger than 3s significance of the null distribution. All images were aligned and normalized to MNI space. Five percentile ranks (100-75% with 5% steps) from values in CBVa maps were obtained to determine ROI for different size of arterial vessels; large CBVa indicates large arterial vessels. Note that the same number of voxels are assigned in each ROI for all subjects because of common MNI space. All signals in CBVa ROIs are mainly arterial vessels. The pulsatility in each ROI was averaged. The ratio of the pulsatility value to the top 5% CBVa ROI was calculated for each ROI.RESULTS

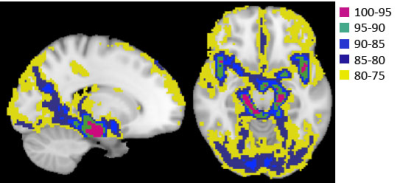

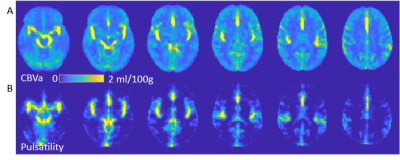

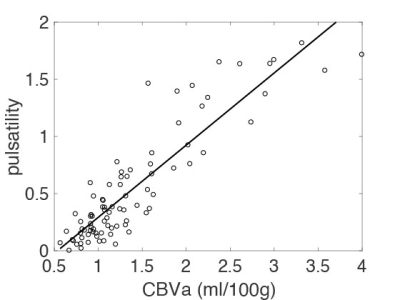

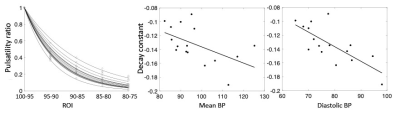

Figure 1 shows ROIs determined by CBVa values (see Fig. 2A), representing different sized arteries, from large to small. Figure 2 demonstrates quantified CBVa and pulsatility maps agree strongly. The pulsatility and CBVa values from each ROI were found to be closely related with pulsatility = 0.63×CBVa (ml/100g) – 0.33 (Fig. 3). The ratio of pulsatility was exponentially decreased from large to small arteries, and the exponential decay constant varied in each individual (Fig. 4A). This was significantly decreased with mean BP and diastolic BP (Fig. 4B and 4C), but was not significantly related with systolic BP (p=0.37, R=0.24).DISCUSSION

Hypertension is known to interfere with the ability of large cerebral arteries to dampen pulse pressure to small arteries due to increased vessel stiffness. Thus, a decrease in the decay rate in higher blood pressure indicates insufficient damping of the pulsatile pressure in the cerebral arteriesCONCLUSION

Cerebrovascular compliance can be assessed by BOLD pulsatility. Arterial hypertension induces a change in vessel dynamics. Since hypertension is known risk factor for cerebrovascular diseases, this approach may be helpful for a more comprehensive understanding of pathogenesis of cerebrovascular diseases.Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the NIH grant, P01 HL-040962. “Biobehavioral Studies of Cardiovascular Disease”References

1. Mitchell GF et al. Arterial stiffness, pressure and flow pulsatility and brain structure and function: the Age, Gene/Environment Susceptibility--Reykjavik study. Brain 2011;134(Pt 11):3398-3407.

2. Zarrinkoob L et al. Aging alters the dampening of pulsatile blood flow in cerebral arteries. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2016 Sep;36(9):1519-27.

3. Winder NR et al. Large artery stiffness and brain health: insights from animal models. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2021 Jan 1;320(1):H424-H431

4. Kim T et al. Cardiac-induced cerebral pulsatility, brain structure, and cognition in middle and older-aged adults. Neuroimage. 2021 Jun;233:117956

5. Lee Y, Kim T, Assessment of Hypertensive Cerebrovascular Alterations with multiband Look-Locker Arterial Spin Labeling J Magn Reson Imaging, 47(3):663-672, 2018

Figures