1520

MR Feature Tracking-Derived Circumferential Strain of the Aortic Wall Correlates to Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm Growth Independent of Diameter1Radiology and Biomedical Imaging, University of California, San Francisco, San Francisco, CA, United States, 2Siemens Healthineers AG, Erlangen, Germany, 3Surgery, University of California, San Francisco, San Francisco, CA, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Vessels, Vessels, Aortic Strain; MR Feature Tracking

Recent studies are increasingly highlighting aortic wall stress, strain, and other mechanical descriptors as relevant factors associated with abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) progression. The goal of this prospective patient study was to employ MR feature tracking to measure the maximum circumferential strain in AAAs and study investigate its relationship with AAA growth. The feature tracking-measured AAA circumferential strain was lower than that of the normal aorta, indicating that the AAA wall is less compliant than the non-aneurysmal aorta. Furthermore, AAA strain was associated with the growth rate of the aneurysm, independent of AAA maximum diameter.1. Introduction

Management of abdominal aortic aneurysms (AAA) is primarily determined by the maximal aneurysm diameter, the only non-systemic factor that has been associated with risk of rupture to date1,2. Recent studies are increasingly highlighting aortic wall stress, strain, and other mechanical descriptors as relevant factors associated with AAA progression3–5. Various approaches have been proposed to measure these mechanical quantities in vivo.Aortic wall strain has been assessed via speckle tracking ultrasound (US), derived from myocardial strain analysis packages, although no clear association with aneurysm outcomes and growth has emerged to date4. MR-based methods mitigate the strong operator dependence and limited field of view that generally pose challenges to such US-based analyses. MR elastography (MRE)-derived AAA stiffness was shown to associate with the composite clinical outcome of aneurysms6. However, performing MRE requires special pulse sequences and dedicated hardware, considerably limiting its availability to only a few centers around the world.

MR feature tracking is a family of techniques in which the features of cine steady-state free precession (SSFP) MR images are tracked at multiple cardiac phases to obtain tissue strain over the entire cardiac cycle7,8. Feature tracking does not require special pulse sequence or hardware, and instead utilizes routine ECG-gated cine MR images. MR feature tracking has been previously validated for myocardial strain quantification against reference-standard techniques (e.g., DENSE and tagging)9,10. The goal of this study was to employ MR feature tracking to measure the maximum circumferential strain in both AAA as well as a remote unaffected segment of the aorta (proximal to the aneurysm) throughout the cardiac cycle. We hypothesized that (1) feature tracking-derived AAA circumferential strain is lower than that of the remote unaffected aortic wall, and (2) AAA circumferential strain is associated with the AAA growth rate.

2. Methods

ECG-gated cine bSSFP MRI was acquired for 17 male AAA patients (765 years, range: 66-88 years) at a single imaging plane prescribed orthogonal to the vessel centerline at the level of maximum AAA diameter and at a second imaging plane orthogonal to the vessel centerline, proximal to the AAA where the aorta caliber is normal. Data were acquired on a 3T scanner (Skyra, Siemens Healthcare, Erlangen, Germany). Cine bSSFP parameters were: TE=1.4ms, TR=39.2ms, FOV=340×284mm2, voxel size=1.6x1.6x6mm3, flip angle=50, 25 frames/cardiac cycle.MR feature tracking was performed using a work-in-progress software package TrufiStrain (Siemens Healthcare, Erlangen, Germany). In the software, strain values are derived from the deformation fields which are computed based on an efficient symmetric and inverse-consistent deformable registration method11. The difference between the systolic and diastolic circumferential strains was calculated and reported as the maximum circumferential strain through the R-R interval.

The retrospective growth rate of each AAA was measured from prior CT and MR clinical studies up to two years before the cine MRI. For each study, maximal AAA diameter was measured using Vitrea (Canon Medical, Minnetonka, MN) in the plane orthogonal to the AAA centerline in both reformatted sagittal and coronal views. Univariate regression was then used to associate the aneurysm wall strain with AAA growth rate. Additionally, a multivariate regression was performed to associate strain with AAA growth rate controlling for maximum diameter.

3. Results

On average, subjects underwent 2.7±0.9 imaging exams from which AAA growth rate could be calculated, including the MRI cine study. The average AAA maximum diameter at the time of the cine MRI studies was 43.0±9.9mm and the average 2-year growth rate was 1.9±1.2mm/year.Figure 1 demonstrates the MR-feature tracking-measured circumferential wall strain in a representative AAA and the corresponding normal caliber segment of aorta for the same subject, over the cardiac cycle. (Figure 1a). The 2-year growth rate for this subject was 1.13mm/year (Figure 1b).

The mean peak circumferential strain through the R-R interval was 1.3±0.8% in the AAA sac and 3.1±2.3% in the non-aneurysmal aorta. The difference between the AAA and normal caliber aorta peak strain was 1.76% (95% CI: [0.70 2.82]) and was statistically significant (P=.0029).

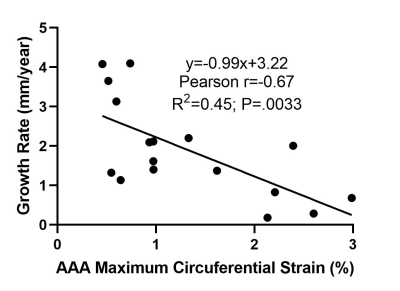

In univariate analysis, the maximum strain through the R-R interval and growth rate in the preceding 2 years were statistically significantly associated (coefficient=-0.993, 95% CI: [-1.60 -0.39], P=.0033, N=17). This inverse correlation was strong as shown in Figure 2 (Pearson r=0.67). After controlling for the maximum diameter in multivariate analysis, maximum strain remained statistically significantly associated with growth rate (coefficient=-0.719, 95% CI: [-1.42 -0.02], P=.044, N=17).

4.Conclusion

This work demonstrated the feasibility of using MR feature tracking to measure aortic strain in AAA patients, providing an accessible and non-invasive tool for assessing the biomechanical properties of AAAs. The feature tracking-measured AAA circumferential strain was lower than that of the normal aorta, indicating that the AAA wall is less compliant than the non-aneurysmal aorta. Furthermore, AAA strain was associated with the growth rate of the aneurysm, independent of AAA maximum diameter, with AAA exhibiting a higher strain throughout the cardiac cycle having experienced a slower progression compared to AAA exhibiting a lower strain. These results suggest feature tracking-based strain may be a novel marker for risk stratifying AAA patients. Future work is warranted to investigate the relationship between MR feature tracking-derived aortic strain and clinical outcomes in a large patient cohort.Acknowledgements

No acknowledgement found.References

1. Brewster DC, Cronenwett JL, Hallett JW, Johnston KW, Krupski WC, Matsumura JS. Guidelines for the treatment of abdominal aortic aneurysms: Report of a subcommittee of the Joint Council of the American Association for Vascular Surgery and Society for Vascular Surgery. J Vasc Surg. 2003;37(5):1106-1117. doi:10.1067/mva.2003.363

2. Scott R. The Multicentre Aneurysm Screening Study (MASS) into the effect of abdominal aortic aneurysm screening on mortality in men: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2002;360(9345):1531-1539. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11522-4

3. Vorp DA, Geest JP Vande. Biomechanical Determinants of Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm Rupture. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005;25(8):1558-1566. doi:10.1161/01.ATV.0000174129.77391.55

4. Indrakusuma R, Jalalzadeh H, Planken RN, et al. Biomechanical Imaging Markers as Predictors of Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm Growth or Rupture: A Systematic Review. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2016;52(4):475-486. doi:10.1016/j.ejvs.2016.07.003

5. Bappoo N, Syed MBJ, Khinsoe G, et al. Low Shear Stress at Baseline Predicts Expansion and Aneurysm-Related Events in Patients With Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2021;14(12):1112-1121. doi:10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.121.013160

6. Dong H, Raterman B, White RD, et al. MR Elastography of Abdominal Aortic Aneurysms: Relationship to Aneurysm Events. Radiology. 2022;304(3):721-729. doi:10.1148/RADIOL.212323

7. Schuster A, Hor KN, Kowallick JT, Beerbaum P, Kutty S. Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance Myocardial Feature Tracking. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2016;9(4). doi:10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.115.004077

8. Dobrovie M, Barreiro-Pérez M, Curione D, et al. Inter-vendor reproducibility and accuracy of segmental left ventricular strain measurements using CMR feature tracking. Eur Radiol. 2019;29(12):6846-6857. doi:10.1007/s00330-019-06315-4

9. Goto Y, Ishida M, Takase S, et al. Comparison of Displacement Encoding With Stimulated Echoes to Magnetic Resonance Feature Tracking for the Assessment of Myocardial Strain in Patients With Acute Myocardial Infarction. Am J Cardiol. 2017;119(10):1542-1547. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2017.02.029

10. Backhaus SJ, Metschies G, Zieschang V, et al. Head‐to‐head comparison of cardiovascular MR feature tracking cine versus acquisition‐based deformation strain imaging using myocardial tagging and strain encoding. Magn Reson Med. 2021;85(1):357-368. doi:10.1002/mrm.28437

11. Guetter C, Xue H, Chefd’hotel C, Guehring J. Efficient symmetric and inverse-consistent deformable registration through interleaved optimization. In: 2011 IEEE International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging: From Nano to Macro. IEEE; 2011:590-593. doi:10.1109/ISBI.2011.5872476

Figures