1510

The impact of intracranial atherosclerotic on the load and progress of cerebral small vessel disease1radiology, Beijing Chaoyang Hospital of Capital Medical University, Beijing, China

Synopsis

Keywords: Vessel Wall, Brain

This study hypothesized that the load and the progression of cSVD in the unilateral hemisphere is correlated with the features of ipsilateral intracranial large arterial vessel wall lesions. Using the fluctuations of WHMs at baseline and follow-up to reflect the severity of cSVD. VW-HRMRI, the most sensitive non-invasive ways to evaluate the lesions of intracranial vascular, was used to assessment the morphological and enhancement characteristic of the culprit plaque. The result suggested that mild stenosis and positive remodeling of MCA may associated with WHM progression.Introduction

Cerebral small vessel disease (cSVD) is a term of dysfunction or disorder of the whole brain caused by vascular abnormalities at the level of microcirculation, often occurring in parallel with intracranial atherosclerosis (ICA)[1, 2]. This study hypothesizes that the altered hemodynamics associated with the lesions of the intracranial large artery can adversely affect the distal small vessels. Using high-resolution MR vessel wall imaging (VW-HRMRI) to visualize the vessel wall of the proximal middle cerebral artery (M1-2 segment)[3], and exploring the combination between plaque features in ICA and the severity and progression of cSVD.Methods

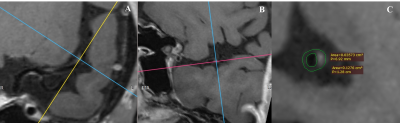

This is a retrospective cohort study using the clinical and imaging data of 40 patients with symptomatic atherosclerotic lesions who accepted the VW-HRMRI and at least two conventional brain MR. VW-MRI was performed both pre- and post-contrast administration by using a 3D T1-weighted vessel wall MRI sequence known as inversion-recovery (IR) prepared SPACE on a 3.0-T MAGNETOM Prisma 3.0T MR scanner (Siemens Healthcare, Erlangen, Germany) with a 64-channel head-neck coil (Prisma). And the follow-up imaging was acquired more than three months after the baseline (from 3.9 to 51.87months, 25 months on average). The most stenotic lesion on the M1-2 segment of MCA was defined as the culprit plaque, and morphological and enhancement features of them were obtained by manually tracing and measuring on reconstructed cross-sectional imaging of VW-HRMRI (Figure 1). The vessel area (VA) and lumen area (LA) of the corresponding segment were used to calculate the normalized wall index (NWI) as (VA-LA)/VA to reflect the plaque’s load. And vessel remodeling contributed by ICA was quantified by remodeling index (RI), computed by the ratio of plaque VA and the corresponding reference segment VA. RI >1.05 was defined as positive remodeling and RI <0.95 was defined as negative remodeling[4]. Since white matter hyperintensities (WMH) is the most sensitive visualization imaging marker for cSVD[5], using the standardized volume and visual score (proposed by Schmidt[6]) of WMH derived from T2-FLAIR to reflect the severity of cSVD. The WMH were classified into deep (dWMHs), periventricular (pWMHs) and total (tWMHs) lesions and assessed separately within each hemisphere of the brain[7, 8]. Calculating the average value of the WMH score change between baseline and follow-up examinations in 40 patients, total 80 hemicerebrums. The hemicerebrums with above-average development of WMH score were defined as the WMH progression group and the rest as the non-progression group. The relationship between the unilateral burden of WMH, ipsilateral proximal MCA plaque features, and vascular risk factors was assessed by using linear regression. Correlation analysis and logistic regression were used to assess the correlation between the progression of WMH and ICA imaging metrics within the hemicerebrum.Results

Cross-sectional analysis showed that age, hypertension and a history of smoking were associated with the score of WMH lesions(p<0.005), while none of the imaging metrics of MCA plaque reaches statistical significance. Despite the mean values and distribution ranges of the tWMHs and dWMHs scores were higher in the ipsilateral hemisphere with plaque enhancement than those without through bar chart ocularly (Graph 1). And the scatter plot (Graph 2) shows liner dependent roughly between the hemispheres’ NWI and volume of dWMHs. In the comparison between the subgroups, hypertension (OR 6.344, 95%CL 1.702-23.647, p=0.006), history of symptomatic stroke (OR 5.743, 95%CL 1.823-18.097, p=0.003) and mild (0%–50%) stenosis (OR 5.287,95%CL 1.089-25.661, p=0.039) were associated with the development of WMH. Besides, compared with positive remodeling, negative remodeling could be a protective factor for WMH progression (OR 0.173, 95%CL 0.036-0.824, p=0.028).Discussion

No statistical association was found between the plaques’ features of ICA to the burden of ipsilateral WMH in baseline demonstrating that the influence proximal intracranial artery lesions exert on the downstream small vessel bed is complex, so that is hard to analyze by cross-sectional study[9]. By observing the dynamic change of WMH, we found that mild atherosclerotic stenosis and positive remodeling of MCA are more likely to result in the progress of ipsilateral WMH. Firstly, we presumed that the chronic hemodynamic changes and cytokine release accompanied by mild stenosis may contribute to the potential progression of distal small vessel lesions, while moderate-to-severe stenosis is more likely to cause an acute stroke. Secondly, a study about artery remodeling in coronary presented that while positive remodeling may mitigate the effects of hemodynamic changes[10], it may be associated with adverse prognosis. Our research suggested these two remolding patterns of proximal intracranial arteries may affect the downstream small vessel differentially through similar mechanisms. Besides, hemispheres with a previous stroke are more likely to have cSVD disease progression implying that the structural changes of brain tissue and the dysfunction of blood-brain barrier after stroke may adversely impact microcirculation continually[11].Conclusions

Age, hypertension and smoking history are significant vascular risk factors of cSVD. Intracranial atherosclerotic stenosis may accelerate the progression of cSVD, and positive remodeling may contribute to the more rapid progression of WMH.Acknowledgements

No acknowledgement found.References

[1]. Wong, L.K., Global burden of intracranial atherosclerosis. Int J Stroke, 2006. 1(3): p. 158-9.

[2]. Lee, S.J., et al., The leukoaraiosis is more prevalent in the large artery atherosclerosis stroke subtype among Korean patients with ischemic stroke. BMC Neurol, 2008. 8: p. 31.

[3]. Mossa-Basha, M., et al., Multicontrast high-resolution vessel wall magnetic resonance imaging and its value in differentiating intracranial vasculopathic processes. Stroke, 2015. 46(6): p. 1567-73.

[4]. Qiao, Y., et al., Patterns and Implications of Intracranial Arterial Remodeling in Stroke Patients. Stroke, 2016. 47(2): p. 434-40.

[5]. Smith, E.E. and H.S. Markus, New Treatment Approaches to Modify the Course of Cerebral Small Vessel Diseases. Stroke, 2020. 51(1): p. 38-46.

[6]. Scheltens, P., et al., A semiquantative rating scale for the assessment of signal hyperintensities on magnetic resonance imaging. J Neurol Sci, 1993. 114(1): p. 7-12.

[7]. Fan, X., et al., Cerebral Small Vessel Disease Burden Related to Carotid Intraplaque Hemorrhage Serves as an Imaging Marker for Clinical Symptoms in Carotid Stenosis. Front Neurol, 2021. 12: p. 731237.

[8]. Ni, L., et al., The Asymmetry of White Matter Hyperintensity Burden Between Hemispheres Is Associated With Intracranial Atherosclerotic Plaque Enhancement Grade. Front Aging Neurosci, 2020. 12: p. 163.

[9]. Park, J.H., et al., Association of intracranial atherosclerotic stenosis with severity of white matter hyperintensities. Eur J Neurol, 2015. 22(1): p. 44-52, e2-3.

[10]. Varnava, A.M., P.G. Mills and M.J. Davies, Relationship between coronary artery remodeling and plaque vulnerability. Circulation, 2002. 105(8): p. 939-43.

[11]. Villringer, K., et al., DCE-MRI blood-brain barrier assessment in acute ischemic stroke. Neurology, 2017. 88(5): p. 433-440.

Figures

Figure 1. A representative case of patient with atherosclerotic stenosis.

(A)VW-HRMRI showed the culprit plaque is located at the beginning of the M2 segment.

(B)The cross-sectional imaging help to find the narrowest section of the plaque.

(C)A focal plaque with moderate stenosis, positive remodeling (remodeling index = 1.27) and without significantly enhancement. The plaque-wall contrast ratio and NWI were 1.05, 0.72, respectively.