1496

Clinical assessment of noise corrected exponentially weighted diffusion weighted MRI (niceDWI) for imaging patients with metastatic melanoma

Annemarie Knill1,2, Matthew Blackledge1, Jessica Winfield1,2, Hannah Barnsley2, Benjamin Malawo2, Georgina Hopkinson2, Dow-Mu Koh1,2, Samuel Withey2, and Christina Messiou1,2

1The Institute of Cancer Research, London, United Kingdom, 2The Royal Marsden NHS Foundation Trust, London, United Kingdom

1The Institute of Cancer Research, London, United Kingdom, 2The Royal Marsden NHS Foundation Trust, London, United Kingdom

Synopsis

Keywords: Cancer, Diffusion/other diffusion imaging techniques

Systematic clinical validation of noise-corrected, exponentially-weighted, diffusion-weighted MRI (niceDWI) is performed in metastatic melanoma including soft tissue disease. Previous assessments of niceDWI demonstrated improvement in the in-plane bias field. No clinical advantage is found over clinical DWI: the signal-to-noise ratio was assessed as significantly worse in niceDWI both quantitatively and by an experienced reader; there was no difference demonstrated in the contrast-to-noise ratio (CNR) of bone or nodal lesions; when soft tissue disease is included CNR is significantly worse on niceDWI. It is recommended that future evaluations of niceDWI assess the maximum intensity projection for use as a survey tool.Introduction

Noise-corrected, exponentially-weighted, diffusion-weighted MRI (niceDWI) has been proposed as a method for improving the standardisation of whole-body diffusion-weighted imaging (WB-DWI) using estimates of the apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) and ADC uncertainty [1]. Visual assessments of niceDWI in patients with metastatic prostate cancer (where 90% of metastases are found in bone [2]) have demonstrated improvement in the in-plane bias field compared with clinical WB-DWI. However, this result was not clinically verified. In this work, niceDWI is tested in patients with metastatic melanoma (MM) where metastatic disease in soft tissues such as lungs, brain, liver and bowel is common [3]. This work presents a first systematic evaluation of niceDWI in MM to assess the performance of the technique in a disease type which commonly includes metastases in soft tissues.Methods

WB-DWI was acquired in 20 patients with unresectable stage III or IV melanoma at baseline, prior to immunotherapy. Imaging was performed on a 1.5T scanner (MAGNETOM Aera, Siemens Healthcare, Erlangen, Germany) with b-values 50, 600, 900 s/mm2 and multi-directional diffusion-weighting gradients, with 12 diffusion-encoding directions at each b-value. Images were acquired using seven stations, covering vertex to the knees. Clinical DWI (clinDWI) was derived from the geometric average of the 12 repeated acquisitions at b=900 s/mm2 and niceDWI was calculated using$$S_{nc}(a,b)=\exp{(-a*\sigma_{ADC})}\exp{(-b*ADC)}$$

with a=2x104, b=900 s/mm2, and estimates of the ADC and ADC uncertainty (σADC) derived from an iterative weighted linear least-squares estimation to the log transform of DWI data at all b-values [1].

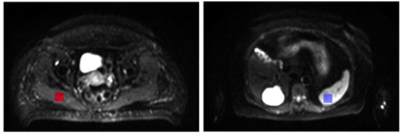

75 lesions were delineated in all patients and two 4cm2 regions of interest (ROIs) were drawn in healthy muscle and spleen in each patient (Figure 1). Patients included in this study presented with metastases to the nodes(number of lesions, n=17), bone(n=14), liver (n=8), lung(n=8), muscle(n=6), brain(n=6), subcutaneous tissues(n=5), pancreas(n=3), retroperitoneum(n=3), gallbladder(n=2), bladder(n=1), adrenal gland(n=1) and nasal cavity(n=1).

The signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) was calculated by dividing the average signal in the healthy muscle by the standard deviation of the signal in the same ROI. The contrast-to-noise ratio (CNR) was calculated for healthy spleen, bone and nodal lesions separately and all 75 lesions together by taking the difference in the average signal intensity of the ROIs and the healthy muscle ROI and dividing by the standard deviation of the signal in the muscle. Values of the CNR and SNR were calculated in both niceDWI and clinDWI. Wilcoxon signed-rank (WSR) tests were performed to test for a difference between the SNR and CNR of the two methods, with p<0.05 observed as significant.

Both niceDWI and clinDWI images were qualitatively scored by a single reader (with 4 years’ experience in WB-DWI) for SNR, CNR, presence of image artefacts and overall image quality on a scale from 1 to 5, where 1=undiagnostic, 2=poor, 3=average, 4=good, and 5=excellent. The image-types and patients were randomised and divided between two reads with one week between readings from the same patient. WSR tests were performed to test for a difference between the scores on the two methods, with p<0.05 observed as significant.

Results

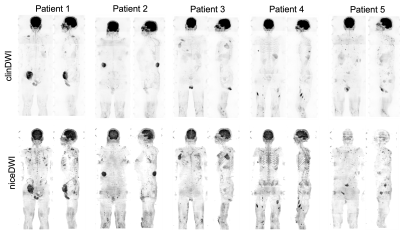

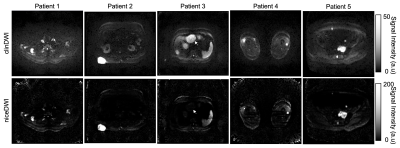

Maximum intensity projections (MIPs) of the niceDWI and corresponding clinDWI are shown in Figure 2 for 5 patients. An axial slice of niceDWI and clinDWI from each of these 5 patients is shown in Figure 3.The SNR in healthy muscle was significantly higher in the clinDWI than in niceDWI (WSR, p-value<0.05). When comparing the CNR of all lesions together it was also significantly higher in clinDWI compared to niceDWI (p-value<0.05), and when comparing the CNRs of healthy spleen (p-value=2x10-6). However, the difference in the CNR of bone and nodal disease separately on niceDWI was not significantly different to clinDWI (p-values 0.1 and 0.2 respectively).

From the clinical evaluation of the imaging the SNR, CNR, presence of image artefacts and overall image quality were assessed as consistently better in clinDWI than niceDWI (all p-values<0.05).

Discussion

Both quantitative measurements of the SNR and clinical validation of the imaging showed that the SNR is significantly decreased when using niceDWI. Furthermore, when all lesions including soft-tissue disease are included in the analysis, clinDWI presents significantly better CNR. However, the CNR of bone and nodal lesions is quantitatively assessed to be of comparable quality for both techniques, suggesting that niceDWI is less effective for imaging cancers likely to metastasise to soft tissues. In future work, further clinical validation assessing site-specific sensitivity and specificity would be useful to validate this result.Although these results clearly indicate that niceDWI cannot be used to replace clinDWI, the technique appeared to show improved inter-station homogeneity when the images are viewed as MIPs. Therefore, it may provide benefit as a survey tool for assessing the distribution of disease or potentially within pipelines for automatic segmentation.

Conclusion

Clinical validation of niceDWI shows no clear clinical advantage over clinDWI: the SNR was assessed as significantly worse in niceDWI both quantitatively and subjectively by an experienced reader; there was no difference demonstrated in the CNR of bone or nodal lesions; and when soft tissue disease is included, CNRs are significantly worse in niceDWI. It is recommended that future evaluations of niceDWI assess the MIP for use as a survey tool.Acknowledgements

This work represents independent research funded by the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) Biomedical Research Centre and the Clinical Research Facility in Imaging at The Royal Marsden NHS Foundation Trust and the Institute of Cancer Research, London. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.References

1. Blackledge MD, Tunariu N, Zugni F, et al (2020) Noise-Corrected, Exponentially Weighted, Diffusion-Weighted MRI (niceDWI) Improves Image Signal Uniformity in Whole-Body Imaging of Metastatic Prostate Cancer. Front Oncol 10:704.

2. Bubendorf L, Schöpfer A, Wagner U, et al (2000) Metastatic patterns of prostate cancer: An autopsy study of 1,589 patients. Hum Pathol 31:578–583.

3. Damsky WE, Rosenbaum LE, Bosenberg M (2011) Decoding melanoma metastasis. Cancers 3:126–163.

Figures

Figure 1: Examples of ROIs drawn on the DWI in the healthy muscle (left) and spleen (right) to estimate the SNR and CNR.

Figure 2: Examples of maximum intensity projections (MIPs) of clinical DWI (clinDWI) at b-value=900s/mm2 averaged from 12 acquisitions and noise-corrected, exponentially-weighted, diffusion-weighted MRI (niceDWI) in 5 patients. niceDWI appear to show better inter-station homogeneity compared to clinDWI.

Figure 3: Examples of a single slice from axial clinical DWI (clinDWI) at b-value=900 s/mm2 averaged from 12 diffusion-encoding directions and niceDWI in 5 patients. SNR, CNR, presence of image artefacts and overall image quality were clinically evaluated as significantly better in clinDWI. Quantitative estimates of CNR of bone and nodal lesions were not significantly different. The white arrow on scan of patient 3 shows how signal intensity of liver lesions is decreased in niceDWI due to increased ADC uncertainty from breathing motion.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.58530/2023/1496