1492

A pH-sensitizer can improve cancer immunotherapy treatment as monitored with acidoCEST MRI

Renee L Chin1,2, Jorge de la Cerda1, F William Schuler3, Sanhita Sinharay4, and Mark D Pagel1

1Cancer Systems Imaging, UT MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX, United States, 2Immunology, MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX, United States, 3Cancer Systems Imaging, MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX, United States, 4Center for Biosystems Science and Engineering, Indian Institute of Science, Bangalore, India

1Cancer Systems Imaging, UT MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX, United States, 2Immunology, MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX, United States, 3Cancer Systems Imaging, MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX, United States, 4Center for Biosystems Science and Engineering, Indian Institute of Science, Bangalore, India

Synopsis

Keywords: Cancer, CEST & MT, immunotherapy

Tumor acidosis causes resistance to immune checkpoint blockade (ICB) immunotherapy. We have identified a “pH-sensitizer” that increases the extracellular pH of the tumor microenvironment, improving immunogenicity and tumor control with ICB. AcidoCEST MRI can measure the extracellular pH of the tumor microenvironment. We used acidoCEST MRI to correlate the increase in tumor pHe immediately caused by the pH-senstizer with the tumor volume at study endpoint, in a pre-clinical model of breast cancer. These results show that acidoCEST MRI can contribute to predicting the outcome of immunotherapy.INTRODUCTION

Tumor acidosis causes resistance to immune checkpoint blockade (ICB), primarily by inhibiting T cell activation in the tumor microenvironment.1 Reducing tumor acidosis by inhibiting mechanisms of extracellular acidification may improve the effect of immunotherapy.2 We refer to these inhibitors as “pH-sensitizers”. AcidoCEST MRI can longitudinally measure extracellular pH (pHe) in the tumor microenvironment.3 Therefore, acidoCEST MRI may be able to evaluate the early response to pH-sensitizers to ensure that the tumor has been sufficiently sensitized before starting ICB treatment.MATERIALS and METHODS

To perform in vitro studies, we screened a panel of small molecule inhibitors that target 4T1 and tumor cell mechanisms that acidify the tumor microenvironment. We used a Seahorse instrument to measure the proton efflux rate and extracellular acidification rate. We also tested the toxicity of each inhibitor against 4T1 tumor cells and T cells, and we evaluated T cell inactivation after treatment with each inhibitor.To perform in vivo studies, we treated a 4T1 orthotopic tumor model with esomeprazole (a VATPase inhibitor) and immune checkpoint blockade (anti-CTLA-4 and anti-PD-1), with 0, 1, and 3 days between treatment with the inhibitor vs. ICB. We also tested esomeprazole, ICB, and no treatment as controls. We monitored tumor volume and survival following treatment. We also performed flow cytometry to characterize the T cell infiltration and activation in tumors. In a separate in vivo study, we used acidoCEST MRI to measure tumor pHe 1 day after administering esomeprazole to the 4T1 model.

RESULTS

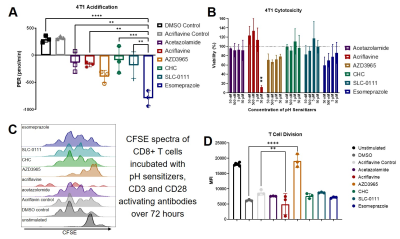

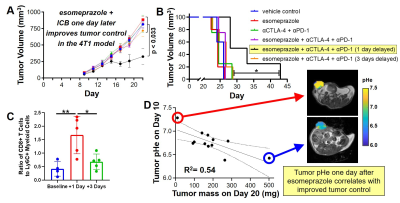

The in vitro studies identified esomeprazole as the best inhibitor for raising tumor pHe, while causing no significant toxicity to tumor cells or T cells, and without inhibition of T cell activation (Figure 1). The in vivo studies showed that esomeprazole followed one day later with ICB significantly delayed tumor growth and increased survival, while combinations with different timings did not significantly improve treatment effect, and treatments with only esomeprazole or ICB also showed no significant effect (Figure 2). The effective combination of esomeprazole followed 1 day by ICB increased the intratumoral ratio of CD8+ T cell to Ly6C+ myeloid cells, showing that esomeprazole enhanced T cell activity.AcidoCEST MRI measurements of tumor pHe 1 day after administering esomeprazole revealed a range of increases in pHe among the tested tumors, indicating variability in response to esomeprazole. This variability in pHe response was an advantage in our study, because the mass of 4T1 tumors treated with esomeprazole and ICB negatively correlated with tumor pHe measured 1 day of esomeprazole treatment.

DISCUSSION

Our results demonstrate that a single dose of esomeprazole can improve tumor control with ICB. However, testing multiple doses of esomeprazole is warranted, and other pH-sensitizers should also be tested, to optimize the pH-sensitization prior to starting ICB treatment. Testing other tumor cell types is especially warranted to investigate the robustness of this approach for improving immunotherapy against many cancer types. Furthermore, the effect of esomeprazole on tumor pHe measured 1 day after treatment was variable, suggesting that acidoCEST MRI measurements of tumor pHe at earlier or later time points may be needed to monitor the longitudinal effect of a pH-sensitizer.CONCLUSIONS

A pH-sensitizer can improve cancer immunotherapy treatment as monitored with acidoCEST MRI.Acknowledgements

Our research is supported by the NIH/NCI through grants R01 CA231513 and P30 CA016672.References

1. Gerweck LE, Seetharaman K. Cellular pH gradient in tumor versus normal tissue: potential exploitation for the treatment of cancer. Cancer Res 1996;56:1194-1198.

2. Pilon-Thomas S, et al. Neutralization of Tumor Acidity Improves Antitumor Responses to Immunotherapy. Cancer Res, 2016;76:1381-1390.

3. Chen LQ, et al. Evaluations of extracellular pH within in vivo tumors using acidoCEST MRI. Magn Reson Med, 2014;72:1408-1417.

Figures

Figure 1. Esomeprazole is a “pH-sentitizer”. A) A Seahorse assay showed that esomeprazole caused

the largest decrease in proton efflux rate (PER) among all inhibitors that were

tested against 4T1 breast tumor cells.

B) Esomeprazole did not cause dose-dependent toxicity against 4T1 tumor

cells. C,D) Esomeprazole did not affect T cell differentiation.

Figure 2. A pH-sensitizer improves tumor control with immunotherapy. Esomeprazole followed one day later by immune

checkpoint blockade (ICB) A) reduced tumor growth and B) improved survival in

the 4T1 model relative to other treatment paradigms. C) Esomeprazole followed

by ICB one day later improved immunogenic cell infiltrate in the tumor. D) The extracellular pH (pHe) measured with

acidoCEST MRI after esomeprazole treatment was correlated with tumor volume

after ICB.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.58530/2023/1492