1485

Automated Segmentation of Multi-Vendor Kidney Images using an Iteratively Trained Convolutional Neural Network1Sir Peter Mansfield Imaging Centre, University of Nottingham, Nottingham, United Kingdom, 2Institute for Lung Health, Leicester NIHR Biomedical Research Centre, University of Leicester, Leicester, United Kingdom, 3Division of Cardiovascular Medicine, Radcliffe Department of Medicine, Oxford University, Oxford, United Kingdom, 4Oxford University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, Oxford University, Oxford, United Kingdom

Synopsis

Keywords: Kidney, Segmentation

Measures of total kidney volume (TKV) help to evaluate disease progression, and masks to define the kidney are important for the automatic assessment of multiparametric images collected in the same data space. For accurate measures in multicentre studies an automated method which is vendor agnostic and robust against image artefacts is needed. Here a single-vendor convolutional neural network is retrained and shown to be accurate on two vendors of scanner and robust against image artefacts associated with wrapping in the phase-encode direction.

Introduction

Measures of total kidney volume (TKV) help to evaluate disease progression, and masks to define the kidney are important for the automatic assessment of multiparametric images collected in the same data space. However, manual estimation is time consuming. Here, a deep-learning algorithm is used to analyse multi-site, two vendor data, and iteratively trained to increase robustness to underlying image artefacts which can cause erroneous masks leading to inaccuracies in the estimation of TKV.Methods

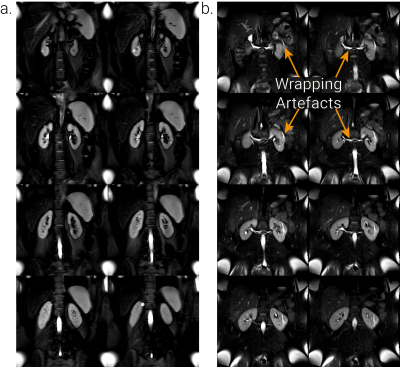

MRI AcquisitionThe dataset comprised 250 subjects 3T T2-weighted FSE scans1 collected across two vendors (Siemens (Prisma/Skyra/Vida) and Philips (Achieva/Ingenia), henceforth randomly labelled Vendor 1 and 2) with similar protocols (TE≈60ms, refocus angle=120°, bandwidth=781Hz, FOV=384×384mm2, voxel size=1.5×1.5×5mm3, whole kidney coverage coronal slices). In addition, scans were collected on 9 healthy volunteers (HVs) on both vendors (Siemens Prisma/Philips Ingenia) to allow assessment of cross-vendor repeatability of TKV. Wrapping artefacts were noted in ~39% of the Siemens (predominantly Skyra/Vida) data sets due to the phase encoding in the foot-head (FH) rather than anterior-posterior (AP) direction. Example data is shown in Figure 1.

Automated Segmentation

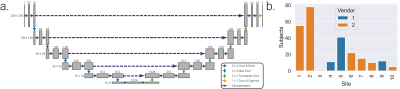

Segmentation was initially based on a network2 using weights3 trained on solely Philips datasets (defined as the ‘pretrained network’); an overview of the convolutional neural network (CNN) architecture and distribution of subjects across sites and vendors is shown in Figure 2. Upon visual inspection it was evident that a wrapping artefact impacted the accuracy of automated segmentations in some Siemens data sets, the CNN was therefore retrained using both Philips and Siemens datasets including those with and without wrapping artefacts.

To generate gold standard masks for retraining the network, rather than perform very time-consuming manual segmentation of all 250 scans, the CNN was retrained iteratively. First a small number (~20%) of the automatic masks generated using the pretrained CNN were manually corrected, this greatly reduced the manual segmentation times while still maintaining high-quality masks. These masks were then used to retrain the CNN, a next batch of unseen data was then segmented using the last trained CNN. This process was iteratively repeated until masks of all subjects had been manually corrected. The CNN was trained a final time using all 250 subjects (58 Philips, 192 Siemens) and their corresponding manually corrected masks. Through each stage of the retraining process 90% of subjects were used as training data and 10% as validation data.

The HV repeatability dataset of subjects scanned on both vendors was used to test the ‘Retrained Network’ on unseen data. Both the pretrained and retrained networks were evaluated against manually corrected masks.

Statistical Analysis

The similarity between automated masks and manually corrected masks was assessed using Dice and Jaccard scores, mean surface distance (MSD) and total kidney volume (TKV) difference. The repeatability between vendors and agreement between segmentation methods was assessed using a repeated measurement analysis of variance (rmANOVA) test. A one-way-ANOVA test was used to assess the data for significant performance differences across vendors.

Results

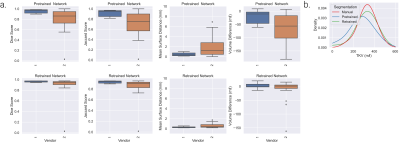

Example kidney masks produced by the Retrained Network are shown in Figure 3, comparison of Fig. 3b and 3c qualitatively shows the improvement in segmentation accuracy offered by the Retrained Network against the manually corrected masks. This is demonstrated by the increased Dice and Jaccard scores, and decreased MSD and TKV difference for the Retrained Network compared to the Pretrained Network, Fig. 4a. A significant improvement in Dice, Jaccard and TKV difference was observed using the Retrained Network (p=0.005, 0.004, 0.0003 respectively). A significant difference between the manual TKV and automatic TKV was observed when using the Pretrained Network (p=0.00007), this was insignificant when using the Retrained Network (p=0.21), Fig. 4b. No significant difference in measured TKV or segmentation accuracy was reported between vendors using the Retrained Network across vendors.When assessing the HV repeatability dataset, no significant difference in estimated TKV or segmentation accuracy metrics was observed between vendors, as summarised in Figure 5.

Discussion

Manual segmentation of the kidneys of large cohorts, such as the 250 subjects here, would be time consuming and prone to errors. Here, a CNN is iteratively trained using the correction of sub-optimal automatically generated masks including those suffering from wrapping artefacts. Retraining the CNN iteratively with all available data resulted in the reduction in manual correction times as the dataset was processed due to the progressively increased automated accuracy.A significant improvement in segmentation accuracy metrics was observed as a result of the retraining process due to the CNN being better able to segment data with wrapping artefacts. This led to the difference in measured TKV from manual corrected measurements being insignificant.

The degree of underestimation in TKV reported in this work for the CNN compared to the manually corrected masks is in agreement with that reported when using the same architecture on a single vendor compared to fully manually drawn masks2,3.

Conclusion

An existing CNN was retrained to segment the kidneys using a large cohort of patients and shown to be robust to imaging artefacts and vendor agnostic in its estimation of TKV.Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Medical Research Council and Department of Health and Social Care/National Institute for Health Research Grant (MR/V027859/1) ISRCTN number 10980107. We gratefully acknowledge the support of NVIDIA Corporation with the donation of the Titan Xp GPU used for this research.References

1. Will S, Martirosian P, Würslin C, Schick F. Automated segmentation and volumetric analysis of renal cortex, medulla, and pelvis based on non-contrast-enhanced T1- and T2-weighted MR images. Magn. Reson. Mater. Phys. Biol. Med. 2014;27:445–454 doi: 10.1007/s10334-014-0429-4.

2. Daniel AJ, Buchanan C, Morris DM, et al. Generalisability of Automated CNN-based Renal Segmentation for Multi-Vendor Studies. In: Proc. Intl. Soc. Mag. Reson. Med. 30. London; 2022. p. 2160.

3. Daniel AJ, Buchanan CE, Allcock T, et al. Automated renal segmentation in healthy and chronic kidney disease subjects using a convolutional neural network. Magn. Reson. Med. 2021;86:1125–1136 doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/mrm.28768.

Figures

Figure 3: Example T2-weighted FSE acquisitions superimposed with automated masks (red), manual corrected masks (blue) and overlap of automated and manual masks (magenta). a. Automated masks generated using the retrained CNN for the subject shown in Fig 1a. b. Automated masks generated using the pretrained network for the subject shown in Fig 1b, c. Automated masks generated using the retrained network for the subject shown in Fig 1b.

Figure 5: Comparison of results of the Pretrained and Retrained network to segment nine unseen healthy volunteers, each scanned on both Vendor 1 and Vendor 2. a. Correlation in Total Kidney Volume (TKV) between vendors for manual segmentation, the Pretrained Network and Retrained Network and Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r). b. Comparison of accuracy metrics between manual and automated masks generated from the Pretrained and Retrained Networks for Vendor 1 and 2.