1462

Quantification of CSF T1 and T2 in the Subarachnoid Space: Implication for Brain-CSF Exchange1Department of Radiology, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, United States, 2Department of Biomedical Engineering, Johns Hopkins University School of Engineering, Baltimore, MD, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Neurofluids, Neurofluids

It has been suggested that the brain’s waste clearance system involves water exchange between brain tissue and CSF in perivascular spaces, which are part of the subarachnoid space (SAS). In this work, we found CSF T1 and T2 in SAS were shorter than corresponding values in the frontal-horns of lateral ventricle, which have minimal exchange. Numerical simulations showed that a higher brain-CSF water exchange rate was associated with lower apparent relaxation time in SAS, providing a potential means to estimate brain-CSF water exchange rate in vivo.INTRODUCTION

The brain’s waste clearance system is essential for the brain’s homeostasis, and dysfunction of this system may underlie various diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease.1 Recent studies have suggested that waste clearance involves water exchange between brain tissue and CSF in perivascular spaces, which are part of the subarachnoid space (SAS).1,2 There has been a growing interest in developing non-invasive MRI techniques to assess the brain-CSF exchange.3-5 Since brain tissues have much shorter T1 and T2 than CSF, the brain-CSF exchange is expected to result in lower apparent relaxation times of CSF in SAS than in regions without active exchange. In this work, we measured CSF T1 and T2 in SAS, in reference to corresponding values in the frontal-horns of lateral ventricle, which have minimal exchange. We further performed simulations to link the SAS relaxation time to brain-CSF exchange rate.METHODS

In-vivo Experiments: Seven healthy adults (3F4M, age=24.3±3.1) were scanned on a 3T Siemens Prisma scanner. For CSF-specific (i.e., no tissue or blood contributions) T1 measurement, we used an adiabatic inversion recovery sequence with spin-echo echo-planar-imaging readout. Ultra-long TE=700ms was used to eliminate partial-volume contamination from brain tissues or blood. 10 TIs of 50,500,1100,1800,2600,3600,4900,6800,10000 and 15000ms were acquired with the following parameters: single-slice of thickness=5mm, field-of-view=218×218mm2, resolution=1.7×1.7mm2, 2 averages and duration=4.8min.The sequence for CSF T2 measurement was similar to that for T1, except that the inversion recovery module was replaced with T2-preparation (T2-prep). Five effective-TEs (eTEs) of T2-prep: 0,640,1280,1960 and 2560ms were acquired with 2 averages and duration=2min. To examine whether the spacing between refocusing pulses in T2-prep (τCPMG) affected measured T2, we tested four τCPMG: 20,40,80, and 160ms.

To evaluate the reproducibility, each subject underwent three T1 mapping scans and three T2 mapping scans with each τCPMG.

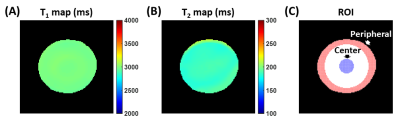

Phantom Experiments: An agarose gel (concentration=0.6%) phantom was scanned using the T1 and T2 mapping sequences, to examine whether they had spatially dependent biases in T1 or T2 measurement.

Simulation: To investigate the dependence of apparent SAS T1 on the brain-CSF exchange rate (k, in unit of min-1), we simulated the magnetization of CSF spins in SAS using modified Bloch equations:

$$\frac{dM_{z,c1}}{dt}=\frac{M_{0,c1}-M_{z,c1}}{T_{1,c1}}+k({\lambda}M_{z,c2}-M_{z,c1})$$

$$\frac{dM_{z,c2}}{dt}=\frac{M_{0,c2}-M_{z,c2}}{T_{1,c2}}+k(\frac{M_{z,c1}}{\lambda}-M_{z,c2})$$

where the subscripts “c1” and “c2” denote the tissue and SAS compartments, respectively. We assumed tissue T1,c1=1209ms.6 The CSF T1,c2 used the mean T1 in the frontal-horns of lateral ventricle measured in in-vivo experiments. λ is the brain/CSF partition coefficient assumed to be 0.8.7 The apparent T1 in SAS was then fitted using the simulated Mz,c2 values for k ranging from 0 to 1.6min-1.

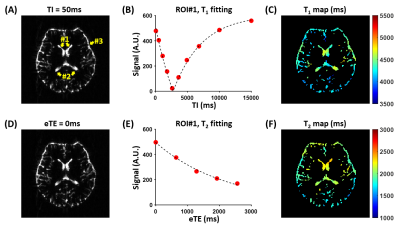

Data Processing: Voxel-wise T1 and T2 maps were computed for each scan. For quantitative analyses, T1 and T2 values of three regions-of-interest (ROIs) were calculated: ROI1 and ROI2 encompassed the frontal-horns and occipital-horns of lateral ventricle, respectively; ROI3 included all voxels in the SAS (Figure 1A). The coefficient-of-variation (CoV) of the ROI T1 and T2 values across the three scans were also computed.

Statistical Analysis: Paired t-tests with Bonferroni correction were used to compare the T1 values among the three ROIs. For T2, two-way repeated-measures analysis-of-variance (ANOVA) was used to examine whether the T2 values differ among ROIs or τCPMG values.

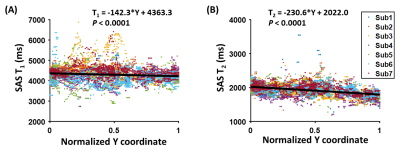

We also evaluated the spatial dependence of SAS T1 using linear-mixed-effect (LME) analysis. The dependent variable was the T1 value of a voxel, and the independent variable was the normalized anterior-posterior (Y) coordinate of the voxel (0=anteriormost, 1=posteriormost). This analysis was repeated for SAS T2 with τCPMG=20ms.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

In vivo Experiments: Figure 1 shows representative in-vivo data. Table 1 summarizes the ROI T1 and T2 values, as well as the CoVs. We found that the frontal-horns of lateral ventricle had higher T1 than SAS (raw P=0.006, Bonferroni-adjusted P=0.019), while the T1 in the occipital-horns was not different from the other two ROIs (P>0.2). For T2, ANOVA revealed significant effects of both ROI (P<0.0001) and τCPMG (P<0.0001). The frontal-horns had higher T2 than the occipital-horns (P=0.03) and SAS (P<0.0001). T2 values measured with τCPMG=20ms were larger than those measured with τCPMG=80ms or 160ms (P<0.05).Moreover, we found that there was a decrease from the frontal SAS to the occipital SAS in both T1 (P<0.0001, Figure 2A) and T2 (P<0.0001, Figure 2B).

Phantom Experiments: The phantom T1 and T2 maps were relatively uniform (Figure 3). For quantitative comparisons, we computed the T1 and T2 values in the center and peripheral regions of the phantom (Figure 3C), and found them to have negligible differences (center T1=2985.7ms vs. peripheral T1=2979.5ms; center T2=188.5ms vs. peripheral T2=188.8ms). This suggests that the regional differences in T1 and T2 observed in in-vivo experiments were not attributable to scanner effects such as B1 inhomogeneity.

Simulation: As illustrated in Figure 4, a higher exchange rate was associated with a lower apparent T1 in SAS. The average SAS apparent T1 of 4308.7ms measured in in-vivo experiments corresponded to an exchange rate of k=0.94min-1. When dividing the SAS along the anterior-posterior axis, the posterior SAS has a shorter T1 of 4221.0ms and a higher k=1.55min-1.

CONCLUSION

We observed that CSF in SAS had lower apparent T1 and T2 than the frontal-horns of lateral ventricle, providing a potential means to estimate brain-CSF water exchange rate in vivo.Acknowledgements

No acknowledgement found.References

1. Tarasoff-Conway JM, Carare RO, Osorio RS et al. Clearance systems in the brain-implications for Alzheimer disease. Nat Rev Neurol 2015;11:457-470.

2. Rasmussen MK, Mestre H, Nedergaard M. The glymphatic pathway in neurological disorders. Lancet Neurol 2018;17:1016-1024.

3. Petitclerc L, Hirschler L, Wells JA, Thomas DL, van Walderveen MAA, van Buchem MA, van Osch MJP. Ultra-long-TE arterial spin labeling reveals rapid and brain-wide blood-to-CSF water transport in humans. Neuroimage 2021;245:118755.

4. Li AM, Xu J. Cerebrospinal fluid-tissue exchange revealed by phase alternate labeling with null recovery MRI. Magn Reson Med 2022;87:1207-1217.

5. Evans PG, Sokolska M, Alves A et al. Non-Invasive MRI of Blood-Cerebrospinal Fluid Barrier Function. Nat Commun 2020;11:2081.

6. Lu H, Nagae-Poetscher LM, Golay X, Lin D, Pomper M, van Zijl PC. Routine clinical brain MRI sequences for use at 3.0 Tesla. J Magn Reson Imaging 2005;22:13-22.

7. Weiskopf N, Suckling J, Williams G, Correia MM, Inkster B, Tait R, Ooi C, Bullmore ET, Lutti A. Quantitative multi-parameter mapping of R1, PD(*), MT, and R2(*) at 3T: a multi-center validation. Front Neurosci 2013;7:95.

Figures