1460

Cerebrospinal fluid pathways are perturbed in aging and prodromal Alzheimer’s disease1Experimental medical science, Lund University, Lund, Sweden, 2Wallenberg Centre for Molecular Medicine, Lund University, Lund, Sweden, 3Clinical Memory Research Unit, Department of Clinical Sciences Malmö, Lund University, Malmö, Sweden, 4Skåne University Hospital, Department of Clinical Sciences Lund, Diagnostic Radiology, Lund University, Lund, Sweden, 5Lund University Bioimaging Center, Lund University, Lund, Sweden, 6Neuropsychiatric Clinic, Malmö University Hospital, Malmö, Sweden

Synopsis

Keywords: Neurofluids, Velocity & Flow

Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) circulation through the parenchyma by the glymphatic system has been suggested to play a role in the clearance of metabolic waste from the brain, including Amyloid β. In this 7T MRI study of CSF flow in the cerebral aqueduct, we find that ageing, cognitive status and amyloid status influence CSF dynamics and morphology of the aqueduct. These changes appear to precede major cognitive changes in Alzheimer’s disease. Disruption of flow dynamics and anatomy of CSF flow pathways may reflect dysfunctional CSF circulation in downstream compartments of the glymphatic system, and contribute to amyloid accumulation in the brain.

Introduction

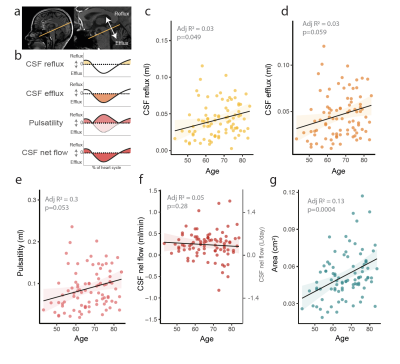

Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) circulation through the parenchyma via the pathways of the glymphatic system has been indicated to play a role in the clearance of waste products in the brain, including Amyloid β1. The amyloid hypothesis suggests that Amyloid β (Aβ) acts as the key culprit behind Alzheimer’s disease (AD) pathology. Although this hypothesis has received critique in recent years, current research suggests Amyloid β has value as a biomarker for early detection of AD2, and can even be targeted during early stages of the disease with clinically favourable outcomes3. Previous literature has described changes in CSF flow dynamics during the progression of AD. In this study, we examine the effects of ageing (Fig 1a-g), Amyloid β status (Fig 2a-e) and cognition (Fig 2f, fig 3a-i) on CSF flow dynamics and pathways using ultra-high field 7 Tesla MRI.Methods

92 participants (mean age 67, SD 9.8) from the Biofinder2 cohort4 were included in the study. 29 participants had mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and 63 subjective cognitive decline (SCD). 5 examinations were excluded due to poor MRI scan quality. The participant’s cognitive state was assessed by mini mental state examination (MMSE). CSF and blood samples were used for determining participants’ Amyloid β status. MRI scans were performed using a 7T MRI scanner (Achieva, Philips Healthcare, Best, the Netherlands) with a 2-channel transmit, 32-channel receive head coil (Nova Medical, Wilmington, MA, USA). Cardiac triggered through-plane phase contrast (2D-PC) was used to measure CSF flow in the cerebral aqueduct5 (Fig 1-4). The 2D-PC of the aqueduct was scanned at resolution of 0.3x0.3 mm2, 5 mm slice thickness and 15cm/s VENC. Flow data were analysed using Segment v2.2 R7052 (http://segment.heiberg.se).Volumetric analysis was done with Freesurfer (http://surfer.nmr.mgh.harvard.edu/). Prism (GraphPad) and R were used for statistical analysis. Results from linear regression adjusted for age and sex are presented as p values for each regression (lm).Results

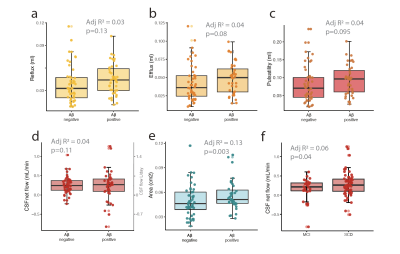

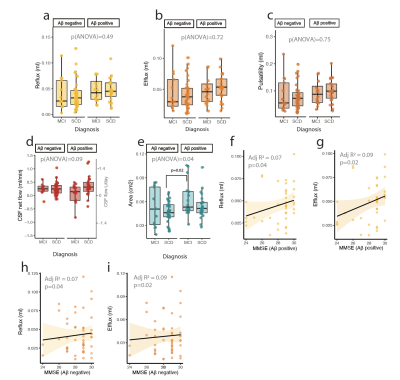

We find that the cerebral aqueduct cross-sectional diameter increases with age (p(lm)=0.004). Additionally, CSF efflux in the aqueduct (flow in cranial direction towards the 3rd ventricle) is significantly increased (Fig 1c, p(lm ~age, sex)= 0.049). A trend towards increased efflux volume (Fig 1d, p(lm ~age, sex)=0.059) and CSF pulsations (Fig 1e, p(lm ~age, sex)=0.053) was also observed. CSF net flow was not affected. The enlargement of the cerebral aqueduct was increased in Amyloid β positive subjects (Fig 2e, p(lm ~age, sex)=0.003), but this change in the morphology was not reflected in clear changes in CSF flow dynamics, although there was a non-significant tendency for more CSF oscillations in Amyloid β positive subjects(Fig 2a-c).In mild cognitive impairment, CSF net flow was significantly reduced (Fig 2f, p(lm ~age, sex)=0.04). When splitting the data by Amyloid β as well as cognitive status (Fig 3a-e), aqueduct cross-sectional area increased in Aβ positive MCI patients in particular (3e). Additionally, there was a tendency to increased CSF flow oscillations in the Aβ positive patients with subjective cognitive decline although this was not significant (Fig 3a-c). To study this effect further we examined the relationship of cognitive performance and CSF flow dynamics. The reflux and efflux volumes in Aβpositive patients correlated with MMSE score (Fig 3f-g). This effect was not seen in Aβ negative subjects (Fig 3h-i).

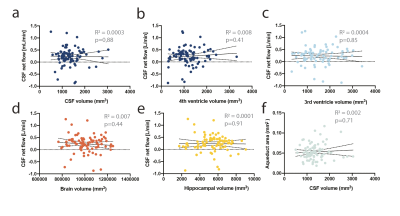

To determine whether changes in aqueduct size or CSF dynamics correlated with general atrophy, we performed volumetric analysis of the brain and the ventricular system (Fig 4a-f) but found no significant correlations.

Discussion

Our study finds altered CSF flow dynamics in aging. Increased CSF oscillations in cranial and caudal directions have been reported when comparing elderly to young (under 50 years) participants5. Even various aspects of cognition have been linked to altered CSF flow dynamics, suggesting CSF net flow is decreased with impaired cognition6, similar to our findings. Similar to our findings, hyperdynamic CSF stroke volumes have been reported in MCI, although the difference to healthy ageing is not statistically significant7. However, the data on the relationship between cognition and CSF flow is somewhat inconclusive.To our knowledge, changes in aqueduct morphology have not previously been reported in healthy ageing or prodromal AD. We find positive amyloid β status is correlated with aqueductal enlargement. The enlargement of the aqueduct appears to precede the cognitive changes, and does not reflect a high degree of general atrophy (Fig 4). This may suggest aqueduct morphology reflects early disturbances in CSF flow pathways, that may result in defective CSF circulation, and potentially affect CSF mediated brain clearance.

Conclusion

In this 7T MRI study of CSF flow in the cerebral aqueduct, we find that aging, cognitive status and Amyloid status influence CSF flow dynamics and aqueduct morphology. Our findings support existing data that CSF flow dysfunction happen early in AD progression and likely precede notable cognitive changes. Early occurrence of CSF flow disturbances may suggest that they contribute to the disease pathogenesis and accumulation of Amyloid β plaques. Further studies are needed to address whether maintenance of CSF flow homeostasis could help hinder plaque build-up and slow down disease progression.Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the National 7T facility in Lund, Sweden for their support. Thank you to Knut and Alice Wallenberg foundation and Osk Huttunen säätiö for funding.References

1. Iliff JJ, Wang M, Liao Y, et al. A paravascular pathway facilitates CSF flow through the brain parenchyma and the clearance of interstitial solutes, including amyloid β. Sci Transl Med. 2012;4(147):147ra111. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.3003748

2. Hansson O, Lehmann S, Otto M, Zetterberg H, Lewczuk P. Advantages and disadvantages of the use of the CSF Amyloid β (Aβ) 42/40 ratio in the diagnosis of Alzheimer's Disease. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2019;11(1):34. Published 2019 Apr 22. doi:10.1186/s13195-019-0485-0

3. Tagliapietra M. Aducanumab for the treatment of Alzheimer's disease. Drugs Today (Barc). 2022;58(10):465-477. doi:10.1358/dot.2022.58.10.3422314

4. The Swedish BioFINDER 2 Study. ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03174938.

5. Markenroth Bloch K, Töger J, Ståhlberg F. Investigation of cerebrospinal fluid flow in the cerebral aqueduct using high-resolution phase contrast measurements at 7T MRI. Acta Radiol. 2018;59(8):988-996. doi:10.1177/0284185117740762

6. Sartoretti T, Wyss M, Sartoretti E, et al. Sex and Age Dependencies of Aqueductal Cerebrospinal Fluid Dynamics Parameters in Healthy Subjects. Front Aging Neurosci. 2019;11:199. Published 2019 Aug 2. doi:10.3389/fnagi.2019.00199

7. Attier-Zmudka J, Sérot JM, Valluy J, et al. Decreased Cerebrospinal Fluid Flow Is Associated With Cognitive Deficit in Elderly Patients. Front Aging Neurosci. 2019;11:87. Published 2019 Apr 30. doi:10.3389/fnagi.2019.00087

8. El Sankari S, Gondry-Jouet C, Fichten A, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid and blood flow in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer's disease: a differential diagnosis from idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus. Fluids Barriers CNS. 2011;8(1):12. Published 2011 Feb 17. doi:10.1186/2045-8118-8-12

Figures

Figure 1: CSF flow is affected by ageing. a) 2D-PC scan plane is placed perpendicular to the cerebral aqueduct. b) CSF flow in the aqueduct is pulsatile, with a cranial reflux and caudal efflux component. Pulsatility is the absolute sum of efflux and reflux. c) CSF reflux towards the cranium is increased with ageing. d) There is a tendency for increased CSF efflux and e) pulsatility. f) CSF net flow (positive flow=CSF efflux) is unaffected by aging. g) Aqueductal area is increased by aging. Statistical analysis c-g linear regression adjusted for age and sex.

Figure 2: CSF pathways are perturbed in Amyloid β positive patients. a) CSF reflux (cranial stroke volume) b) efflux (caudal stroke volume) and c) pulsatility (reflux + efflux) show a nonsignificant tendency to higher flow in amyloid positive subjects. d) CSF net flow shows a higher variation and a non-significant increase in amyloid positive subjects. e) Cerebral aqueduct is enlarged in Amyloid β positive subjects. f) CSF net flow is reduced in MCI. Statistical analysis a-f linear regression adjusted for age and sex.

Figure 3: Cognitive performance is connected to changes in CSF flow. There were no significant differences in a) CSF reflux b) efflux, or c) pulsatility, but a tendency for increase in amyloid positive SCD group. d) CSF net flow showed a non-significant tendency for reduced flow in amyloid positive MCI. e) Aqueduct cross sectional area was increased in amyloid positive MCI patients. f) CSF reflux and g) efflux stroke volumes correlate with MMSE performance in amyloid positive, but not amyloid negative subjects. h) Reflux and i) efflux in amyloid negative subjects.

Figure 4: CSF flow does not correlate with brain or CSF volume. a) CSF volume or the volume in b) 4th or c) 3rdventricle does not correlate with aqueductal CSF flow. d) Total brain volume or e) hippocampal volume do not correlate with CSF flow. f) CSF volume does not correlate with aqueductal cross sectional area. Stastistical analysis a-f simple linear regression.