1459

Physical exercise activates intrinsic CSF outflow metrics in healthy humans

Mitsue Miyazaki1, Vadim Malis1, Asako Yamamoto2, Jirach Kungsamutr3, Marin McDonald1, Linda McEvoy1, and Won Bae1,4

1Radiology, University of California, San Diego, La Jolla, CA, United States, 2Radiology, Teikyo University, Tokyo, Japan, 3Bioengineer, University of California, San Diego, La Jolla, CA, United States, 4VA San Diego Healthcare System, San Diego, CA, United States

1Radiology, University of California, San Diego, La Jolla, CA, United States, 2Radiology, Teikyo University, Tokyo, Japan, 3Bioengineer, University of California, San Diego, La Jolla, CA, United States, 4VA San Diego Healthcare System, San Diego, CA, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Neurofluids, Neurofluids, CSF, glymphatic egress pathways, active and sedentary

Possible two intrinsic CSF egress pathways of dura mater and the lower parasagittal dura (PSD) are observed using non-contrast spin-labeling MRI. Intrinsic CSF outflow metrics increase in the adults with an active lifestyle than adults with sedentary lifestyle. However, after 3 weeks of increased physical activity, the sedentary group showed improved CSF outflow metrics. This improvement was notable at the lower PSD, where outflow metrics were highest among the active group. These quantitative CSF results indicate a new pathway of CSF flow from the lower PSD to the superior sagittal sinus that is most evident in physically active individuals.Introduction

Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) clearance is essential for maintaining a healthy brain and cognition by removal of metabolic waste. Physical exercise has been known to improve human health; however, the effect of physical exercise on intrinsic CSF outflow pathway and their quantitative metrics in humans remains unexplored. The aim of the present study was to investigate intrinsic CSF outflow pathways and their quantitative metrics using our newly developed spin-labeling MRI technique1 among healthy adults with active lifestyles and those with more sedentary lifestyles. We also examined differences in intrinsic CSF outflow metrics among sedentary adults after they increased their physical activity levels for three weeks. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) clearance is essential for maintaining a healthy brain and cognition by removal of metabolic waste. Physical exercise has been known to improve human health; however, the effect of physical exercise on intrinsic CSF outflow pathway and their quantitative metrics in humans remains unexplored. The aim of the present study was to investigate intrinsic CSF outflow pathways and their quantitative metrics using our newly developed spin-labeling MRI technique1 among healthy adults with active lifestyles and those with more sedentary lifestyles. We also examined changes in the CSF outflow metrics in sedentary adults after they increased their physical activity levels for three weeks.Methods

This study was performed on 18 healthy adults with informed consent, using a clinical 3-Tesla MRI scanner. We classified participants into two groups based on reported time spent sitting per day (active group < 7 hours or an average of 5.3 ± 0.7 sitting per day and sedentary group ≥ 7 hours or an average of 10.4 ± 1.7 sitting per day). To elucidate the effect of exercise, the sedentary individuals were asked to increase their activity to at least about 3.5 hours per week for 3 weeks. All participants were administered the International Physical Activity Questionnaire - short form (IPAQ-SF)2. To elucidate intrinsic CSF outflow pathways and quantitative metrics, we studied both image subtraction and signal increase ratio (SIR) of time-resolved images at various inversion times (TI). Figure 1 shows our proposed intrinsic CSF egress pathways of 1) dura mater to superior sagittal sinus (SSS), via parasagittal dura (PSD), and 2) the lower PSD pathway. Administration of intrathecal3 and intravenous4 gadolinium-based contrast agent (GABC) shows 24-48 hours of retention of GABC and dural lymphatic vessels, respectively. We also measured quantitative outflow metrics at 5 segmented region-of-interests (ROIs); upper PSD, middle PSD, lower PSD, SSS, and entire SSS. All MRI examinations were performed on a clinical 3-T MRI scanner (Vantage Galan 3T, Canon Medical Systems Corp., Japan), equipped with a 32-ch head coil.Results

The average physical activity length of the active lifestyle group was 7.0 ± 3.8 hours. The sedentary before and after physical activity length was 1.2 ± 1.9 and 6.1± 2.7 hours, respectively. Figure 2 shows an example of the tag-on, tag-off, subtraction and SIR color images. The adults with an active lifestyle show outflow signals in the subtraction images, whereas the sedentary lifestyle shows less outflow signals (Figure 3). However, the sedentary post-exercise shows increased outflow signals (Figure 3C). Figure 4 shows the intrinsic CSF outflow images and quantitative metrics of the sedentary individual pre- and post-exercise. Figure 5 shows the 5 ROI segmentations and quantitative metrics of the active, pre-exercise sedentary, and post-exercise sedentary groups. The active lifestyle group shows greater intrinsic CSF outflow metrics in peak height (PH), relative CSF volume (rCFV), and relative CSF flow (rCFF) (p < 0.05) than adults with sedentary lifestyle (Figure 5B). However, after 3 weeks of increased physical activity, the sedentary group showed improved CSF outflow metrics (Figure 5B, green to blue). This improvement was notable at the lower parasagittal dura (PSD), where outflow metrics were highest among the active group and after exercise in sedentary group (i.e., Figure 3A and C). These quantitative CSF results indicate a new pathway of CSF outflow from the lower PSD to the SSS that is most evident in physically active individuals.Discussion

This is the first study to show the effect of exercise on CSF outflow pathways of upper PSD to SSS and the lower PSD to SSS utilizing noninvasive non-contrast MRI techniques in humans, and to demonstrate a spatially selective, durable increase in CSF outflow via the lower PSD. Naganawa et al.5 have observed rapid GABC enhancement in the space filled with perivascular fluid between the pia sheath and the cortical venous wall, which drains into the inferior aspect of the SSS, using a 3D-real inversion recovery technique5. We also observed the tagged CSF signals around the subpial space. Studies report that the perivascular space (PVS) between two leptomeningeal membranes in the basal arterioles and venioles directly communicate with the SAS, whereas the PVS in cortical arterioles and venioles have a single leptomeningeal membrane which communicates with the subpial space. Our subtraction images (Figure 2) clearly show intrinsic CSF signals around the subpial space6,7.Conclusions

Our findings show that physical exercise drives CSF outflow metrics with a greater degree in the lower PSD pathway, which may be responsible from the perivascular space of cortical veins or subpial space.Acknowledgements

This work was supported by an NIH grant RF1AG076692 (MM) and a grant by Canon Medical Systems, Japan (35938).References

1] Malis V, Bae WC, Yamamoto A, McEvoy LK, McDonald MA, Miyazaki M. in press Magn Reson Med Science.

2] Craig CL, Marshall AL, Sjostrom M, et al. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise 2003; 35(8):1381–95. 3] Ringstad G, and Eide PK. Nature Communications 2020;11:354.

4] Absinta M, Ha SK, Nair G, et al. eLife 2017;6:e29738.

5] Naganawa S, Ito R, Taoka T, Yoshida T, Sone M. Magn Reson Med Sci. 2020; 10:19(1):1-4.

6] Pollock H, Hutchings M, Weller RO, Zhang E-T. J. Anat. 1997;191 337-346.

7] Wardlaw JM, et al. Nat Rev Neurol 2020; 16(3), 137-153.

Figures

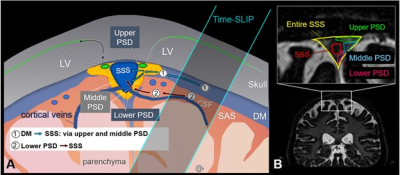

Fig. 1. Drawing of

intrinsic CSF egress pathways, we observed using non-contrast MRI. (1) Dura

mater pathway: dura mater to upper PSD and/or middle PSD, and then to SSS. (2)

Lower PSD pathway: Lower PSD to SSS, a possibility of the subpial space or

perivascular space of cortical veins. Note that dural lymphatic vessels are

observed by Gd-tracer studies, not visualized by non-contrast MRI. B) Coronal

image and the enlargement with segmentations showing the upper PSD (green), middle

PSD (blue), lower PSD (pink), SSS (red), and entire SSS (yellow).

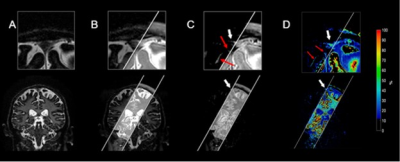

Fig. 2. Coronal spin-labeling A) tag-off, B) tag-on, C) subtraction image of tag-off from tag-on with an absolute value, and D) signal Increase ratio (SIR) calculated by |tag-off – tag-on|/|tag-off|. White parallel lines show the location of the oblique Time-SLIP tag pulse. Note that CSF signals outside of the tag pulse have moved out from the tagged region and are seen at PSD and lower PSD in enlarged C) and D), as shown by white arrows. In addition, tagged CSF signals can be seen in the subpial space (red arrows). PSD: parasagittal dura, SSS: superior sagittal sinus.

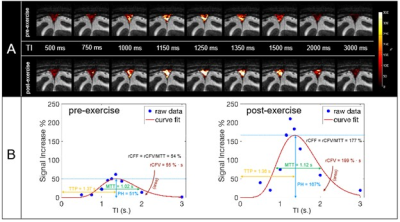

Fig. 3. Simple tag-on and tag-off subtracted images of an

active lifestyle participant (A), and a sedentary participant before (B)

and after increase in physical activity for 3 weeks (C). Enlarged

image of (A) clearly shows tagged CSF moving out from the left-brain

hemisphere to the upper PSD (red arrow) and to the lower PSD (orange arrow). The

sedentary individual, the enlarged (B) image, shows small signals

of tagged CSF; however, (C) after exercise clearly shows tagged CSF at

the upper PSD (red arrow), the lower PSD (orange arrow), and around the SSS

(white arrows).

Fig. 4. A) Fusion images of signal increase ratio (SIR) over

tag-off image before and after exercise. Note brighter or higher SIR values are

seen in post-exercise. B) SIR plots of actual measured data (blue) and curve

fitting (orange). Circles (blue) show the measured data points, and the

orange line indicates the curve fit. Quantitative measures of (Left) before and

(Right) after exercise. Note

that MTT and TTP are similar, and no notable changes are observed pre- or post-

exercise.

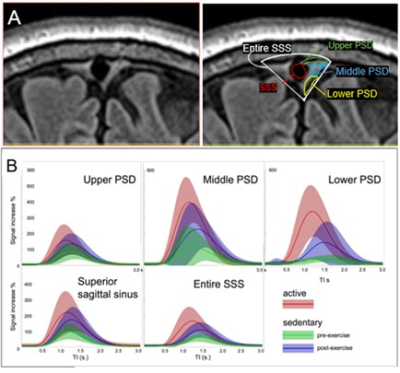

Fig. 5. A) Segmentation of meninges region over the FLAIR image. Segmentations were drawn in 5 ROIs, upper PSD, middle PSD, lower PSD, SSS, and entire SSS. B) CSF outflow curves of active adults, sedentary adults, and sedentary adults after three weeks of physical exercise at the above 5 ROIs. Note that the active adults show high quantitative metrics in all regions. The sedentary adults show lower quantitative measures; however, after 3 weeks of increased physical activity there is substantial improvement in all regions, especially at the lower PSD.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.58530/2023/1459